From cemetery to cider: How one Brooklyn couple foraged graveyard apples for their hard cider

I was trying not to think about dead people when I took my first sip.

Raising the plastic champagne flute to my nose, I inhaled the sickly-sweet apple scent wafting from the hard cider. In my glass was Proper Cider’s “Malus Immortalis,” a cider made from apples grown in Brooklyn’s 478-acre Green-Wood Cemetery, the final resting place for Jean-Michel Basquiat, William Meager “Boss” Tweed and various Civil War generals. The cemetery is a National Historic Landmark that’s been around since 1838. On a Saturday night in mid-October, it was open to guests for a live music event.

Spirit-infused cider from beyond the grave

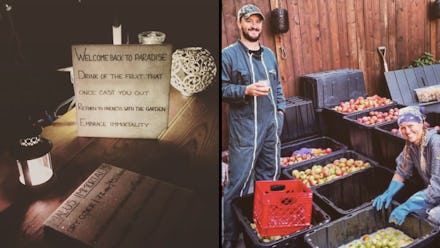

Launched by two Brooklyn locals, Proper Cider’s origin story sounds straight out of a spooky storybook. Jeremy Hammond, a cider hobbyist and television producer living in Brooklyn, was walking through Green-Wood Cemetery in 2015 when he came across an apple that tasted bittersweet. Hammond and his girlfriend, Joy Doumis, later realized the famous cemetery contained many interesting and rare apple varieties like the one Hammond found, and began making cider with the cemetery apples in their backyard.

Hammond had been making cider for decades. Back in 2001, he learned about winemaking while studying abroad in the Loire Valley in France and later had an internship at a vineyard.

“He eventually found a way to scratch that winemaking itch by switching the fruit from grapes to one found everywhere in New York: apples,” Doumis said in an email interview, noting that the process of making cider is closer to that of winemaking than beer brewing.

Proper Cider isn’t a commercial cidery, so you can only taste the cider at pop-ups, which Hammond and Doumis sometimes announce on Instagram. The cider I tried — “Malus Immortalis” — is a joint venture between Proper Cider and Green-Wood. Doumis and Hammond are working with the cemetery to help purchase and plant “American heritage apple trees like Newtown Pippin, Roxbury Russet, Campfield, Harrison [and] Esopus Spitzenburg that would have been around in the landscape in the time that Green-Wood was created,” Doumis said.

She noted the project with Green-Wood functions like a nonprofit: “All proceeds [go back] into supporting the project,” with the goal to help people “enjoy and appreciate the horticultural side of Green-Wood,” Doumis said. Hammond and Doumis host a recurring event at the cemetery called “Pouring Green-Wood,” where the pair discusses everything from cider makers who are buried in Green-Wood — like Horace Greeley, a famous journalist who founded the New York Tribune — to the history of the 100-year old tree that provides most of the apples used in Malus Immortalis.

The duo behind Proper Cider scours New York state during fall to harvest apples for use in their ciders.

“We use different apple blends every single year depending on what we can get our hands on ... the variety of apples used dictates the final taste, just like grapes in wine,” Doumis said, adding that she and Hammond always start from real apples and never buy juice.

They ferment the ciders for five or six months in their Brooklyn apartment. But they don’t always bottle right away — they sometimes let the cider rest in the barrel for years, Doumis noted.

Could decomposing corpses be seeping into the soil that grows this fruit? In a word: maybe. According to the Green-Wood site, the cemetery allows people to have “green burials,” where bodies are enclosed in biodegradable containers or caskets made from natural materials. It’s an eco-conscious process because it allows the body to decompose more quickly, Modern Farmer reported, noting that green burials “accelerate the process of being broken down and becoming one with the soil.”

That might be a boon for soil quality. Though robust research on the topic is limited, a University of Tennessee study found that human remains enriched soil quality compared to soil that didn’t have human remains.

Giving life to cemeteries around the country

Green-Wood isn’t the only cemetery that grows fruit later used to make boozy beverages. Outside of San Francisco, the Holy Sepulchre Cemetery planted vines that bear grapes. Their wines — including cabernet sauvignon and zinfandel — have even won prestigious awards. (The wine label is called “Bishop’s Vineyard.”)

The Holy Sepulchre Cemetery is one of three California graveyards that have functional vineyards. Some officials in the Catholic Church hope the grapevines make graveyards and death less intimidating. “The cemetery doesn’t seem like such a sad and fearsome place when you go there and see the vines,” Bishop Michael C. Barber of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Oakland told the New York Times.

I experienced this for myself when I cautiously sipped Proper Cider’s “Malus Immortalis.” The cider’s bold, bitter flavor washed over me. Sour, dry tannins and a pleasant bubbly carbonation sparkled in my mouth and left a lingering sweetness. It wasn’t creepy — it was alive. For one night, the cemetery, with its dark rows of headstones and winding pavement paths, felt magical.