Here's the Lesson 'Straight Outta Compton' Doesn't Want You to Learn

N.W.A casts a long shadow in Southern California.

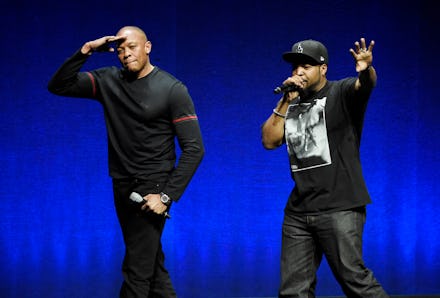

For Los Angeles kids born in the mid- to late '80s, exposure to the group's work came mostly through its musical descendants, a crew that orbited rapper-producer Dr. Dre's sphere of influence like planets: Snoop Dogg, Xzibit, Nate Dogg, the Game, arguably 50 Cent and Eminem, and, most recently, Kendrick Lamar and the Top Dawg Entertainment clique.

Their music was the soundtrack to our middle school dance parties. It crackled from our headphones during bus rides and lent ambiance to our musings at backyard barbecues. Most of us were still in diapers when the Straight Outta Compton album was released in 1988 — the year "Fuck tha Police" provoked the ire of the FBI and all but predicted the LA Uprising four years later.

But the artists who carried N.W.A's mantle for the next two decades left no question as to how definitively these young black men had shaped perceptions of our city — locally, globally, musically and otherwise — and of ourselves.

This is especially clear in the new N.W.A biopic, Straight Outta Compton, which comes out on Aug. 14. Dre's Chronic 2001 album remains a cornerstone of late-1990s adolescence, but many of us grew up knowing Ice Cube as the guy from Friday, Eazy-E as the dude who sang "Boyz-n-the-Hood," and we'd be hard pressed to find anyone who'd even heard of DJ Yella or MC Ren. For anyone not fully cognizant during the late 1980s, this movie is the first time we get to witness the entire group's origin story firsthand.

Watching this film, it's immediately clear that the debt California hip-hop owes N.W.A is beyond measure. The group's blunt, often celebratory narration of life on LA's margins pulsed with a nihilistic bravado that has since informed so much of the region's music, not to mention articulated some extreme forms of hyper-masculinity to which many of us, at our youthful worst, hoped to aspire.

There are also plenty of lessons to be learned.

Here's one: Compton in the late 1980s was hell in a way that much of poor, black Los Angeles was at the time. Gang-banging and drug dealing ruled the social order. Black bodies were being contained, molested and brutalized by a network of police departments whose predilection for plunder and militarized violence has rarely been matched since. The logic behind "Fuck tha Police" becomes exceedingly clear as the narrative unfolds. When the group is rousted by law enforcement in Compton, Torrance and Detroit, we know — in our minds and in our bones — that Ferguson, Baltimore, Cincinnati and North Charleston are not far behind.

Here's what else: Black women don't matter. When Ice Cube puts his palm on the head of a topless woman and shoves her into a hotel hallway, locking her out of the room, we're supposed to laugh at her humiliation. When hordes of near-naked women dance poolside in bikinis or perform sexual favors in crowded hotel rooms, we're supposed to forget the now infamous real-life Straight Outta Compton casting sheet that surfaced last summer, calling for scenes featuring "fine girls" who "should be light-skinned" with "really nice bodies," and "medium to dark skin"-toned "African-American girls" who are "[poor], not in good shape."

We're supposed to forget about Dre. In the era of #SayHerName and the fall of Bill Cosby, we're expected to collude with the filmmakers in erasing the January 1991 incident where the rapper-producer grabbed Dee Barnes, a black woman journalist, by the hair and slammed her head into the wall at a nightclub before throwing her to the floor and repeatedly kicking her in the ribs.

"Bitch had it coming," said Eazy-E in a Rolling Stone profile shortly after.

None of this is accidental. The casual degradation of women followed by our laughter, dismissal or collective silence is a defining feature of American life. It is ingrained in our legal system and entertainment. On the smog-choked highways of Southern California, it has seeped from our car stereos and fueled the homosocial bonds of our childhood — mirroring the very ways in which the bonds linking Dre, Cube, Ren, Yella and Eazy relied as much on misogynist vitriol as on giving voice to a generation of black youth who'd had enough with police brutality.

An admirable feature of the ongoing #BlackLivesMatter movement is its intersectional approach to fighting inequality. Black liberation, it says, cannot be realized without black trans liberation, black queer liberation, black women's liberation and so on. It says that, by obscuring N.W.A's most anti-woman transgressions, we are doing the work of the very system that oppresses us and failing to critically reckon with our own capacity for violence.

This is not unique to N.W.A, or to hip-hop or black America. But at a time when black people are being killed by police at nearly three times the rate of whites, and black women are dying in law enforcement custody at an alarming clip, the stakes are higher for us. We need each other.

To reflect on this dynamic as a black, male, Los Angeles-bred disciple of the N.W.A galaxy is to stop ignoring the degree to which hetero-male power and friendship, from our teenage years until now, have been molded by rhetoric that routinely brutalizes black women.

Sometimes, you have to kill your idols.