A new archive is finally giving everyday Black women the reverence they deserve

A daughter’s quest to honor her mother’s legacy brought her to the question: “Whose account of the past counts?”

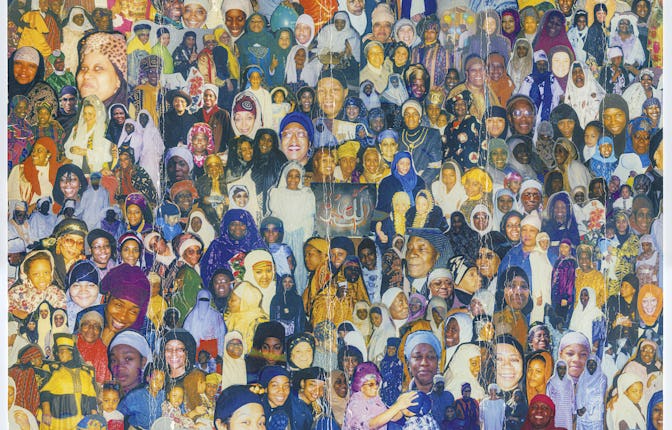

Throughout Black History Month, the same names are often invoked as leaders or visionaries to remember — men like Malcolm X, Martin Luther King Jr., Huey Newton, and W.E.B. Du Bois. In some ways, they transcend time and space as people eagerly search for past figures to learn from. But unless you’re a Black Muslim from New York City, the name Amina Amatul Haqq may not ring a bell. It means everything to her daughter, Dr. Su’ad Abdul Khabeer, though — and through her latest project, Umi’s Archive, Abdul Khabeer wants to show that the lives of everyday Black women like her mother deserve reverence.

A lifelong New Yorker, Amatul Haqq was born in Harlem as Audrey Beatrice Weeks on April 4, 1950, and passed away in October 2017 in Queens. While Amatul Haqq would eventually become a public school teacher, she was also an accomplished pianist and drama student. In 1963, she auditioned at Carnegie Hall for membership in the National Fraternity of Student Musicians and, that next year, become a member of the National Piano Playing Auditions.

“She lived a really kind of remarkable life,” Abdul Khabeer, a cultural anthropologist and author of Muslim Cool: Race, Religion, and Hip Hop in the United States, tells Mic. As a lifelong activist, including becoming a member of the Black Panthers and co-founding the Northeast Muslim Women’s Alliance, Amatul Haqq was well-known in her communities — so much so that in 2008, Sept. 16 was commemorated as “Sister Amina Amatul Haqq Day” in Queens for her work “promoting women’s rights, social justice, and racial harmony.”

Following her mother’s passing, Abdul Khabeer was left with Amatul Haqq’s archive, a wealth of familial collections as well as her mother’s own personal treasures. There were thousands of items, ranging from marriage certificates to diary entries to letters Amatul Haqq exchanged with incarcerated people in Ohio. There were photos from Amatul Haqq’s childhood in New York City, where the lack of a single white person in the images revealed that from an early age she lived in a Black world.

Abdul Khabeer realized, “Other people need to see this stuff.”

“[My mother is] not like Angela Davis,” Abdul Khabeer says. “She’s not a household name in that way. But her life and the things she did in the communities she was a part of — the things they built — are full of knowledge that will help us.”

That’s why Abdul Khabeer launched Umi’s Archive, a digital six-part exhibition series, in 2021. The title may already be familiar to hip-hop heads thanks to Mos Def’s 1999 “Umi Says” — but if you’re not in the know, “umi” is an Arabic word that directly translates to “my mother.” However, Abdul Khabeer tells Mic, “It’s probably like the English equivalent — or I call it Black Arabic — of ‘mommy.’”

The items that Abdul Khabeer digitized didn’t only come from Amatul Haqq, either. Many of the early photographs were taken by Abdul Khabeer’s grandfather, for whom photography was a preferred method of documenting his life.

“I think that awareness of what it means to be Black and not have your stories being documented or maintained was a kind of undercurrent in her family,” Abdul Khabeer tells Mic. “[My grandfather] has upwards of 500 photos from his time in World War II. The photos have dates, names, [and] locations on them. They were in photo albums. He has photos from when he was a teenager and of family members. He clearly understood the significance of saving and documenting things.”

