The Charleston 9

This article is a part of the Black Monuments Project, which imagines a world that celebrates Black heroes in 54 U.S. states and territories.

Black churches are hallowed ground in the United States. Since slavery, they have served not just as a spiritual home and sanctuary for marginalized people, but as a space where community is built, politics are forged and resistance — from slave revolts to civil rights protests — is planned.

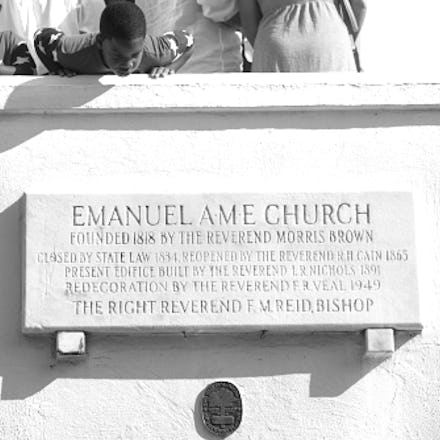

Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina, is no exception — which is part of why what happened there the night of June 17, 2015, was not just a devastating human tragedy, but a symbolic one that struck at the heart of what many black Americans hold sacred.

This was intentional, of course. Dylann Roof, the then-21-year-old white supremacist who murdered nine black people there that night, knew what he was doing. In addition to embarking on a months-long tour of sites vital to American white supremacy before his attack — a slave plantation, a Confederate graveyard and the like — he’d developed a working list of black churches, settling on “Mother Emanuel,” as it is known, because, he told investigators, he knew it was a black hub.

The details of Roof’s actions have been excavated at length in the years since: how he was welcomed into and sat in on a Bible study; how he waited until the session was well underway before pulling a handgun out of his fanny pack and opening fire on the attendees — killing six women between the ages of 45 and 87, the 26-year-old great-nephew of one of the women, a 74-year-old male pastor and the Rev. Clementa C. Pinckney.

But Roof’s cruel inhumanity is best understood in contrast to the deep humanity of those whose lives he stole. Myra Thompson, 59, was a beloved retired school teacher and Bible study instructor whose devotion to the church and its parishioners was matched only by her love of family, according to those who memorialized her. Sharonda Coleman-Singleton, 45, was a high school speech therapist, helping young people overcome their difficulties communicating. The Rev. Daniel Simmons Sr., 74, was a pastor known as “super” to those close to him because of his vast array of talents and interests: his leadership of his church, his role as a great friend and confidant, his love of jazz music and cars.

Tywanza Sanders was the youngest of Roof’s victims, at 26. Constantly dedicated to self-improvement, Sanders died trying to convince Roof not to kill the Bible study attendees, eventually shielding his great-aunt Susie Jackson with his own body as the killer opened fire. For her part, Jackson, 87, had two children officially, but more or less raised up to 50 of her other relatives, including nephews and great-nephews, according to her family. She hosted massive Sunday dinners at her home to gather her family close.

Pinckney, 41, was a revered local leader and activist. He persistently immersed himself in social justice work, balancing his busy life as a family man with hosting vigils for people like police shooting victim Walter Scott, all while serving in the state House of Representatives.

The Rev. DePayne Middleton-Doctor, 49, was a beloved mother of four and a minister at the church. She was known for what friends and family described as an “angelic” singing voice that made worshipers stand up, clap and burst into tears. Ethel Lance, 70, was known for her deep inner strength. She fought doggedly to keep her family together and united in light of several tragedies, including the death of her husband in 1988 and of her 53-year-old daughter from cancer in 2013.

Finally, there was Cynthia Graham Hurd: the 54-year-old family matriarch whose 31 years of service to the Charleston County Public Library system sharpened her into a consummate storyteller, a woman whose tales “went on and on and on,” as her brother put it, the Washington Post reported, “because she included the research and all the footnotes.” All 16 of the library system’s locations were closed the day after her death in mourning and out of respect. The branch she managed was named after her in 2015.

Entire books could be written about the love and service these nine individuals generated for their families and communities. What will likely unfold, instead, is continued coverage of the man who killed them: a hateful, mediocre and unimaginative bigot who could find no better explanation for his frustrations than that black people were probably causing them, and thus needed to be disposed of.

The Charleston Nine deserve better than this. They deserve to be remembered in their individual splendor, with all their nuances, flaws and unique radiance intact. These nine black men and women may have sparked a massive nationwide debate about the appropriateness of flying Confederate battle flags over American statehouses and in other official capacities, via their deaths, but it’s their lives that deserve the most celebration.