Why That Food Pyramid You Were Taught in Elementary School May Have Been Wrong

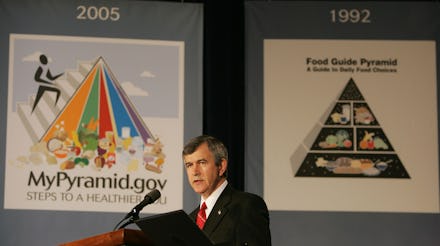

Most Americans are familiar with the "food pyramid" — a diagram developed by the United States Department of Agriculture and touted as a tool for helping people track their food intake. The USDA unveiled the food pyramid in 1992, which was replaced by a new initiative unveiled by first lady Michelle Obama called "MyPlate" in 2011. "MyPlate" is the current nutrition guide for the United States.

The food pyramid was distributed widely in schools, textbooks, and more, with seemingly helpful advice: the daily consumption of six to eight servings of bread, cereal, rice, and pasta; three to six servings of meat, poultry, fish, dry beans, eggs, and nuts; and a limited consumption of fats, oils, and sweets.

However, the food pyramid many of us knew may not have been totally accurate, according to scientists.

Read: 9 "Healthy" Foods With More Calories Than a McDonald's Big Mac

"The thing to keep in mind about the USDA Pyramid is that it comes from the [U.S.] Department of Agriculture, the agency responsible for promoting American agriculture, not from agencies established to monitor and protect our health, like the Department of Health and Human Services, or the National Institutes of Health, or the Institute of Medicine," Dr. Walter Willett, chairman of the Nutrition Department at Harvard University, wrote in his book Eat, Drink and Be Healthy: The Harvard Medical School Guide to Healthy Eating.

"And there's the root of the problem--what's good for some agricultural interests isn't necessarily good for the people who eat their products," he continued.

Willett contended that the food pyramid was even dangerous and ignored scientific evidence. "At best, the USDA Pyramid offers indecisive, scientifically unfounded advice on an absolutely vital topic--what to eat," he wrote. "At worst, the misinformation it offers contributes to overweight, poor health, and unnecessary early deaths."

Did the change from the food pyramid to the new "MyPlate" initiative help any? According to some researchers, the "MyPlate" guidelines don't focus enough on the food research. "I'd like to see the guidelines move away from nutrient targets and toward true, food-based evidence," Dr. Dariush Mozaffarian, dean of Tufts University's Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy, told the Huffington Post.

In 2011, Harvard University's School of Public Health released its own version of the "MyPlate," called the "Healthy Eating Plate," as an more detailed alternative. "Unfortunately, like the earlier U.S. Department of Agriculture pyramids, MyPlate mixes science with the influence of powerful agricultural interests, which is not the recipe for healthy eating," Willett said in the Harvard Gazette. "The Healthy Eating Plate is based on the best available scientific evidence and provides consumers with the information they need to make choices that can profoundly affect our health and well-being."