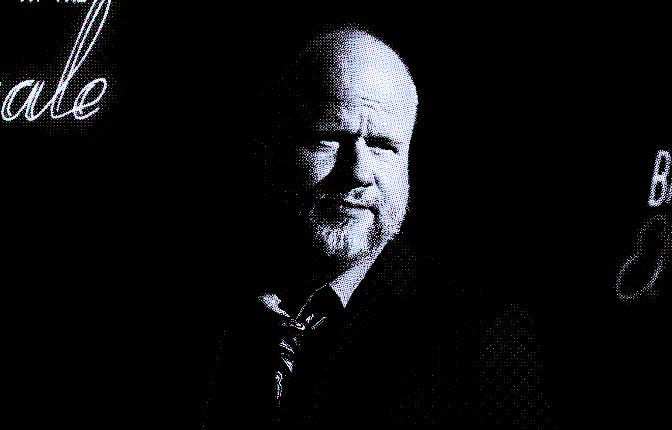

Joss Whedon can't help but tell on himself

A new interview reveals — at times via Whedon’s own words — just how terrible the once-beloved filmmaker was.

Joss Whedon is here to explain himself, even if that means making things much, much worse. In a recent feature for New York, Whedon sat down to address the wave of allegations in the last couple years that have turned him from a once beloved filmmaker and show runner, whose esteemed reputation was staked on his feminist bona fides, to instead a Hollywood pariah outed for a pattern of tyrannical and questionable behavior behind the scenes.

Yet, if the story initially seems to set up a sympathetic and nuanced portrait of Whedon, it is only to build a platform for the prolific creator to elaborately dig himself further into a hole. The story, which reports on the accounts of many of his past collaborators, is filled with a litany of not only allegations of Whedon’s dubious and even abusive behavior, but also his own bizarre excuses and defenses in response to the accusations.

“It took me a long time to realize I was writing about me, and that my feeling of powerlessness and constant anxiety was at the heart of everything,” Whedon said in the story about his inspiration for Buffy the Vampire Slayer, the iconic television show that was lauded at the time for its radical portrayal of a strong female protagonist.

This version of Whedon — essentially, that a somewhat unstable childhood made him a loner who was unequipped to manage his power as a worshipped celebrity showrunner — that he attempts to construct as a reason for his troubled actions only reveal him as a deluded manipulator. In his explanation, for instance, for his extramarital affairs (in 2017, Whedon’s ex-wife Kai Cole wrote publicly about Whedon’s cheating and how he weaponized a fake feminist persona, the first crack in the dam of his cult of personality) with young women, including actresses on his productions, Whedon offered this:

“‘I feel fucking terrible about them,’ he said. When I pressed him on why, he noted ‘it messes up the power dynamic,’ but he didn’t expand on that thought. Instead, he quickly added that he had felt he ‘had’ to sleep with them, that he was ‘powerless’ to resist. I laughed. ‘I’m not actually joking,’ he said. He had been surrounded by beautiful young women — the sort of women who had ignored him when he was younger — and he feared if he didn’t have sex with them, he would ‘always regret it.’”

Those affairs would lead to scenes like the one a “high-level member of the Buffy production team” recounts in the piece: One day, he and one of the actresses came into her office while she was working. She heard a noise behind her. They were rolling around on the floor, making out. “They would bang into my chair,” she said. “How can you concentrate? It was gross.” This happened more than once, she said. In perhaps the most chilling detail, after a closed-door, one-on-one meeting that left then-16-year old actress Michelle Trachtenberg “shaken” (Trachtenberg did not elaborate on specifics), a rule was apparently instituted that Whedon could never be allowed alone in a room with the teenage star.

If Whedon sees his younger self as afflicted with a sense of powerlessness, accounts of his on-set behavior as he became a powerful and prolific showrunner — at one point, he was also helming the shows Angel and Firefly, alongside Buffy — paint him as exceedingly cruel, and even physically harmful. In one instance, costume designer Cynthia Bergstrom recalls a time when Whedon and Sarah Michelle Gellar, the star of Buffy, disagreed about wardrobe for a particular episode. When Bergstrom attempted to move things along, “he grabbed my arm and dug in his fingers until his fingernails imprinted the skin and I said, ‘You’re hurting me.’”

In another instance, a writer on Firefly recalls when Whedon gathered everyone around after reading another one of the writer’s scripts. “‘It was basically 90 minutes of vicious mockery,” the writer said. “Joss pretended to have a slide projector, and he read her dialogue out loud and pretended he was giving a lecture on terrible writing as he went through the “slides” and made funny voices — funny for him.’”

In response to each of these damning accounts — including the already public ones, from actress Charisma Carpenter’s accusations of his vindictive behavior, particularly after she became pregnant, and Gal Gadot and Ray Fisher’s complaints of his behavior on the set of Justice League — Whedon was largely dismissive or ostensibly confused. His strongest words came against Fisher, who has publicly spoken about Whedon’s questionable treatment of people of color in the his cut of Justice League: “We’re talking about a malevolent force. We’re talking about a bad actor in both senses.”

At no point, does Whedon express any real sense of remorse or regret — if anything he sees himself as a victim. “Maybe the problem was he’d been too nice, he said. He’d wanted people to love him, which meant when he was direct, people thought he was harsh,” writer Lila Shapiro writes in the piece. “In any case, he’d decided he was done worrying about all that. People had been using ‘every weaponizable word of the modern era to make it seem like I was an abusive monster,’ he said. ‘I think I’m one of the nicer showrunners that’s ever been.’”

The story, in its initial framing of Whedon and the complex PTSD from childhood that he said he has been unpacking throughout this period, ultimately serves to subvert and expose the playbook of many a sympathetic Hollywood comeback story. In Whedon’s own words, he has in fact done very little listening and very little learning.

“People like Joss offset their trauma on other people in exchange for their energy, and take their energy to keep going — to keep themselves alive, almost,” a television writer who was 23 when she began a relationship with the then-49-year old Whedon said. “That’s why he’s so good at the vampire narrative.”