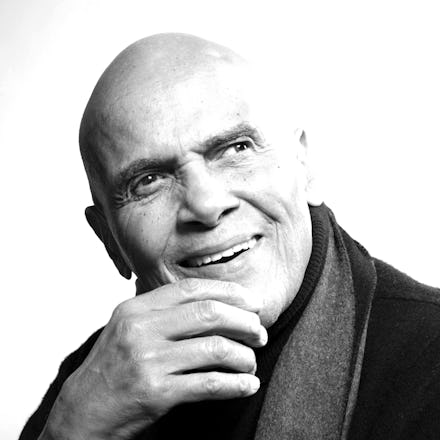

Harry Belafonte

This article is a part of the Black Monuments Project, which imagines a world that celebrates Black heroes in 54 U.S. states and territories.

Harry Belafonte once asked that his epitaph read simply, “Harry Belafonte, patriot.” Indeed, his life and work tell the story of a citizen who, possessing a staggering amount of energy and talent, committed himself to reshaping American society.

His path reads like a guided tour through the struggles and achievements of black America. Born in Harlem, New York City, to parents from Martinique and Jamaica, he spent some of the 1930s living with his grandmother in Jamaica. Upon returning to New York City, he enrolled in high school but did not stay long, according to a New York Times review of his memoir. He had dyslexia and soon dropped out to join the Navy: World War II was underway.

After returning from the Navy, he found work as a maintenance man. In a chance occurrence, an actress gifted him a ticket to a local theater, the New York Times review said. After seeing the show, he was hooked and began his pursuit of an acting career. He befriended a young Sidney Poitier, and the pair struggled together as aspiring actors in New York City, taking acting lessons alongside Marlon Brando and going to local plays together on a single ticket, according to a New York Times op-ed. To pay for acting lessons, Belafonte began moonlighting as a singer and performed with jazz legends Charlie Parker and Max Roach. He found a mentor in Paul Robeson, who would later introduce him to Eleanor Roosevelt and other civic luminaries, the Guardian reported.

His singing and acting careers blossomed in parallel. In 1954, he won a Tony Award for his starring role in John Murray Anderson’s Almanac. Two years after, he released the album Calypso, which became the first album by one artist to sell 1 million copies and stayed at No. 1 on the Billboard charts for nearly eight months, according to AllMusic. Calypso introduced the U.S. to the rhythms of the Caribbean, a legacy Americans still enjoy.

The album’s hit song was “Day-O,” a Jamaican folk tune recounting the daily struggle of working-class people. This theme of solidarity with marginalized people has been a driving force for his work rather than a philanthropic footnote. Perhaps more than any artist of the past 60 years, Belafonte has fought for social justice with unwavering consistency.

At moments when he could have comfortably settled into his fame, Belafonte made his voice heard and bore the repercussions. During the McCarthy Era, he was blacklisted until TV personality Ed Sullivan broke the blacklist rules by allowing Belafonte on his show.

During the civil rights movement, Belafonte made no secret of his stance for racial justice. Through fellow Harlemite Adam Clayton Powell Jr., Belafonte became a close friend and supporter of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., the New York Times reported. Throughout the 1960s, he provided personal support to King’s family and fundraised for freedom rides, the Mississippi Freedom Summer, the Birmingham Campaign and bail costs for jailed activists. Coretta Scott King reportedly wrote of him, “Whenever we got into trouble or when tragedy struck, Harry has always come to our aid, his generous heart wide open.” Belafonte also helped organize the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, where he spoke at the podium and marched alongside his old acting friends Poitier and Brando.

After the civil rights movement, much of Belafonte’s civic focus shifted to global humanitarian aid and political critique. With legendary tennis player Arthur Ashe, he founded Artists and Athletes Against Apartheid, pushing for the end of South Africa’s apartheid regime. He was one of the central organizers of USA for Africa’s “We Are the World” campaign and participated in the Live Aid concert, along with humanitarian trips to Senegal and Rwanda.

By the 1980s, he turned his attention toward helping pave the way for new artists. Hip-hop had arrived on the scene, and Belafonte embraced the movement. He produced and scored Beat Street, a seminal film on emerging hip-hop culture and its pioneering breakdancers and graffiti artists. In his travels to Cuba, he once pushed for the Castro government to embrace the budding Cuban hip-hop community.

At 90 years old, Belafonte has risen to elder statesman status. He is now an American Civil Liberties Union ambassador for juvenile justice reform and has served as a grand marshal of the New York Pride March, an honorary co-chair of the Women’s March and was appointed as a UNICEF goodwill ambassador in the 1980s. He founded Sankofa, a social justice organization that partners with influential artists to tackle issues related to violence, incarceration, income disparity and immigration. Sankofa counts John Legend, Common, Angélique Kidjo, Q-Tip, Macklemore and Robert Glasper among its partners.

Belafonte’s work has had a persistent and far-reaching influence on American culture. As an artist, he has soared to the highest levels of achievement, winning a Tony Award, an Emmy Award, an honorary Academy Award and multiple Grammy Awards.

As an activist, he has been central to our nation’s greatest moments of change. Unlike many of his peers in entertainment and the civil rights movement, we haven’t yet had to shed tears of loss for him. But every waking moment of his life warrants tears of triumph.