Could this California bill start the next evolution of police reform?

When California Assemblymember Shirley Weber introduced Assembly Bill 931 — a newly proposed amendment aimed at discouraging deadly force by California police — her words conveyed the seriousness of the battle ahead. “We have been deeply saddened and frustrated by the killing of black and brown men by law enforcement,” Weber said during a press conference in April. “It seems that the worst possible outcome is increasingly the only outcome that we experience.”

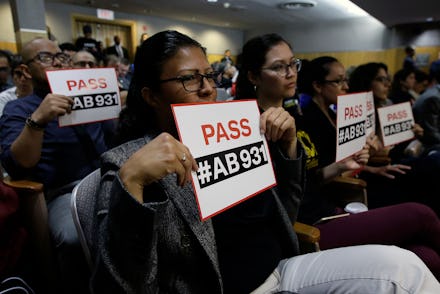

Now, Weber and several activists are working to keep the bill alive ahead of a vote during Thursday’s hearing. If the bill — currently held in “suspense” — receives enough votes from the Senate Appropriations Committee, it will move on to a vote by the full Senate, then be sent back to Assembly for another approval vote by the end of August. If not, AB 931 will represent another lost fight for California’s police reformers.

Weber’s proposal came weeks after Stephon Clark, an unarmed black man, was killed by two Sacramento police officers in his family’s backyard. Clark’s death has been one of several high-profile police-involved killings in 2018, including that of Antwon Rose, an unarmed 17-year-old who was shot and killed in late June.

AB 931, also known as the Police Accountability and Community Protection Act, seeks to save lives of people like Clark and Rose through a seldom-employed semantic approach to police reform. According to current legislation, police may use “reasonable force” when threatened with danger. But this new California bill seeks to remove this legislative loophole, and change “reasonable force” to “necessary force.” In doing so, the amended law would prohibit deadly force by police unless “necessary to prevent imminent and serious bodily injury or death to the officer or to a third party.”

If passed, AB 931, put forth by Weber and co-author Kevin McCarty, would state California police officers should only use deadly force when all other interventions, such as de-escalation tactics, have been exhausted. In proposing the bill, Weber and McCarty seek to end a dark pattern in American policing — where black people, who are 13% of the country, account for 25% of killings by police. As the usage of body cameras makes little progress in preventing police killings, California’s proposed approach to protect black lives may represent the next evolution of police reform.

The story of Clark’s death is as tragic as it is familiar. Police officers, who said they saw a weapon, fired at Clark 20 times before leaving the 22-year-old father of two dead outside of his home. The official autopsy found he was shot a total of seven times, with three shots in the back. And, like Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, Tamir Rice and countless other black victims, no weapon was found in Clark’s possession. He only held a cell phone.

Clark’s death not only sparked nationwide protests — it also signaled the reinvigoration of California’s Black Lives Matter movement. For months following the fatal shooting of Clark, Sacramento activists — including Clark’s brother Stevante Clark — continued to protest peacefully, demonstrating in front of the district attorney’s office, shutting down freeways and more in search of justice for Clark’s death.

During Weber’s AB 931 announcement, Tanya Faison, the founder of BLM’s Sacramento chapter, used her time at the podium to elevate the seemingly countless names of those abused or killed by police in the Sacramento area. She concluded her catalogue of lost life to say she was thankful for this legislation. “We need repercussions,” she said. “We need community oversight.”

The gravity of Faison’s words are corroborated by a uniquely American epidemic. Since 2015, American police have shot and killed nearly 1,000 people each year, according to the Washington Post’s police shooting database, which is astoundingly higher than most developed countries, many of which experience fewer than 10. Since Clark’s death, 415 more people have been shot and killed by U.S. police — nearly three people each day — bringing the total to 540.

Despite such staggering statistics, in recent years, the fight for police reform has felt increasingly unwinnable. Of the officers arrested for manslaughter between 2005 and April 2017, roughly two-thirds were not convicted or the case is still pending. And of 15 high-profile police brutality cases from 2014 to 2017, only one resulted in sentencing.

