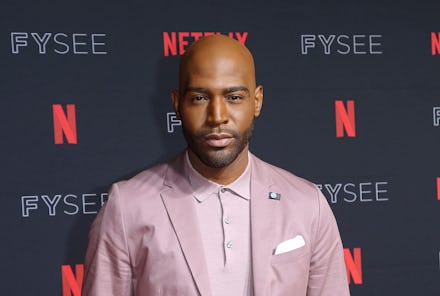

‘Queer Eye’ star Karamo Brown on meeting with the White House — and Adam Rippon’s refusal to do so

Of all the guys on Netflix’s reboot of Queer Eye, Karamo Brown — the “culture” expert — has perhaps the most unique role. Rather than help transform the show’s Atlanta-based contestants from the outside in, via a snazzy haircut or a perfectly executed French tuck, Brown works from the inside out, coaching and counseling the subjects through their deepest emotional traumas.

To do so, he calls on his experience as a counselor and psychotherapist, an area of expertise he has parlayed into political activism, as well. Most recently, Brown met with Karen Pence’s chief of staff in April to advocate for the importance of the arts for LGBTQ youth. That moment was a divisive one within the Fab Five: In a recent interview with Vulture, Queer Eye’s grooming expert Jonathan Van Ness called out Brown for the meeting, arguing it was pointless because the Pences’ “don’t like you, girl.”

In a recent phone interview, Karamo discussed the show’s recently released second season, his approach to helping the show’s subjects, whether being the Fab Five’s sole father influences his methods and why he thinks it’s important to meet with conservative politicians — especially when they don’t value you as a human. The following interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Mic: How has the reaction to Queer Eye’s second season compared to the first?

Karamo Brown: The reaction has been just as powerful as the first time around. I would say the biggest reaction is my own. I only binged the first season once when it came out and didn’t watch it again. I’ve binged season two maybe four times already.

What is it about these new episodes that grabbed you in a way that the first didn’t?

KB: It wasn’t that the first didn’t grab me, it was just that we just finished shooting [both seasons back to back], and we were so close to everything from when we finished shooting to when we started doing press that my mind couldn’t grasp watching this. I don’t know, there was something about it. But now, there’s been this long period of time — it’s almost been a year from these episodes now — it feels like, “Oh my gosh, now I can watch and enjoy and not be critiquing every moment.”

Also, I love that this season they, for me, define and show my role a lot clearer than I think they did for the first season.

Correct me if I’m wrong, but you’re the only one of the Fab Five who has kids, is that correct?

KB: I am the only one.

How has that informed the way that you interact with the younger people on the show like Tammye’s son Myles or Sean, from episode seven? Do you find that you become like a parent to them, in a way?

KB: To be honest with you, no. I would say my training as a social worker and a psychotherapist informed that. I’ve worked with LGBT youth for almost 10 years, that was my clientele, and my training has given me an insight to connect with people really quickly and allow them to open up very quickly, and get them to question what issues are blocking them. And I think I do that as a father, but it’s my training.

One of the things I’m most proud of with the show is the emotional response from the audience, and a large part of that is because that’s what I’ve been doing as a career, and a lot of people don’t realize that it takes a skill set to be able to have people open up and challenge years and years of behavior in less than a week.

Can you break down that process a little? Obviously you guys get a bit of a briefing about who these people are before you meet them, but when you interact with them for the first time, what are you looking for and how do you start crafting a plan around them?

KB: If you notice on the show when we’re getting the dossier, for me it’s always like, “He wants to get married.” And I have to use that little nugget that’s going to lead me to a breadcrumb that’s going to lead me to where the real emotional issue is. The producers don’t really get to the emotional crux of it before we get there.

The minute I walk into that house — for me, investigating that first time is crucial. I am really investigating trying to find, like, photos, trying to see what was going on with their life, what was going on with their family, who they were before this, who they hope to be. And in my first conversation with them, I have a bit of a counseling session where I begin to hammer them with questions, hard questions, that probably no one — let alone a stranger — has ever asked them.

There’s always a specific point where you can see the trauma triggers happen, and it’s about helping that person get to that point.

