A Troubling Trend Has Been Taking Place in Our Government Since the Late 1990s

Image Credit: The Mendoza Line

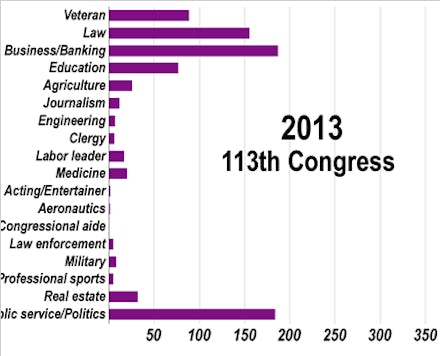

The news: Congress has a shrinking proportion of veterans and an increasing proportion of businessmen, bankers and — especially — career politicians joining its ranks. And there are still virtually no engineers, journalists or labor leaders.

The Mendoza Line observes that since 1965, "veterans serving in the House of Representatives and Senate has decreased by 64% and 68%, respectively." The Senate is doing better, but not by much.

Congress is not representative. At the exact time that the federal government is dealing with issues like net neutrality and major telecommunications mergers, Congress has virtually no technical experts. In an age of drone strikes and covert military action, there are a paltry number of journalists. And while we debate how much force should be deployed overseas on what seems like a monthly basis, fewer and fewer congressional leaders have actually served in combat.

Instead, we have leaders from business, finance and real estate at the wheel, as well as an increasing number of ambitious career politicians whose experience has almost entirely been in politics.

The background: As the Pew Research Center noted, only about a fifth of the members of Congress debating whether to intervene in Syria had any military experience themselves. Some 20 senators (20%) and 89 representatives (20.9%) are veterans.

Of course, this reflects a declining number of the population that has actually served in the military.

But considering the United States concluded the War in Iraq several years ago and is slowly wrapping up a bloody conflict in Afghanistan, the fact that few veterans of those conflicts are now serving in Congress shows our government's priorities. The people who actually fought our wars simply don't have a voice in where and when the next one will take place.

This might also explain why veterans aren't getting the respect and support they need to transition back into civilian life. Pew says "71% say most Americans know little or nothing about the problems faced by military personnel," which likely goes hand in hand with their lack of congressional representation.

Another fun little stat: For the first time, most congresspeople are millionaires. The median net worth of a member of Congress is now $1,008,767.

This is part of an upward trend that has been going on for quite some time. From the Center for Responsive Politics:

Congressmembers have always been pretty flush. But it's concerning that they keep getting wealthier at the same time as most Americans are struggling compared to a decade ago. From 2007-2010, most American families saw their net wealth drop a shocking 40%. By the way, the number of former business/banking leaders in the House of Representatives increased from 166 in 2007 to 187 in 2013 (peaking at 225 in 2009). That's right around the same time that the banking sector wrecked the economy. And the number of senators formerly in real estate skyrocketed from 18 in 1992 to 42 today, just years after the housing sector imploded.

It's probably not a coincidence that as Congress gets wealthier, they're also getting much more amenable to drastic cuts to or "restructuring" of social safety net programs like Social Security, Medicare/Medicaid, unemployment benefits and the Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program. And income inequality has reached levels not seen since the 1920s.

Basically, even as Congress continually enjoys record or near-record low approval ratings, it's getting much more plutocratic.

Career politicians: While "career politicians" are a favorite target during electoral campaigns, the term can be vague, associated with buzzwords like "D.C. insiders" and the "fat-cats in Washington." Favored by the right but also occasionally used by the left, the term implies a petty and opportunistic politician with an ambitious desire for power.

In reality, it refers to a class of people whose professional experience is entirely or almost entirely in the political arena. Their numbers have exploded this decade. And what's clear is that there's a structural problem where many members of Congress in both parties are able to stick around indefinitely without delivering legislative achievements.

As the Washington Post's Jaime Fuller noted, just eight out of 100 current senators made it to their post without being elected to a previous political office. Meanwhile, today's crop of congressional leaders have just a 13% approval rating — but they keep getting re-elected at rates 90% or higher. There's an entire field devoted to studying why Congress is stagnating.

Someone skilled at getting re-elected is not the same as someone able to pull off legislative achievements. Just look at Ted Cruz, who remains incredibly popular among Texans even after engineering a disastrous federal government shutdown in 2013.

The problem isn't career politicians per se. Rather, our electoral system is hopelessly broken and the wrong kinds of people are entering and staying in government indefinitely. Simply put, our merry band of thieves in Congress aren't capable of tackling today's issues and are increasingly beholden to special interests and big money.

A 2007 study concluded that lowering incentives for staying in politics for a long time (prohibiting former representatives from working as lobbyists, for example) and reducing the seniority advantage in elections (public finance, spending limits, etc.) would induce non-achievers to leave or not enter Congress and achievers to stick around. The achievers might actually get something done.

As Neil DeGrasse Tyson has noted, politicians who are better at arguing than delivering policy achievements aren't desirable.

Why you should care: A wealthy, stagnant Congress will have very different priorities than the average American. The rich are much less likely to believe in an activist government which would favor greater income equity, and just 43% believe that the government needs to ensure everyone has food, clothing and shelter — the absolute bare minimum standard of living.

Furthermore, the more face-time the wealthy and special interest have in our legislatures, the more congressional debate will center around their prerogatives and policy preferences. That means Congress will be spending more time debating issues of interest to the wealthy and big business and less time considering things that average Americans actually care about.