A New Study May Finally Put Doubts About Campus Sexual Assault to Rest

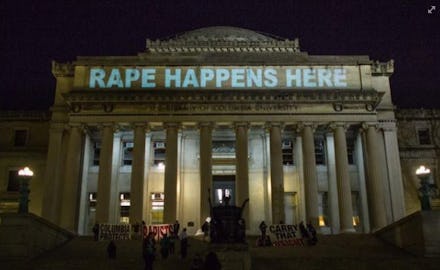

Sexual assault, especially on college campuses, is an indisputably complex and horrifying phenomenon that can be difficult to quantify. In fact, one study — that 1 in 5 women will experience attempted or completed rape while at college — is constantly invoked, possibly because there are so few other figures available.

That statistic, however, has been widely disputed. But to raise awareness and generate action, activists need figures to back up their arguments. While the old 1 in 5 statistic may be too shaky, it appears a new study may provide a little more concrete proof.

The disputed figure: The original statistic, which has been cited by campaigns and politicians, can be traced to a 2007 study conducted for the Justice Department. The participants were 5,446 undergraduate women from two large public universities. The survey was Web-based, with a low response rate, and only included freshmen, sophomores and juniors, according to the Washington Post.

While this study may actually suggest sexual assault rates are lower than commonly cited, such studies fail to recognize the fact that sexual assault is one of the most underreported crimes, and the actual rate is likely higher. For example, another National Institute of Justice study found only 26% of sexual assaults were reported between 1992 and 2000.

Additionally, social factors aren't accounted for in such surveys, such as respondents' misunderstanding of what constitutes sexual assault since people's understanding of consent varies. There is also the complex reality of trauma that plenty of survivors experience, which may deeply inform how they personally percieve their assault.

The new study: The Journal of Adolescent Health, however, recently released another study that ultimately bolsters the original rate. According to the study, an estimated 15.3% of freshman women reported an attempted or completed rape during their first year on campus. This number increased to 18.6% when researchers accounted for women who reported more than one event.

Though this study clearly differentiated between rape and other forms of sexual assault, and controlled for a specific year in college — which, as Joshua A. Krisch of Vocativ reported, results in a "rare, statistically sound snapshot of campus rape" — it is hardly flawless. It is based on self-reported data from a single class of students at a single college and only accounted for attacks that occurred while an individual was incapacitated.

That researchers are continuing to gather data on the topic is encouraging and highlights how necessary it is to implement interventions. As Kate Carey, lead and corresponding author of the study and professor of behavioral and social sciences in the Brown University School of Public Health, said, "If you swap in any other physically harmful and psychologically harmful event, a prevalence of 15% would be just unacceptably high."

Ultimately, this study shows that while anti-sexual assault activists can't hedge their claims on single, limited surveys, there also needs to be far more research about this issue. Flawed research in no way means that campus sexual assault isn't occurring. It is, and the more attention paid to the issue and research conducted about it, the sooner we'll come to comprehensively addressing it.