The NYPD Commissioner Accidentally Revealed a Big Problem With the Criminal Justice System

In light of the national debate over the frayed relationship between the police and African-American communities, police departments across the country have set about recruiting more non-white officers into their ranks. But at least in New York, there's an obstacle that lays bare the very problem that hiring more diverse officers would attempt to correct.

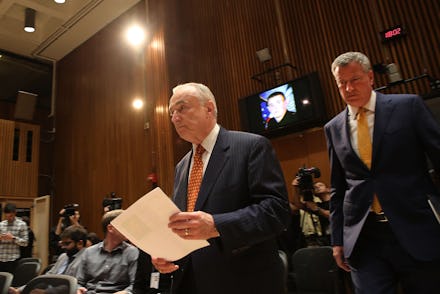

According to New York police Commissioner Bill Bratton, the reason that the New York Police Department doesn't have enough black officers is partially because too many potential candidates have a criminal record.

"We have a significant population gap among African-American males because so many of them have spent time in jail and, as such, we can't hire them," Bratton told the Guardian in an interview.

The NYPD application process automatically discounts former felons, and multiple convictions for smaller offenses that suggest "disrespect for the law" could also disqualify a candidate, according to the Guardian. In New York City, African-American men account for a disproportionately high rate of convictions, so the NYPD is constrained in its ability to hire a police force that reflects the population. But it's a predicament that was in part manufactured by Bratton himself.

Broken windows, deferred dreams: In the 1990s, under Mayor Rudy Giuliani, Bratton orchestrated an overhaul of the NYPD's policing strategy based on the controversial "broken windows" theory. Broken windows holds that constant and aggressive enforcement of low-level crimes is the best way to maintain order, and eventually leads to a decrease in more serious crimes.

Bratton also oversaw the expansion of stop-and-frisk tactics — systematically stopping people in public and patting them down — which were "a direct extension of the invasive broken windows policing tactics," Alex Vitale, an associate professor of sociology at Brooklyn College, told Mic. Later, under the tenure of New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg, police Commissioner Ray Kelly escalated Bratton's model further, adding the policing of "hot spots" to the mix.

The critical thing to know about the legacy of Bratton and Kelly is that their obsession with broken windows and stop-and-frisk meant very different things for different New Yorkers. Poor communities of color were monitored and policed with feverish intensity, and stop-and-frisks were employed prejudicially. According to the New York Civil Liberties Union, between 2002 and 2011, black and Latino residents made up nearly 90% of the millions of people stopped under stop-and-frisk. While an overwhelming amount of them were innocent, hundreds of thousands of minorities were pulled into the criminal justice system — often for nonviolent offenses like possession of drugs — by way of a policy that left white New Yorkers largely untouched. In 2013, the stop-and-frisk policy that Bratton cherished was struck down by a federal judge and deemed a form of racial profiling.

Bratton's legacy: The systematic stops have ended, but their consequences remain to this day. According to the Guardian, Bratton admitted as much:

Bratton blamed the "unfortunate consequences" of an explosion in "stop, question and frisk" incidents that caught many young men of color in the net by resulting in them being given a summons for a minor misdemeanor. As a result, Bratton said, the "population pool [of eligible non-white officers] is much smaller than it might ordinarily have been."

Bratton seems to have walked back those remarks. After his comments to the Guardian generated a good deal of outrage in the city, he subsequently slammed the Guardian article for taking his quotes out of context. According to the Daily News, Bratton told reporters that "it's an unfortunate fact that in the male black population, a very significant percentage of them, more so than whites or other minority candidates, because of convictions, prison records, are never going to be hired by a police department. That's a reality. That's not a byproduct of stop-and-frisk."

He's correct in saying that felony records among African-Americans makes it harder to recruit black police officers. But in doing so — and by denying that policies like stop-and-frisk had anything to do with the over-prosecution of black suspects — Bratton reveals the absurdity of the policies that he himself helped to create.