A New Experiment Reveals Who Your Congressman Is Really Working For

A new experiment has revealed who your congressman really works for, and it turns out the old maxim is true: in D.C., money really does get you access to anyone. Politicians are significantly less likely to pay any attention to your concerns unless they've got the scent of a fat wad of cash in your wallet.

On Tuesday, Yale University grad student Joshua Kalla and University of California, Berkeley colleague David Broockman released the initial results of a study that measured whether the prospect of campaign donations altered the behavior of our congresspeople and their staff. In the controlled experiment — enacted with the help of liberal advocacy group CREDO Action — the researchers split 191 members of the same party in Congress (likely Democrats) into two groups. Both recieved an email asking for support for a chemical-banning bill and inquiring about the possibility of an in-person meeting.

The catch? One set of congresspeople recieved the subject line "Meeting with local campaign donors about cosponsoring bill" and mentioned that a dozen or so CREDO members "who are active political donors" would be in attendance. The other email only mentioned "local constituents."

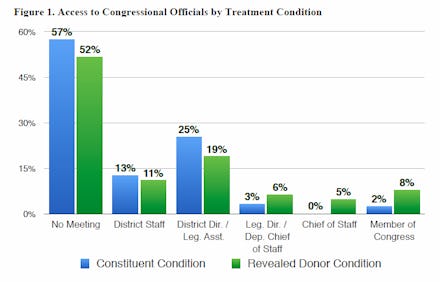

After the emails were sent, when donors were involved, 12.5% of offices responded saying the congressman or their chief of staff would be available. On the other hand, only 2.4% replied when it was only constituents. And the study is likely underestimating the effect of money, because the congressional office had no idea who the donors were or how much they'd given in the past.

In other words:

The results mapped:

Why does this happen? Broockman says that the research is a direct result of the Supreme Court decision Citizens United, which argued lawmakers are only influenced by direct contributions to their campaigns.

"That was a really key piece," Broockman said. "It gets very far away from the quid pro quos that the court suggested are the only ways influence operates."

So if you want to figure out why the country's so screwed up these days, it seems pretty clear: follow the money. Who can actually get a meeting with a member of Congress: a group of local concerned citizens or a corporate lobbyist? And it's not the only thing reformers should be more than a little worried about. As the Washington Post notes, previous research has suggested that lobbying moves the discussion on Congress to debate over issues concerning mostly the very rich, meaning not a dime has to be spent for lower and middle class voters to go unheard.