As an academic scholar and cultural anthropologist, Abdul Khabeer says she’s trained to work alone. But with thousands of artifacts on hand, Abdul Khabeer realized she couldn’t properly care for the trove by herself. So she assembled a team to help with digitizing, transcribing, and developing a website to preserve everything.

“I’ve pulled [Umi’s Archive] together as a reclaimed space where we can remember and dream,” Abdul Khabeer tells Mic. “My mother was part of a generation that did a lot of things. There’s still a lot that we need to learn from them as we are present and in positions to make change in the world. We can learn from, think, and dream about what we want to see based on what they did.”

Family portrait of Amatul Haqq with her mother and first child, Su’ad Abdul Khabeer. 1978.

Politically speaking, Umi’s Archive comes at an interesting time. “In the university world, there’s this whole campaign ‘cite Black women,’” Abdul Khabeer explains. Started by Christen A. Smith in 2017, the campaign pushes people to acknowledge “Black women’s transnational intellectual production.” Outside of academia, Abdul Khabeer says, “there’s this other conversation, especially after Trump was elected: ‘Listen to Black women.’”

That general message — that Black women know things of importance and that these things are being lost — frames Umi’s Archive. On the website itself, the archive opens with two questions: “Whose account of the past counts? Whose lives should be remembered?”

Abdul Khabeer isn’t new to archives or digital spaces. She’s the founder of Sapelo Square, an online publication about Black Muslims in the United States. With Umi’s Archive, though, she wanted to push back at the notion that only the most exceptional people are worthy of remembrance. Or, to be more blunt, that “only some people are actually people. And ... only certain types of people have power. If you’re a human being who doesn’t fall into those categories, you don’t count. Your account of the past ... is not considered authoritative [or] legitimate.”

The exclusion of those who are not considered powerful or extraordinary leads to incomplete versions of history. How much do you know about yourself, your communities, and the world if you’re only looking at the lives of a selected few? “That’s the way white supremacist power works,” Abdul Khabeer continues. “You have to challenge that by not leaving things out.”

Amatul Haqq in Columbus Ohio in 1969.

Abdul Khabeer says her deep connection with her mother helped her decide what to include in the archive. For example, she included handwritten notes and recordings of Amatul Haqq’s time taking Islamic classes at 72nd Street, because through these artifacts she saw how in Islamic spaces, Black women, who faced misogynoir in the everyday world, found safety and security that allowed them to continue working in the Black radical tradition.

“My mother and her cohort would not refer to themselves as feminist. But I would call them that. They were contemporaries of the Black feminist movement that we think about today,” Abdul Khabeer says. “All of them have a Black radical past before they become Muslim.” To those women, Islam became a “place where they can continue to challenge and build things.”

Even where Black radical traditions are not explicitly named, they are evident throughout Umi’s Archive. Amatul Haqq’s own collecting process was likely driven by her political consciousness. As an educator and activist, Amatul Haqq knew the importance of sharing information, and so she often had doubles of things. Her daughter explains: “She gets a book, she gets two ... because the point is you’re going to share it with somebody. This is good information, I need to share it, so I’m gonna get more than one.”

While an archive is inherently concerned with the past, Umi’s Archive is not meant to be contained there. By sharing Amatul Haqq’s history, she can continue to shape the world, just as she did while on this earth. Abdul Khabeer tells Mic, “Now we know this story. Now we know this struggle. How does that new information help us with what we’re dealing with right now? That’s the next step this project is hoping to inspire.”

Umi’s Archive has already translated to direct action. While she was always aware of her mother’s abolitionist work, Abdul Khabeer discovered how deep it went during her archival process. She learned that in college, Amatul Haqq would work with her then-boyfriend to register people recently freed from prison as students at Ohio State University. She also regularly corresponded with incarcerated people.

“One of the things we did during the exhibition was have a letter writing session,” Abdul Khabeer tells Mic. For it, participants wrote letters for Imam Jamil Al-Amin, a Black activist convicted of killing a deputy sheriff in a highly controversial trial. “We talked about [Al-Amin’s] case and encouraged people to write letters in support, because he was not able to receive letters directly.”

With all of the elders in Abdul Khabeer’s family living as ancestors now, Umi’s Archive is in some ways a death cleaning process. But through it, Abdul Khabeer asserts a popular Black Muslim refrain: knowledge of self.

“Everything has something. We all have this collective story and a collective power,” Abdul Khabeer says. “Your belief in your power depends on your knowledge about who you are.”

She adds: “This listening and storytelling is furthering our fight for liberation.”