Racism as the monster: A history of Black horror

Tananarive Due, Black horror author, scholar, and screenwriter, on what Jordan Peele gets right about centering black stories in horror movies.

Common stereotypes about Black people in Hollywood movies can be traced back to the early nineteenth century. Black people were usually presented as either servile or monsters, and in terms of horror films, even the concept of zombies began as a metaphor for slavery.

“Look at the way voodoo and vodun were mischaracterized in early Hollywood because of this fear of Blackness, and Black power and fear of the Haitian Revolution and uprising. You have this mythology of the living dead,” says Tananarive Due, award-winning author, screenwriter, and executive producer of the documentary, Horror Noire: A History of Black Horror. “It wasn’t because they cared about Black enslavement. It was born of this idea that we're going to have the power to do to them, ironically, what they did to us. That was what zombies were in early Hollywood. So it’s fear-mongering about Black power.”

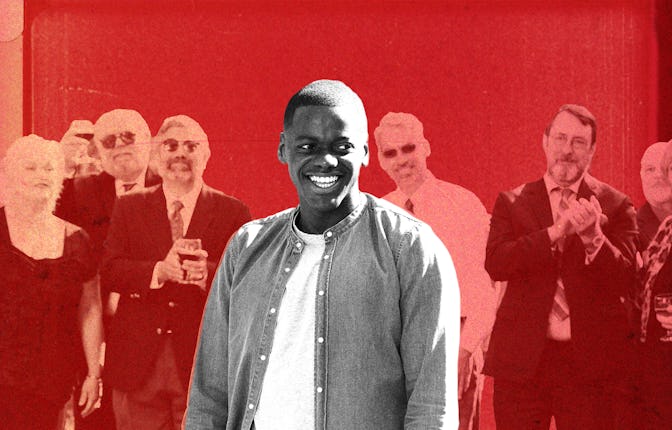

Hollywood still needs work, but it has made some progress. In 2017, Jordan Peele’s Get Out sparked a revival in Black Horror movies, with filmmakers attempting similar concepts that utilized racism as the monster. Next up for Peele is Nope, a film starring Keke Palmer, Daniel Kaluuya, and Steven Yeun, as residents of a small town who will likely deal with an alien invasion. Knowing Jordan Peele’s work in horror thus far, there’s obviously more, but it’s likely that we’re about to be schooled in how to tell scary stories that center around historically marginalized people.

Mic sat down with Due, another master of Black horror, about how Jordan Peele gets Black Horror right.

Mic: Horror Noire, the documentary, starts with Birth of a Nation as the first horror film. Talk about the historical trajectory of Blackness in horror, from Birth of a Nation to now.

Tananarive Due: I have to credit Dr. Robin R. Means Coleman for even having the vision to understand that Birth of a Nation can be considered a horror film. DW Griffith, I imagine, intended it as sort of a call to action, maybe an inspiration for white pride and white power. So, now you can see why it starts to veer into the avenue of Black horror. And yeah, it was considered art. It's still taught in film schools today for its camera angles and close-ups and wide shots. And there had never been a movie that looked like that at that time. So, this is something that is striking the arteries of the American consciousness, and where the horror propaganda part comes in, is by turning Black men — really, white actors in blackface — into monsters. It's all about Black monstrosity and the threat of Black monstrosity, at best, and Black ineptitude at worst. It's Black monstrosity to the point where Gus chases the screaming white woman off a cliff. She'd rather die than lose her virtue. And even the so-called mulatto, who tried to go through the appropriate route and asked for his white bride’s hand in marriage, ends up being a villain and the only way to stop this scourge is the rise of the Ku Klux Klan and lynching. So, this is released in an era when lynching was happening, and Black people were being dragged from their homes, whole communities were being burned over accusations, usually, having to do with Black masculinity and threatening white femininity.

That's where horror noire begins, and it’s important to note that this is not just an issue that has to do with horror movies or horror directors. This is in the DNA of Hollywood because Birth of a Nation is the birth of the contemporary blockbuster in Hollywood. It is the messaging. It’s the one to compete with, and it was the 30s before another movie was able to usurp that. So it was this long period of time when that was the message to Black people and white people. And then if it wasn't fear of Black monstrosity, it was emasculating, and defeminizing Black people. It was mammies, and coons, which has been written about well by Donald Bogle, and then we get to be the comic relief. All of this is about putting white people at ease. Even in Birth of a Nation, not all the Black men were monsters, some of them were faithful servants who would tell on the bad Black people.

