In Medical First, Gene Editing Cures Leukemia in Terminally Ill Girl

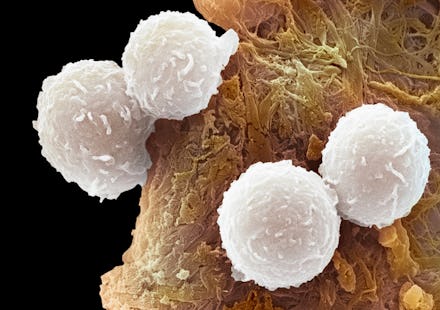

In what could be one of the largest medical breakthroughs in decades, doctors at the Great Ormond Street Hospital in London appear to have successfully cured an infant girl of leukemia using a new technology called gene editing.

The girl had failed to respond to more conventional treatment methods like chemotherapy and a bone marrow transplant. Doctors had given her mere weeks to live before employing the highly experimental technology.

"Her leukemia was so aggressive that such a response is almost a miracle," Paul Veys, a professor and director of bone marrow transplant at GOSH, told Reuters. "As this was the first time that the treatment had been used, we didn't know if or when it would work, so we were over the moon when it did."

Two months after treatment the 1-year-old girl, identified as Layla, was discharged from the hospital. She is currently living at home.

Gene editing, a procedure at the cutting edge of medical technology, involves using a microscopic scissor called transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALEN). TALENs go into chromosomes and "edit" defective genes. In the future, the technology could be used to correct some of the world's historically intractable disorders like cystic fibrosis, hemophilia and Ondine's curse. In Layla's case, genetically edited cells were injected via a one-millimeter intravenous infusion, Reuters reported.

"What makes gene editing so powerful is that you can operate with surgical precision on disease-causing genes," Scott Burger, founder and principal of the North Carolina-based consulting firm Advanced Cell and Gene Therapy, told Mic. "It shows what we can accomplish if we have a solid understanding of how the disease works."

The technology used on Layla was developed by the French biotech company Cellectis, which stole the show from more famous U.S. firms at the American Society of Hematology conference in Orlando on Wednesday, Seeking Alpha reported. The development came despite the abundant availability of low-cost drugs in France, which U.S. pharmaceuticals have resisted, arguing that they would undermine the development of new drugs. The French breakthrough, however, indicates that is not the case.

"It shows what we can accomplish if we have a solid understanding of how the disease works."

The cat's not completely in the bag, though, and Veys was quick to caution that one patient being cancer-free for a few months was far from definitive. "We'll start talking about a cure only a year or two from now," Veys told the Wall Street Journal.

Still, with such dramatic and swift results from a previously hopeless case, it's likely we'll be hearing a lot more about gene editing in the coming years.