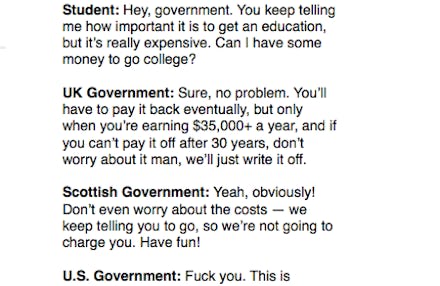

One Meme Perfectly Sums Up What it Means to Go to College in America

That about sums it up. There's a stark difference between the ways U.S. and UK students pay for college. In the UK, tuition costs are capped at a maximum of about $15,150, which doesn't need to be paid up front or until after graduation. If funded by English or Welsh funding bodies, students don't need to pay until they're earning over $35,350 and the amount owed is tailored to their income. Someone earning around $50,500 would pay $1,353 yearly for their loans. If it's not paid off in 30 years, it's written off entirely. Meanwhile, tuition in Scotland is entirely free for students who study in the home country.

But in the U.S., even bankruptcy doesn't usually release students from their debt, which is nearly impossible to shrug off even in the most dire circumstances.

Image Credit: Pinterest

Just how bad are things for college students in the U.S.? The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) has issued a new report saying that the cosigner agreements used by 90% of private loans issued in 2011 are being abused by U.S. lenders, forcing many borrowers into default despite paying their loans on time.

Students in the private loan market are often forced to have someone (usually their parents) co-sign a loan agreement to ensure the loans are repaid. But if the co-signer of the loan dies or goes into bankruptcy, the loan is often put into default whether or not payments are being made on time.

The result is pretty terrible: Young people who are still struggling to make a living are forced either to pay the full balance due on their loans immediately or ruin their credit rating, which could prevent them from finding a future home, renting an apartment, getting a job or starting a business. This is all through no fault of their own and very often comes after significant, traumatic periods of time within a family.

Lenders might be concerned that the death or bankruptcy of a cosigner could sabotage the loan, but the current relationship is predatory. The CFPB identifies a number of alternatives, including assessing the borrower for the release of the cosigner, identifying a new cosigner or refinancing the loan.

The current arrangement doesn't even make business sense, with the CFPB's ombudsman noting that banks end up losing value in the long run. And while private student loans are just a $150 billion slice of the staggering $1.2 trillion in student loan debt, they generate a disproportionate amount of complaints. In short, short-term cash grabs aimed at potentially faltering accounts are jeopardizing the system as it is designed to work in practice. And frankly, even that system working as it should would fall far short of the student loan arrangements in other countries.

While the federal government continues to subsidize education, it doesn't do so in a way that's fair for the nation's students. Some relief is already available to borrowers in the form of the income-based repayment plan for public loans, which caps payments on an income-based scale as low as 10% and forgives loan debt after 25 years. But the option is under-utilized and doesn't apply to private lenders. As Think Progress noted in January, public college tuition costs came in at $62.6 billion in 2012, less than what the government spends to subsidize the cost of college through "grants, tax breaks and work-study funds," which come to around $69 billion. So it might actually make more sense to stomach the bill and provide free federally-funded college for all public system students, pairing any such legislation with built-in cost control measures. Or the federal government could implement college savings accounts at birth which come with federal matching funds, taking the pressure off of the nation's poor to afford a better life for their children.