And that’s how you then get the tropes of the Black friend as the sidekick, or the sacrificial negro, right?

Yes, we're here to prop you up. We're not mad about the past, we don't covet what you have. We don't wish we were you. We're just here for you. It's so comforting. And so now this is where horror gets its hands in it because that cooning is an important part of those early Hollywood horror movies. It is a pretty extraordinary journey, and there's a lot to cover in between. But now, you’re having all marginalized horror, not just Black horror, having this renaissance right now.

The Get Out effect!

In terms of cinema, I can lay that squarely at the feet of horror master Jordan Peele, whose next movie Nope is opening up [July 22]. He's so masterful in the way he does horror, especially in Get Out. The way he did racialized horror, which I think a lot of filmmakers were inspired by and aspire to, but never quite understood that Jordan Peele’s version of racialized horror does not mean lynching and I think that's a distinction. Jordan Peele’s films abide by what I call the Monkeypaw [Productions] Method, and there are three components. First of all, it's a horror movie that centers blackness. It centers a Black protagonist, a Black family, it doesn't have to center race or racism, but it centers blackness, and Jordan Peele famously said that's what he's going to be doing. Second of all, it's entertaining on the surface, but if you study it, there are layers and layers of meaning, like in most Monkeypaw films, you could really just teach a whole course on the references in that film. The third thing is that it is very careful. The Monkeypaw Method means that these films are very careful about the way they depict violence against Black people. And this is the big one, and what a lot of people who have been inspired by Jordan Peele are misunderstanding about Black horror. In Get Out, the horror was never about watching Chris get beat up, in US, it was never about watching white people whipping the family. Us is about the monster within. Candyman is about the monster within, and the monstrosity of history. In Get Out, it was white supremacy as the monster.

And I think for so many Black artists that violence rings so loudly in our personal histories and our family histories, that as soon as we get a platform we just want to shout, “This happened to us!” And I get that, but horror first and foremost is entertainment, and I think we forget that. The monster within is a great metaphor for all kinds of different horrors, but it's also universal and it's something that Black people experience. In a body horror like Candyman, you're losing your sense of self, you’re literally transforming. Body horror is universal, and it's also something that, yes, it resonates in the Black community too because our bodies attract so much unwanted attention, even when we don't want to be noticed. So, it's like a body horror when you walk into a convenience store. You're going about your day, but now you walked into the store and are Black and that's a whole different mindset. So, I really think there's a lot to learn from the Monkeypaw method. I'm very excited that Jordan Peele has a new film coming out because he really is the master instructor in this regard.

I mean, the title Nope alone is brilliant. I can't quite put it in words but saying, “nope” is the epitome of conveying Black fear or apprehension. It’s short and sweet but says a lot.

You're right about that. One of the things Jordan Peele said when he was interviewed in Horror Noire is that Black filmgoers aren’t just frustrated by the lack of representation, but by the lack of sensibilities that they would share with the characters. It’s that screaming from the audience, “Why are you even going down there!” Or, “If that were me I would…” Because part of it is a stereotype, but part of it is again, rooted in that very real history, and that genetic memory. We do hail from people who had mobs attack their homes and had to run. We do hail from people who were attacked by mobs when they tried to integrate schools, people who were kidnapped out of their homes by police and lynched, people who had to flee in the trunk of their cars. You don't have to ask too many people who are elders to try to tell you stories because you've heard at least one that was about some horror.

So, for people who have that history or who are unfortunately still living that experience of unease and insecurity, when something doesn't look right, you walk the other way, you don't walk toward it. We don't have the luxury of suburban curiosity. If I’m asking, “Hello, who's there?” You best believe I just picked up a weapon! So yeah I think it just brings overall joy and excitement for everyone when we embrace Black horror when we embrace any kind of horror that is outside of our experience. So, I'm really, really excited for the times we’re in we've been through a lot. We've been through all the tropes. We were the sacrificial negro, we've been the first to die, we've been the magical negro, we've been the sassy friend, but now we're moving beyond tropes to actual leadership In horror, and creativity, originality, and leadership in how you can translate trauma to entertainment.