“When it goes to some level of hearing ... it passes a test that says it’s fine because it was ‘reasonable’ to be afraid,” Weber said, explaining why police officers so often aren’t held accountable for extrajudicial killings. “And right now, they don’t have to justify the strategies they used in each incident. They only have to say they felt fear, and acted upon that fear.”

As a result, Weber has grown more concerned with what happens before the trigger is pulled. “The real key is to prevent the shootings. In certain communities, police don’t employ all of the strategies that should happen before shooting occurs.” Weber went on to describe how, when speaking to community members, many people believe that lethal force is a last resort — and in most communities, that is true. But according to Weber, “in communities of color, or poor communities, escalation is more likely.”

While many agree that lethal force should be limited, one barrier stands in the way of this bill’s success: the political power of police.

Police pushback

If this legislative language is changed, police accused of unlawful killing will need to prove they exhausted all potential intervention before deadly force — including de-escalation tactics, such as empathetic communication, tactical wait-time and patient negotiation. As a result, the new bill has the potential to increase the likelihood of officers who unnecessarily intervene with violence facing prosecution.

For that reason, the bill has experienced a tremendous amount of pushback from police organizations. To date, AB 931 has been derided and rejected by the California Police Chiefs Association and other police organizations. PoliceOne.com went as far as to title one article “4 reasons California’s deadly force proposal deserves to die,” using the last three words of the headline to incriminate and intimidate.

Moreover, policing is fraught with relationships too easily damaged by political opposition. As David Harris, criminal justice expert and professor of law at the University of Pittsburgh, explained in an interview, another major reason police killing cases often go unpunished is because “there’s a reluctance by many [district attorneys] to prosecute. They work hand in glove every day with the police — that’s why there are so many calls for independent investigators.”

With this concern in mind, Weber has aimed to work closely with law enforcement. “We tried to convey to police that this is not a ‘gotcha bill,’” she said. “We have not advocated as people who are trying to take their authority away, or give it to an outside investigator. We have put forth what we think, and what researchers have shown, is a good policing practice.”

However, Weber’s confidence in support from the police is minimal. “We’ve never had law enforcement’s buy in unless they write the bill themselves,” Weber said. “I don’t anticipate getting their support unless we get rid of the bill and change it into something that addresses a different issue. I’m saying that having asked them for their recommendations to amend this bill, but they’ve shared none.”

But even without police support, organizers against police violence remain stalwart. AB 931 has already received widespread support from the American Civil Liberties Union, Anti Police-Terror Project, PolicyLink, Black Lives Matter and other influential organizations. And if passed, it may jumpstart a national conversation around similar legislative language.

Jump-starting a national conversation

When asked about AB 931’s potential national impact, Harris was hopeful. “It’s not unprecedented for one state to start something that will find it’s way into other states. And California always has a big impact. It’s a large state and very populous, and has often led the way in legal matters so it can have a big impact. And if we get data that it’s having an effect — and an effect that other people demand — the clamor for it will get louder.”

And laws like AB 931 have already begun to demonstrate how legislation can save lives. “States that adopt this policy are about 16% less likely to kill people,” Campaign Zero’s Sam Sinyangwe said in April. “Police departments that decide to adopt this policy voluntarily are 25% less likely to kill people.”

Sinyangwe claimed to be “optimistic” about the passing of AB 931, the likes of which has already been adopted in states such as Tennessee, Rhode Island, Delaware and Iowa. Now California is following suit in hopes that other states will follow. Weber believes “this will be a game changer” for national conversations against ending police violence, and will help inform the training of police officers as well.

As California’s law is currently written, police perception becomes an imperfect proxy for reality, making it easy to mistake bias for truth. And in a country plagued by a legacy of racial oppression, the law as it currently stands will fail to protect people of color.

Weber closed her interview with an important reminder. “Words matter, so this bill is really getting to the heart of the issue, which is people’s perception as they’re policing, and ability to use better strategies to get better outcomes.”

Now, as activists and assembly members work to honor Clark’s life, and the lives of countless Americans who’ve died at the hands of police, bills like AB 931 demand police act on their most basic mandate: to protect and serve us. All of us.