Sometimes the event you plan for each contestant is performative, or poetic in a way. Like, in the episode with Ari, you take him to get a lie detector test, which was very theatrical, as opposed to a concrete counseling session. Is that something you would do in a real-life situation or is that just a way to create an interesting moment for television?

KB: I wouldn’t have done it in my regular profession because I’d actually have five months to work with someone, or a year or two years, but for the show, it’s a visual medium and you need physical representations.

So, even for season one, in AJ’s episode, when I take him to the ropes course it’s because our conversation was all about his fear — the moment that his father passes away, he realized he shut himself off and was scared to make any new advancements in his life. It was like, “I can’t go past this spot.” So me taking him on this ropes course was to say, “This is the physical representation of the conversation we had.”

The same was with Ari in season two. It’s the physical representation of that lie detector test. I don’t care about the results, but we’ve had the conversation trying to get to the core of, “Why do you feel like you have to lie? Why do you believe there’s gray area?” So now, the audience gets to see, “Oh, that’s what the conversation was.” Even with Ari, I’m very proud: He finished school, he has a great job and he’s maintaining it, and a large part of that was because what was blocking him has now been unblocked.

A lot of times, I’ve had people come up to me and say, “We love you so much on the show, but we didn’t really get what you did until season two because it’s more clear.” And if we’re ever blessed to get a season three and four, I’m going to make sure it’s defined even more, that people understand my role is to fix the insides.

On a slightly different note, I know a lot of the conversation around the show has to do with you being in the South in these veins of intense conservatism, and in a recent interview with Vulture, you and Jonathan were trading jabs about your meeting with Karen Pence’s chief of staff. Is that a topic of conversation you all have with each other — how to approach people with different viewpoints from yourself? Do you differ in opinions from the others?

KB: Yes, 100%. Jonathan and I are the most political ones out of the group, I would say, and it’s also ironic because I’m the oldest out of the group and Jonathan is the youngest. So, our approaches are different, but our goal is the same. And for me, it’s always been that I have to reach out to people who have shut me out or who try to shut me out. Historically, that’s the only way as African-Americans, as gay people, that we have been able to affect change.

If someone says, “that black person is not allowed to be in the restaurant,” we sat in the restaurant. We didn’t say, “We cannot sit in the restaurant; we’re gonna go somewhere else.” Same with being a gay man or the LGBT community. My approach has always been, “How do you find ways to make sure these places that want to deny you access or want to pretend as though you don’t exist, have to see you and have to hear you?”

I think at that point, that’s when you humanize yourself. When we were having that discussion [at Vulture], for Jonathan, he is a young, vibrant activist, and I love him so much. He and I will sit and watch RuPaul’s Drag Race, we’ll talk about the craziest things, then switch to MSNBC and CNN and Fox and watch the news all day long, and the guys are always looking at us like, “What is going on here?”

But, what I love about that is, he is young and saying, “I’m not going there — I’m going to be on the streets and I’m going to march, and I know you don’t like me so I’m not gonna come there.” But he’s younger, so his approach is different from mine.

It’s not a wrong approach. In fact, I think it’s actually a great approach because we need both.

The last notable example of a similar situation is when Adam Rippon said he wouldn’t speak to Mike Pence ahead of the Winter Olympics. When you saw that, was that a choice you disagreed with? Based on your own approach to these things, I’m interested in how you read that moment.

KB: I think Adam Rippon was right for his feelings. It’s similar to Jonathan. I’m gonna be transparent: We all have certain amounts of privileges, which allow us to inform and shape our behavior and the things we do.

These are two white men who, historically, have not been shut out of rooms. Though they are both gay and both have what society would deem effeminate qualities that have caused them harm and pain, there’s still sort of the privilege of, “As I walk through this world, there are certain people I don’t need to reach out to because I am a white male.” And is there anything wrong with that? No. Should Adam Rippon have met Mike Pence? No, he should not have.

But for me, because of the fact that I understand I have to step into these rooms — if someone said to me, “Meet with Mike Pence,” you’re damn right I would. I would meet with him, and I would reach out to him. Do I feel like anything I could say would reach his heart? Possibly. Do I believe that I could affect legislation that could help the next generation or help this administration stop seeing LGBT people as dirty and disgusting and less than human? Possibly. But I won’t know unless I try.