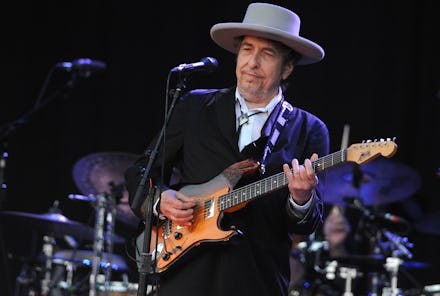

Bob Dylan's best lyrics: The songs that prove he deserves his Nobel Prize

"Beauty walks a razor's edge/ Someday I'll make it mine"

Bob Dylan has always had a fraught relationship with being called the "voice of a generation." But whether he likes or it not, his words drove movements for peace and change. They gave hope and inspired generations of artists to pick up pens and attempt the same.

Thursday, Dylan earned the ultimate accolade for the beauty he brought in the world, becoming a Nobel Laureate, the first to deal in music as their primary medium. He received the prize in literature for "having created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition," as the Swedish Academy wrote in its announcement. Notably, he's the first American to win since novelist Toni Morrison in 1993.

Detractors are already starting to gather across the internet, arguing for other musicians and other artists who deal in more serious mediums. But as many critics have pointed out, few artists have seen their work have a more significant and lasting impact on culture at large.

"He can be read and should be read, and is a great poet in the English tradition," professor Sara Danius, permanent secretary of the Swedish Academy said in an interview following the announcement.

Below are some of the lyrics individuals looking to celebrate or understand the artist can start. A select few are paired with more in-depth breakouts, highlighting overlooked aspects of Dylan's catalog and career.

Half-cracked prejudice leaped forth

— "My Back Pages"

With its hook, "Ah, but I was so much older then/ I'm younger than that now," Dylan's "My Back Pages" seems to confront the ways in which he was held up as the "spokesman for a generation." Appearing on the 1964 Another Side of Bob Dylan, it marked a shift away from his protest songs of his early days that often sum up the whole of Dylan's legacy.

"The big difference is that the songs I was writing last year ... they were what I call one-dimensional songs," Dylan told the Sheffield University Paper in May 1965. "But my new songs I'm trying to make more three-dimensional, you know, there's more symbolism, they're written on more than one level."

When you ain't got nothing, you've nothing to lose.

— "Like a Rolling Stone"

Yes, to dance beneath the diamond sky with one hand waving free

— "Mr. Tambourine Man"

She lit a burner on the stove and offered me a pipe

You'll never know the hurt I suffered

— "Idiot Wind"

One of the angriest and most disdainful tracks in Dylan's catalog, critics have pinned "Idiot Wind" and the album where it appears, Blood on the Tracks, as being a narrative of his painful divorce from Sara Lownds. But Dylan rejected this way of looking at it.

"A lot of people thought that song, that album Blood on the Tracks, pertained to me," Dylan once said of "Idiot Wind." "Because it seemed to at the time. It didn't pertain to me. It was just a concept of putting in images that defy time – yesterday, today, and tomorrow. I wanted to make them all connect in some kind of strange way."

The way it blends base insults like "You're an idiot babe, it's a wonder that you still know how to breathe," and high poetry, like "I kissed goodbye the howling beast on the borderline which separated you from me," was more lyrical sport than confessional. But that's part of Dylan's genius: He has the ability to fool the world into thinking he's baring his soul, while he's off making even deeper cuts.

Let me ask you one question

— "Masters of War"

Darkness at the break of noon

— "It's Alright Ma (I'm Only Bleeding)"

Oh, what did you see, my blue eyed son?

— "A Hard Rain's A-Gonna Fall"

Yes, how many years can a mountain exist

— "Blowin' In the Wind"

The beauty of Bob Dylan's works is that a hundred people can approach them, and all of them will come away with different images and takeaways in their heads. "Blowin' in the Wind" is one of the more unexpected examples of this phenomenon. On one hand, it's Bob Dylan's masterpiece, the Sistine Chapel of protest songs, and that's in large part because its questions — "How many times can a man turn his head/ Pretending he just doesn't see?" — can fit just about any outrage imaginable.

But in that way, the song edges into being more of a philosophical exercise. Are human beings too fallible to heal the world? In racing to put out one fire, will we always invariably cause another? The songs only gives questions, no answers, but that's likely part of the reason it endures.

Every generation asks themselves these questions as they become engaged, conscientious people. Until someone phrases them better than Dylan, his music will endure. The Nobel Prize is just one more safeguard to ensure his words aren't lost to time.