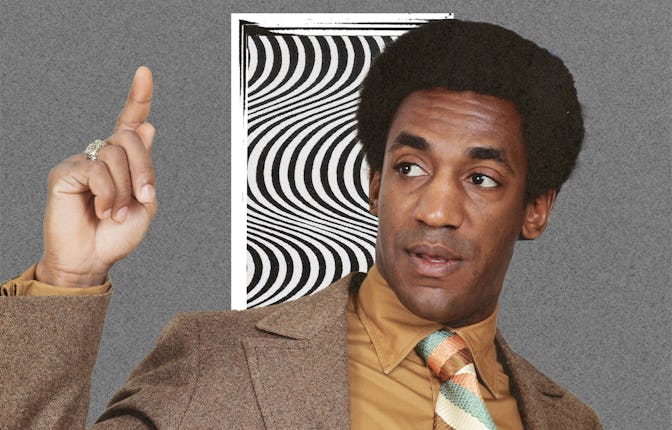

The new Bill Cosby docuseries holds up a scathing mirror to America

W. Kamau Bell’s four-part series makes it clear how much audiences refused to see about “America’s Dad.”

The title of Showtime’s We Need To Talk About Cosby docuseries is an insistent nudge to do what we’ve avoided for way too long. We’ve litigated Cosby, resulting in a brief prison stint before the complicated loopholes of the legal system freed him. We’ve protested Cosby, which has helped to raise awareness of the severity of sexual assault — but also served to divide us as a country, to a degree. But, to sit down and actually talk about Bill Cosby requires us to collectively come together and come to terms with who Bill Cosby is, a talk that will invariably lead to us discussing what he means to us. For four excruciatingly critical hours, the W. Kamau Bell-directed four-part docuseries has that tough conversation. It dissects Cosby from every angle, leading us to lose parts of ourselves in the process.

The docuseries pairs testimonials from Cosby’s rape victims, culture critics, fellow comedians, and others with re-examinations of archival footage of Cosby’s rise and demise, all to paint the most comprehensive picture of his stratospheric career and terrifying exploits. If you’re a rape survivor, the detailed recollections from Cosby’s victims are triggering. If you grew up seeing Cosby as America’s dad, you may feel like an unwitting enabler of a monster. In footage from the final episode of the series, Bell admitted that he almost quit making it in order to preserve the image of Cosby he grew up with. But by the end of We Need To Talk About Cosby, it becomes glaringly obvious we can’t talk about Cosby without having the tough talk about America.

At his peak, Cosby was more of a symbol than a man, and We Need To Talk About Cosby excellently explains how the former shielded the latter from criticism. Cosby was the first Black person to have a lead role on a major TV drama, as spy Alexander “Scotty” Scott on the 1960s hit series iSpy. For people like Temple University professor Marc Lamont Hill, Cosby’s presence on the 1970s educational program Picture Perfect was “the first Black teacher we saw,” he says in the docuseries. And as Bell points out, The Cosby Show’s depiction of an affluent Black family on a television giant NBC resolved tensions between the contrasting images of Blacks in poverty and images of thriving Black entertainers. We Need To Talk About Cosby makes the argument Cosby was protected from any inquisition into his behavior because the world — especially Black people — was too enamored with the progress he was catalyzing to tear him down.

And looking back, we can clearly see that some of that behavior was reflected in the show we all loved. For many Black people, Cosby’s portrayal of a successful Black doctor was so inspirational that, as We Need To Talk points out, we overlooked the fact that the character was an OBGYN who met with his female patients in the basement of his townhouse. We all laughed at the episode where Cosby made his special barbecue sauce that caused everyone to become, as he described it, “huggy buggy,” overlooking the fact that we were watching a character essentially drugging people into intimacy. Revisiting those aspects of The Cosby Show makes the We Need To Talk viewing experience more engrossing than a documentary simply preaching a stance; it forces viewers to ask ourselves how we missed these things — or if we just didn’t care enough to question them.

When the allegations of Cosby’s wrongdoing poured in following Hannibal Buress’s scathing 2014 stand-up routine in which the comedian shed renewed light on the issue, swarms of fans were simply unwilling to alter the vision of Cosby they had already intertwined with their memories and sense of self. “We as the public have a civic duty to back a man that gave and taught us so much,” one such defender, Crystal Lambert, told Vice in 2016. In 2014, Jill Scott tweeted that she didn’t believe the allegations because she felt they were attempts “to destroy a magnificent legacy.” And in 2018, Akon said he couldn’t view Cosby as the person who committed these offenses because he “grew up as a child looking up to this man.” While Cosby’s defenders had varied reasons for supporting the star, those reasons were all primarily rooted in an unwillingness to erase parts of themselves they had forever tied to Cosby’s on-screen and public persona.

