I Grew Up in the Segregated South, A Descendant Of Slaves

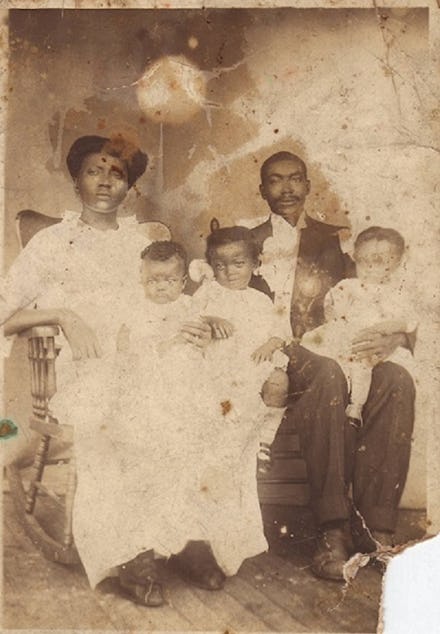

I am a descendant of slaves. I have been called, "colored," a "negro," and a "nigger."

But still, I believe that the promises of the Gettysburg Address — that "all men are created equal" — are unbroken. And I love my country.

I grew up in Tallahassee, Florida, when the South was still segregated. When I was about 5 years old, I asked my mother why we had to sit at the "colored" lunch counter in the back of McCrory’s when the better one for white people was empty. She leaned close, looked around to make sure she was not overheard, and whispered, "We don’t have to."

It was my first time learning some lessons as a black boy living in the segregated South: Never let a white person know what you really think, and follow the rules.

(Photo: McCrory’s "white" lunch counter "sit-in," via Florida Memory)

Lincoln delivered the Gettysburg Address 150 years ago today. In it, he redefined his mission: to free the slaves in the Southern states. My great great grandmother remembered her owner calling all his slaves together. He told them about the Emancipation Proclamation and said they were free to make a choice: They could leave his land or become sharecroppers on it. The "40 acres and a mule" option was not offered. Slavery was brutal and ugly.

The Union won the war, President Lincoln was assassinated, the Constitution was amended, and the slaves were freed. But slavery was replaced with lynching, the KKK, and legal segregation (i.e., de jure segregation).

The last lynching in Pennsylvania was in 1911 at the Pennsylvania town of Coatesville. It is a three-hour drive on Highway 30, "The Lincoln Highway," from Gettysburg. Florida led the nation in lynching per capita in the first part of the 20th century. The lynching of Claude Neal was in 1936.

Lynching and race riots terrified all African Americans. "Public lynching as spectacle" became a social event. Post cards were mailed to friends and family.

(Photo: All of my uncles served in World War II, except one. He had lied about his age to get a job working in laundry during the Great Depression. He lost his right arm when it was caught in a steam press.)

When I was growing up, the public library was not segregated. It was my emotional safe place and gave me access to the books that taught me that there was a much larger world out there. It wasn't until years later that I learned of my mother’s fear and anxiety when she took me to apply for a library card. She was terrified that it would be similar to voter registration, where there were whites on every side of you, police present, and many resentful, angry people.

(Photo: Voter registration in Tallahassee, via Florida Memory)

(Photo: the public library in the 1960s, via Florida Memory)

Today, segregation still takes various forms. Sunday morning is the most segregated time of the week. Churches, with a few exceptions, remain segregated. Large university dining halls are visual proof, as separate races stay divided. Black Americans are often poor, unemployed, and treated unfairly by the criminal justice system.

I always found this day, November 19, to be an annoying reminder of the Gettysburg Address. It was just another promise from a politician: easily made, never kept, always broken.

I was wrong.

Lincoln's speech contained two promises to slaves and both have been kept. The first, to end slavery, was fulfilled when the Thirteenth Amendment was ratified in December of 1865. The second promise was the opportunity to participate in the political process.

There was no third promise of a perfect America in which the dream "all men are created equal" would magically occur.

Today, 150 years later, lynching "as a social event" does not occur, legal segregation does not exist, and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 guarantees the right to vote. The political system of the U.S. will always have issues of the day; Lincoln never promised that would change.

I am glad to have finally realized that some politicians keep their promises.