Woman Charged With False Reporting After Her Fitbit Contradicted Her Rape Claim

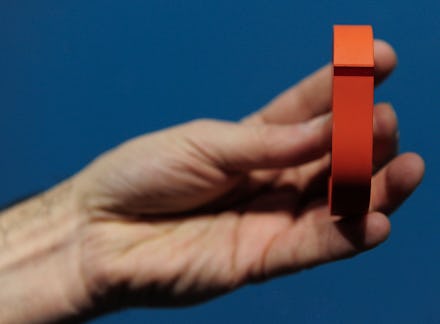

A woman in Saint Petersburg, Florida, has been charged with making false reports to law enforcement after her Fitbit — the wearable activity tracker that measures things like steps, sleep and calories — appeared to show inconsistencies in her claim that she had been sexually assaulted.

The 43-year-old, who was at her boss's home in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, at the time of the event she reported, told police "an unknown man pulled her out of bed, attacked her in a bathroom and raped her at knifepoint," ABC 27 News reported. However, her Fitbit, which she had said disappeared during the assault, was later found a few feet away from the bathroom.

Fitbits are traditionally used to track physical activity and wellness. They can also measure the number of hours the user has slept, as well as the quality of sleep.

According to the criminal complaint, the device showed the woman "had been awake and walking around the entire night, not sleeping as she had claimed," ABC 7 News reported. Police also said there were no footprints in the snow outside the house or any other signs of an intruder.

Along with the false reporting charge, ABC 7 News noted that the woman was charged with making false alarms to public safety and tampering with evidence.

False rape claims are less common than they seem. The Fitbit incident — the claims of which are still under investigation — is an easy target for inflammatory analysis. (The Daily Caller, for example, sarcastically headlined its piece about the incident, "If You're Going to Fake a Rape, Remember to Take Off Your Fitbit.")

But it's important to remember that false rape claims are rare. While they certainly exist, it's estimated that 2% to 8% of rape claims are later proven false, according to the National Sexual Violence Resource Center. That's about the same as the false reporting rate for other crimes, such as car theft or stalking.

Conservatives, men's rights activists and other anti-feminist groups often harp on false rape allegations to criticize national campaigns against sexual assault. "Is there really a rape epidemic? Probably not," the National Review wrote in 2014. Rolling Stone's now-discredited cover story detailing an alleged gang rape at the University of Virginia added more fuel to the fire. When Columbia University student Emma Sulkowicz rose to national prominence with her anti-rape performance art piece, "Carry That Weight," she was maligned publicly by posters in New York City calling her a "pretty little liar."

It's not productive to ignore all instances of false rape claims, but it's equally harmful to cast a suspicious eye to all accusations just because of a small minority. We don't do that for other crimes, and rape should be no different. Like with the UVA case, even if one woman's story is questioned, it's important that we believe survivors of rape and sexual assault.