11 Striking Instagram Photos Celebrating Black Lives Have a Fascinating Story of Their Own

Zun Lee was in Chicago when he first stumbled across the photos. At least, that's how he remembers it. "It could have been Detroit," he told Mic in an interview. "I was traveling like crazy for a project and was in a different city every two or three days."

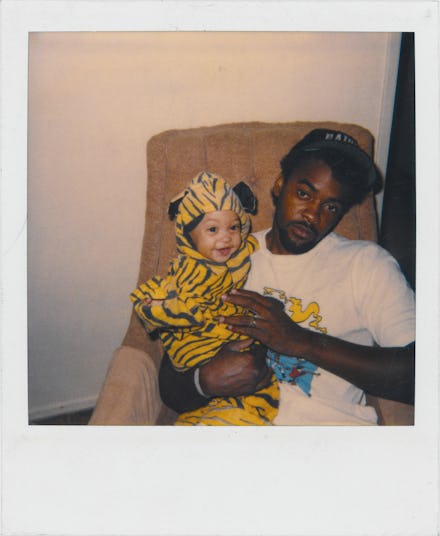

It was 2012. The pictures — dusty and discarded though they were — depicted a rich vision of black America as captured by those who lived it: the mothers, fathers, daughters, brothers and others whose sole qualification as documentarians were that they lived everyday black lives. "Over the next few years, I kept finding more [pictures] like them — at art sales, in dumpsters," Lee said. "There's a whole community of folks buying and selling them on eBay. They're literally everywhere they aren't supposed to be, and the families have no real way of reclaiming them."

A few months after Lee's discovery, a 19-year-old black woman named Renisha McBride was shot to death outside of Detroit by a white man in Dearborn Heights, Michigan, after she'd crashed her car up the street and knocked on his door seeking help. Less than 300 miles to the west, Rekia Boyd was already dead. The 22-year-old had been killed that March when an off-duty Chicago police detective fired his gun into a crowd of her friends.

The names of both women would become rallying points in the burgeoning movement for black lives — an anti-racist protest movement that has marched under the slogan #BlackLivesMatter for the past year and a half. But that was still years away when Lee found the discarded pile of Polaroids on the street. "I thought maybe someone had dropped them," he explained. "I decided to take them home and find a way to at least preserve them, be their custodian for a while."

Things quickly began to evolve. When the #BlackLivesMatter movement coalesced in summer 2014, the sentiments expressed by the protesters began to articulate much of what became Lee's curatorial philosophy. A professional documentary photographer himself, Lee has been archiving the photos he finds and buys and posting them to his Instagram account, @faderesistance, for the past three years. "We are enough as we are," the account's bio reads. "Found Polaroids of African-American families. They knew their lives mattered. Their lives still matter today."

"There's a vibrancy, a pride and joy that's especially moving when juxtaposed against the photos' circumstances," he told Mic. "The fact that people are no longer in possession of these photos could speak to so many circumstances — a sudden move, an eviction, foreclosure, forced relocation. So many things could have happened to get from the moment they were taken to the moment they were thrown out."

These possibilities may complicate matters, Lee admits, especially around the ethics of the project. "As time went on, I started thinking, 'Maybe a lot of people don't want these stories out there,'" he said. "A lot of stories are not stories that people are proud of. Some folks have reached out, saying, 'This is me, this is my so-and-so, I found this person.' ... And there have been a few I'm in touch with who don't want to come forward. They just want me to return the original pictures. They still belong to them, in my mind."

The project also has broader aims. Born and raised in a multiracial black American and Korean household in Germany, Lee is familiar with under-representation. He rarely saw himself reflected in the media images around him growing up, and as a result, his work is heavily concerned with visual identity — especially as it relates to blackness. "A lot has been written about this," he said, "but there's been a lot of work around visual representation of blackness in photography, whether it's in distortion — to ridicule, shame and pathologize — or to counter that with alternative images.

"But there's also a disconnect," Lee said. "Polaroids are sort of this equalizer. They show how people see themselves — they're not performing for an outside gaze."

Frozen in time: Polaroid, which stopped producing its famous instant-print cameras in 2008, is in large part defined by its ephemerality, Lee explained. There are no negatives for a Polaroid photo. What you print on the spot is all that exists of the image, and this, in a way, highlights the special intimacy they possess. "You're performing for yourself here," Lee said. "That's what makes [this project] more current, politically. In this pushback against respectability politics, it says that a respectable, formal photo is not the only way to represent yourself. There's an aspect to these photos that definitely wasn't meant for the white gaze."

"There's an aspect to these photos that definitely wasn't meant for the white gaze."

Although Lee has posted fewer than 100 images to the @faderesistance Instagram and corresponding Tumblr accounts, he says that he has about 2,500 Polaroid snapshots ready to go. He said he plans to keep finding and sharing them as part of the larger project of reclaiming black imagery. "There's a continuum of desire among black people that our communities be seen as more complex than they're being portrayed," he said. "The focus is so often on negativity and dysfunction.

"But we're not seeing the day-to-day, how we really live," he concluded. "And there's political power in representing that rich, everyday life of communities that are still being marginalized."