Neuroscientists Have Discovered Why Certain People Always Thrive Under Pressure

The news: There's a ticking bomb in front of you, or a huge deadline looming closer and closer before your eyes. Do you crumble under the pressure, or do you rise to the challenge as cool as a cucumber?

Though it might sound like a mental aptitude question, simple biology may explain how you react to stress differently than other people. According to a new study in the Journal of Neuroscience, researchers at the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL), a private, nonprofit institution focusing on biological research in Long Island, N.Y., have been able to identify a group of neurons in mice that determine whether they respond to stress with either resilience or defeat.

Mice with greater activity in these neurons tended to be more depressed, and became helpless. The same neurons were weak among mice who weren't bothered by added stress. Researchers believe these findings support the use of a depression treatment called deep brain stimulation (DBS), which targets these neurons.

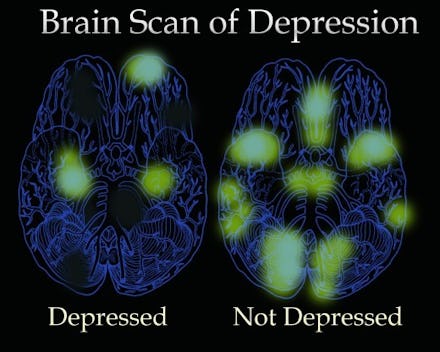

How it works: Led by Associate Professor Bo Li, the CSHL researchers examined the brain's medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), which helps to regulate emotion and behavior. And among depressed people, the area is usually hyperactive, as shown in the pictures below.

Image Credit: Bo Li/ Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory

However, until now scientists have had difficulty determining whether this activity in the mPFC triggered depression, or whether it was symptomatic of other changes in the neurons.

To see which theory was correct, researchers took a group of "depressed mice" and "resilient mice" and provided them with stress factors. Among the first group, the mPFC neurons were highly active, while among the second group, they were weak.

The results became even more interesting when the researchers took the "resilient mice" and artificially engineered them with chemical genetics to mimic neurological conditions associated with depression. "The results were remarkable: Once-strong and resilient mice became helpless, showing all of the classic signs of depression," said Li in a press release.

Why this is important: There are great implications for the study's results. With a better understanding of which areas of the brain contribute to depression, scientists can determine which treatments are most effective. "We hope that our work will make DBS even more targeted and powerful," said Li. "We are working to develop additional strategies based upon the activity of the mPFC to treat depression."

These findings will not only help researchers formulate better antidepressants, but also support the use of non-drug depression treatments such as deep brain stimulation, which can target the very neurons in question.