The docuseries could’ve easily painted any present adulation of Cosby’s past work as supporting Cosby the abuser, but it instead shows the complexity in disavowing Cosby completely. People like Marc Lamont Hill, The Atlantic journalist Jemele Hill, comedian Godfrey, and Boston Globe associate editor Renée Graham are all vehemently critical of Cosby throughout the four-part docuseries — but that criticism is juxtaposed with clips of them rewatching old The Cosby Show videos, smiling instinctively. Bell’s decision to include those moments makes the viewing experience reflective, as those same smiles will likely cross the faces of viewers who can recite those scenes line-for-line themselves. Watching these interviewees, you can almost see the battle between each person’s brain (which registers Cosby as a reprehensible monster) and their heart (which still has fond memories of Cosby) play out in their facial expressions. Those small moments are crucial in depicting the issue of Cosby in all of its complexity — especially when juxtaposed by the joyless response of Cosby accuser Linda Kirkpatrick watching the same videos. Such nuanced conversations are missing from most of the discourse surrounding Cosby’s sexual predation, and they make We Need To Talk About Cosby required viewing for anyone who truly wants to understand the context beyond the controversy.

Where the docuseries falters, though, is in its lack of opinions about Cosby’s career. While the interviewees give erudite and riveting insights, few of them are Cosby’s actual professional contemporaries. Outside of a small number of The Cosby Show cast members, no one who came up in Hollywood at the same time as Cosby speaks directly to what the man was like behind closed doors for the first 30 years of his career. Phylicia Rashad, who played Claire Huxtable on The Cosby Show, has openly supported Cosby amid the allegations — and given that so much of Cosby is predicated on his elevation of the Black family on mainstream television, that idyllic matriarch would’ve been valuable to the conversation.

The same is true for Cosby’s comedy contemporaries. There has been a reckoning in the comedy world ever since Buress’s infamous 2014 stand-up, with accusations against Louis C.K., Aziz Ansari, Chris D'Elia, Bryan Callen, and many more bringing comedy’s dark side to light. The documentary features a starling exchange between Jerry Seinfeld and Stephen Colbert from a September 2017 episode of The Late Show With Stephen Colbert, two years after 35 of Cosby’s accusers graced the July 27, 2015, cover of The New Yorker. Colbert says he can’t separate Cosby the comedian from Cosby the abuser, to which Seinfeld responds with shock, as if he’s surprised a comedian’s jokes are inextricable from their personal life. This would have been an ideal time for Bell to delve into the comedian culture that would make Seinfeld unwilling to change his view on Cosby’s art, even after the latter was revealed to be a predator. Given the fact that Cosby’s sexual abuse is depicted in the docuseries as being a widely known rumor in comedy circles, omitting that community’s exaltation of his untouchable status makes the doc feel incomplete.

Still, We Need To Talk About Cosby explores Cosby’s disgraced legacy so diligently that reconciling the public image with the private misdeeds is less inconceivable. Sex therapist Sonalee Rashatwar makes a stirring point when she implies that separating the view of Cosby as America’s dad from that of the once-convicted serial rapist is futile, because rape is as much a part of American manhood as the wholesome image that Cosby portrayed on-screen. After all, in the immediate wake of Cosby’s reckoning, we saw the impacts of our ingrained rape culture at play when legendary comedian Damon Wayans went on the nationally syndicated radio show The Breakfast Club and publicly called Cosby’s victims “un-rape-able” because they interacted with Cosby after the sexual assaults. And that was far from the lone example. It’s hard to not see Cosby as a symptom of a larger problem in America when Brett Kavanaugh can become a Supreme Court justice, even after Christine Blasey Ford testified on national television about being sexually assaulted by the man. Through things like archival images of alleged aphrodisiac drug Spanish Fly being advertised to children in the back of comic books in the 1960s and archival footage of Barbara Walters being sexualized on national TV by venerable broadcaster Hugh Downs, the docuseries excels at showing how dissecting Cosby is impossible without also dissecting an American culture we’ve all been shaped by.

We Need To Talk About Cosby shows that as long as America values influence over women’s lives, there will always be a Bill Cosby lurking — and sadly enough, we’ll probably all welcome them into our homes and our hearts.