How LGBT Activists Accidentally Helped Pass Uganda's Anti-Gay Laws

Why did Uganda risk certain pariah status and economic backlash in order to pass its notorious anti-gay bill, one that governs something so trivial as sexual preference?

The answer, in the end, was cynical. It's politics.

This shouldn't surprise Americans. It was a simple political calculation by President Yoweri Museveni designed to keep him in power past another election, and it was the short attention span of the international community that helped make the choice for him.

When MP David Bahati introduced the bill in 2009, conservative religious leaders — many funded by U.S. evangelicals — had already for years sought to convince locals that gays were pedophiles out to molest their children and practice bestiality. According to a recent Pew poll, 96% of Ugandans believe that homosexuality should not be tolerated in society. Until this month, the law's fate was unclear.

Image Credit: AP

Museveni publicly waffled over the bill and was aware of its diplomatic repercussions, telling parliament to "also take into account our foreign policy interests." In private, he admitted that homosexuality had always existed in Africa, even as he secretly funded groups that whipped up homophobia. As one Western ambassador said of the president, "He may be mad, but he's not stupid."

But as foreign LGBT activists and western governments pushed to have the bill killed, it became the one Ugandan story making headlines, raising its stakes and transforming what was a potentially popular law into Museveni's political trump card. Distressingly, Ugandans began blaming their gay brothers and sisters for the negative coverage, thereby pushing the hand of the bill's supporters in parliament.

Should activists and Western governments not have decisively lent their support to the beleaguered LGBT community in Uganda? Of course not. But outsiders struggled to grasp that their rancor over the law was inconsistent with a long silence during Museveni's increasingly dictatorial 28-year rule and his flagrant corruption, disregard for human rights and suppression of opposition parties, problems that made life difficult for all Ugandans. None of those issues presented the viral-friendly morality play of an apartheid-esque law.

It was easy to miss that Uganda has been engaged in an actual war in South Sudan, which shares responsibility for committing crimes against humanity. But this was not why Uganda was in the news. Nor was it the Ugandan security forces "impunity for torture, extrajudicial killings and the deaths of at least 49 people during protests in 2009 and 2011." Nor was it for its track record of "military commercialism" and the expropriation of diamonds and gold from conflict zones.

Ultimately, as Jocelyn Edwards writes, it was the gay bill and Museveni's cynical ploy to "distract from an acute governance deficit in the nation" and build a "flimsy smoke screen for Uganda's more pressing problems" that made headlines. Only days before the anti-gay law, Museveni signed an "anti-pornography bill" that bans mini-skirts.

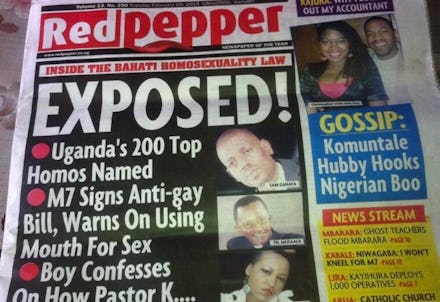

The bill, of course, has terrible implications for the LGBT community, which has been pushed into smaller and smaller spaces, subjected to increased violence and whose members could now potentially spend their lives in jail for having a boyfriend. Indeed, the day after the bill was signed, a local tabloid, Red Pepper, offered up the names of "Uganda's 200 Top Homos" (Museveni's half-brother is part owner of the paper, and it's believed that many on the list are in fact members of the opposition set to be rounded up under the new law.)

In 2011, David Kato, one of Uganda's foremost gay activists, was bludgeoned to death with a hammer while taking a walk in Mukono. A few months earlier, Rolling Stone included him among pictures of "exposed" activists under the headline "hang them."

There's been a lot of talk about the embarrassingly bad science behind the bill, which claimed, among other things, that men could became gay after experiencing erectile dysfunction. Though Museveni mentioned the study, it was really because of flagging support within his own party that he put pen to paper on Monday. By then, messaging made the law out to be Uganda's last stand against neo-imperialism.

A spokesperson said that Museveni "wants to sign it with the full witness of the international media to demonstrate Uganda’s independence in the face of Western pressure and provocation."

Uganda was immediately chastised by Obama and called "barbaric" by commentators, recalling the never completely retired trope of the black African savage who must be civilized. Ironically (or tellingly, perhaps), Uganda's existing ban on homosexuality, like most that remain in Africa, dates back to the 19th century, a relic of British colonialism.

Think of the U.S. for a moment. Of the 29 states that ban gay marriage, more than two-thirds enacted limiting laws either in 2004 or 2008, during one of the bloodiest years of an unpopular war in Iraq or at the climax of a financial crisis. As Americans died in the Middle East and retirees lost their life savings, voters and legislators chose, over others, the same moral issue as Ugandans.