‘Metal Gear’ 30th Anniversary: Why we love Hideo Kojima’s military-themed games three decades later

Thirty years ago today, a modest stealth action game about rookie FOXHOUND agent, Solid Snake, infiltrating the military nation of Outer Heaven was released for the MSX2 in Japan. Though the series it spawned would become known for bombast, Metal Gear and its 1990 sequel are quaint little things. From a 2-D, top-down perspective, your goal is not to kill all the enemies on screen, but to sneak around them. They have fun narratives with some decent twists for that era in game storytelling, but they’re nothing like what was to come.

After 30 years of some of the most iconic and unique (for better and worse) games in the history of the medium, it seems like Metal Gear is effectively dead. Metal Gear Survive launches in 2018, but after series creator Hideo Kojima’s ugly exit from Konami, it’s tough to care. Still, today is a day to celebrate what was rather than mourn what is.

Metal Gear Solid was bold with a big budget

Metal Gear Solid has gained a reputation for endearingly bizarre stories, fascinating characters and jarring shifts between geopolitical screeds and toilet humor — sometimes in the same scene. Though some will tell you the saga’s narrative is genuinely one of the best in gaming, to me that was never the point.

In my mind, Metal Gear Solid stands out because it was always allowed (and expected) to be weird, despite Konami seemingly handing Kojima a blank check for every game. Big-budget mainstream games aren’t supposed to do that. They’re supposed to smooth every sharp edge and make something safe and profitable. Even as the gameplay mechanics eventually became less arcane and more traditionally “fun” over time, Metal Gear never softened itself.

For better and (often) worse, it was allowed to be messy. I’m not going to sugarcoat things, despite my love for the series — Metal Gear frequently crossed lines it didn’t need to cross. It had a cast full of dynamic, incredible women who were frequently the subject of lecherous camera angles and sophomoric jokes. Metal Gear Solid V: Ground Zeroes has one of the most repulsive video game endings ever, in which a bomb has been planted inside a woman’s vagina as an egregiously “shocking” twist.

Things like that are mostly why I take a step back every time I want to talk about Hideo Kojima as some kind of video game genius. I don’t think Metal Gear is worth celebrating because Kojima is a master storyteller. I think it’s worth celebrating because, seemingly until the very end, he was allowed to share his strange ideas with the world using the mighty resources of AAA game development. It’s arguably the only franchise of its scope and scale where, from the outside looking in, one man’s vision dictated its direction.

If you’ve never played a Metal Gear game, I would say Metal Gear Solid 3: Snake Eater is the high point of it all. Set 50 years before the rest, it boldly took away the technology players had grown accustomed to in previous games. You don’t have a decent radar and you have to hunt animals in the Soviet jungle to make sure Naked Snake doesn’t starve. Get hit by a grenade blast and you have to go into a menu and manually treat Snake’s injuries.

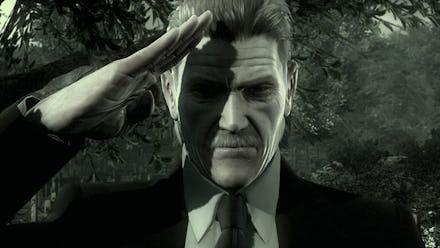

That might not fit your idea of fun, but it was a fascinating experiment in action game design. But its narrative is what makes it king. As Leigh Alexander wrote in a tremendous Vice column in 2014, Snake Eater is “an indictment of patriotism, about the grim manipulation that underlies most of the duties publicly marketed as noble. It’s the salute that hurts, the handshake you don’t want to return, the grave you planted yourself.”

At the end, Naked Snake is given the title of Big Boss by president Johnson and hailed as a hero by the government he’s grown to detest. Though Metal Gear’s politics are often iffy, it was never the kind of jingoistic war game one might expect when looking at the box on a store shelf.

I could go on forever about all of the things that make Metal Gear worth experiencing, but why don’t I just show you?

A Metal Gear solid highlight reel

One of Metal Gear Solid 3’s very best moments has the player climbing an interminably long ladder as the game’s theme song subtly creeps in.

Early on in Metal Gear Solid 2, fan-favorite protagonist Solid Snake is surprisingly replaced by Raiden for the rest of the game, a character some fans liked considerably less. The game’s marketing kept this a secret and reviewers were asked not to spoil it in pre-release coverage. Things get really nuts near the end, as the colonel who’s been giving you orders throughout the game is revealed to be an AI that’s going haywire before spouting nonsense at you.

One of the most famous boss fights in the history of video games is Psycho Mantis in the first Metal Gear Solid. The psychic soldier can read Snake’s thoughts, which manifests in-game as him reading your PS1 memory card and telling you which Konami games you like to play based on your save files. Since he can read your movements, the trick to beating him is to plug the controller into the second port on the console, which drives him mad.

Last, but certainly not least, Metal Gear Solid 4 wrapped up the series’ loose ends, often in clunky ways. That said, its final act is the stuff of legends. Its final boss fight is a fist fight between two broken old men on top of a submarine, where the music and UI take the player on a tour throughout the previous games in the series with regular shifts.

Not to retreat to the comfort of a cliché, but as you can see, there’s nothing else like Metal Gear Solid. Don’t let its unceremonious death cast a shadow over what once was. Every soldier meets his end someday.

More gaming news and updates

Check out the latest from Mic, like this essay about the sinister, subtle evils lurking in rural America that Far Cry 5 shouldn’t ignore. Also, be sure to read our review of Tekken 7, an article about D.Va’s influence on one Overwatch player’s ideas about femininity and an analysis of gaming’s racist habit of darkening villains’ skin tones.