Scientists Just Discovered a Revolutionary Way to Treat Depression

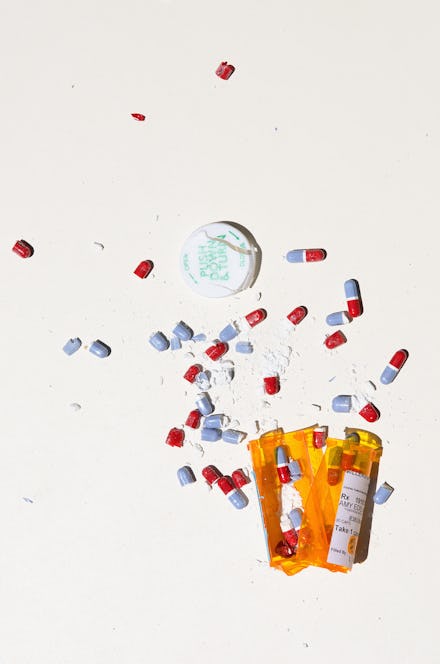

If you've ever been diagnosed with depression, you know the drill: The doctor prescribes you a pill, like Lexapro or Paxil, and tells you to come back in a few weeks.

If your symptoms improve by the time of your next doctor's visit, great. You get to stay on the medication. If not, it's time to try a new pill. Along with your prescription for one of the most common antidepressants, from Celexa (citalopram) to Zoloft (sertraline), your doctor gives you the following advice: Wait and see.

But the reality is that even the doctors who prescribe these medications — to say nothing of the companies that produce them — aren't sure how your body will respond to the drugs. Our limited knowledge of the brain means this trial-and-error process is the best system we've got.

Thankfully, researchers have just discovered a molecule that could revolutionize how we diagnose and treat depression.

The news: The new molecule is called miR-1202. It identifies people who will suffer from depression and may also be able to predict — with the greatest accuracy we've seen so far — whether or not those people will respond to current antidepressants.

Despite an overwhelming lack of knowledge about mental illness, the past few years have seen signs of progress: Schools and employers who once dismissed depression as a complaint have begun to take it seriously. A personal story about anxiety, written by Atlantic editor Scott Stossel, graced the cover of the magazine last December. And a spate of violent school shootings has prompted what verges on a real national discussion about the state of our mental health care system.

The science behind mental illness is following suit.

The details: Last fall, a group of Canadian researchers at McGill University and the University of British Columbia decided to take a closer look at the physiological effects of depression by comparing the brains of depressed people with those of people who were not depressed. What they discovered surprised them: Those who suffered from depression had measurably lower levels of a specific molecule, called miR-1202, than those who were not depressed.

The researchers then gave those with depression the antidepressant citalopram (sold under the brand name Celexa) for eight weeks and watched their brains react. In some people, the levels of miR-1202 began to increase, meaning they were starting to feel normal. Others did not respond at all. The study size was small: It included only 23 people, 14 of whom were given medication and nine of whom were controls, meaning they were given no medication. Among those who did respond to the treatment, however, reactions to the drug were far from universal. While some people's levels of miR-1202 skyrocketed in response to the antidepressant, others barely budged. The findings were published in this month's Nature Medicine.

This is a game-changer for depression treatment: By looking more closely at people's miR-1202 levels, scientists can better predict if someone with depression will respond to traditional antidepressant medications, the researchers say.

This could be groundbreaking for people who suffer from depression and have experienced the onerous process of bouncing back and forth between various prescriptions in an attempt to find one that works. If you find out, for example, that your brain will not respond to a pill, you would be free to move on to alternative treatments such as deep brain stimulation or cognitive behavioral therapy.