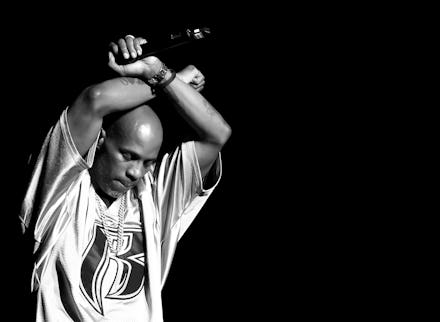

Whether in the neighborhood or onstage, DMX made us feel seen

I first found out about DMX falling into a coma last Saturday, April 3.

My immediate family had gathered at my mother’s house for the first time in a year to celebrate her birthday. Most of us had been vaccinated, which gave us something to be optimistic about. It was a good day until I discovered the unfortunate update that evening. As soon as I heard the news, I wandered into my childhood bedroom and looked around. The walls are covered with posters mainly featuring late '90s Black pop culture icons. My eyes connected with the poster of DMX holding two pit bulls on leashes. It’s one of my favorite photos of him. I stared at it and smiled. DMX’s image was positioned next to a crop of other posters, including the cover of Jay-Z’s Vol. 2: Hard Knock Life album, Mya, Silkk the Shocker, Dru Hill, and more. Being a teenager in 1998 was a good time for hip-hop and R&B lovers.

DMX first came on my radar when “Get At Me Dog” started making the rounds on the radio in early ‘98. My friend and neighborhood dance school partner came to my house, excited because she choreographed a dance to what she described as a new song that sounded like nothing she had ever heard. She recorded part of it on cassette tape off the radio (yes, I’m ancient), but before she popped the tape in, she started trying to explain DMX’s gravelly voice, his staccato cadence, and his dog growls. When she played the song, I was just as enthralled as she was. We didn’t know his name yet (she missed that part before she managed to start recording), but we made a pact to listen to the radio as much as we could until we could find out more.

We learned quickly who DMX was, and fell in love. There was the obvious: lyrics that almost always made you want to run that back because he said something so wild you had to double check what you heard. But we also loved him because he revealed his spiritual side. At the end of his debut album, It’s Dark and Hell Is Hot, he left us with a prayer, a trend he would continue on subsequent releases. It wasn’t surprising that he was a man of faith; it was startling that he was so candid and vulnerable about it.

I come to you hungry and tired, you give food and let me sleep/I come to you weak, you give strength and that's deep/You called me a sheep, and lead me to green pastures/Only asking that I keep the focus, in between the chapters.

Other MCs may have thanked God in the liner notes of albums back then, but no one was putting actual recorded prayers on albums unless they were gospel rappers. However, DMX stood before us and presented himself — during a time when hip-hop had gotten gimmicky — as a tortured soul who, moments earlier, was rapping about robbing, stealing, and battling the literal devil. He wanted to be a better man. In both songs and interviews, he shared his struggles with dark, depressing thoughts. He told us about trauma from childhood abuse and neglect, and his struggles with drug addiction, before being open about such things was commonplace in music and pop culture. Even if you weren’t religious, you understood the messaging of a human who wanted to live a positive life, even when it may have been hard.

Despite his stardom, he still rolled through on the block back in the late '90s, often in Harlem (probably in Yonkers too), near where I spent most of my childhood and where he met “Tamika from 25th.” I saw him frequently back then. Whenever he had time, he’d just come and kick it with the hood. Sometimes he’d show up alone, usually in a luxury vehicle, dressed in jeans and a white t-shirt, and sometimes he’d show up with the Ruff Ryders on their bikes. He showed love to everyone who spoke, waved, or gave him dap. I always told myself that I’d get that poster of mine autographed because he made everyone feel comfortable enough to approach him. My plan was to bring it with me every single time I had dance class, which was about three times a week. DMX appearances were common whenever the weather was nice, but also unpredictable — he obviously had a lot of work obligations, so you never knew when he would come back. I kept forgetting to take my poster with me, occasionally even talking myself out of bringing it, only to kick myself after seeing him again.

Then, one weeknight, I finally remembered to bring my poster with me. My friend’s father usually dropped me off at home after dance practice. Sometimes, when it was nice out, he’d drive us around to get food or ice cream. He was popular, always running into people he knew. One day, we were driving further uptown after practice at about 6:00 p.m., while it was still daylight outside. Not only did we spot DMX on the block, but he happened to be talking to my friend’s pop’s actual friend. That was our in, so he pulled up and initiated the rounds of daps and what’s goods (because New York) that followed. My friend and I were in a frenzy: at that time, you couldn’t tell us that X wasn’t one of the best rappers ever (still is), and here he was, being sociable and making it a point to greet everyone in the car. We had a moment where we locked eyes after all the hellos were said and done. He smiled and growled a friendly growl in a way that only DMX could pull off.

Then, my friend asked if I was going to give him the poster and ask for his autograph. Admittedly, I was shook. As down to Earth as he was, I still couldn’t believe that I was interacting with this genius who is on a poster on my bedroom wall. I was a high school kid who had dreams of interviewing people like him but at that time, sometimes even still, I often shrunk myself and wanted to be invisible in my teen angst, yet he saw me anyway. It felt like he was looking through me, as corny as that sounds. So in the end, I bombed on asking for his autograph, but in hindsight, I’m glad I got to live in the moment. At that time, I told myself that I’d see him again and that someday, I would get to work with him.

While I did end up working in the industry as an entertainment journalist, we never directly crossed paths again. I do have a funny story about a co-worker of mine at a hip-hop magazine who did a legendary interview with him but accidentally didn’t record it. It was 2008, and Barack Obama was on his first presidential campaign trail. Said coworker and I shared a cubicle, and I remember her cracking up because the name Barack Obama was new to DMX, so he turned the interview around on her, asking, “What the fuck is a Barack Obama?” Later, when she reached back out to set up another interview, he told her it was God’s will that the first one didn’t record. It all worked out eventually, but I digress because that’s her story to tell.

I’m glad I still have that poster, though. It reminds me of simpler, happier times and less of the fact that sometimes our heroes die, and that so many of them seem to be dying lately.

He did not know me from a can of paint, but he felt so familiar. Seeing him as often as I did on 125th Street and elsewhere around West Harlem, as if he were one of us, gave those of us in that neighborhood an opportunity to interact with him on a level that went beyond his visceral darkness. In a neglected place where some of the residents experienced similar pain to his, we felt like we mattered because we were touched by his light. He recognized our humanity and inspired us: if he could win, so could we.

I saw in him my father, a sensitive soul armed in bellicose bravado. Who also endured childhood trauma but found professional success, yet struggled with addiction in a similar spiritual battle that juxtaposed darkness with light. The darkness made him do questionable things, but the light would ground him, gave him the emotional intelligence enough to want to be better, and it also attracted people to him in his moments of clarity. I saw in him the talented actor, the poet, the icon, the pastor, the father, the goof, and the men on the block. Earl Simmons, DMX, gave us moments for a lifetime.

There were the spontaneous moments where he’d break out in song and dance. Like when he gave us the all-time greatest rendition of “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer,” or when he grooved to Lisa Lisa’s “I Wonder If I Take You Home” backstage while watching her perform, or when singing “Fame” while on a private jet with Swizz Beatz.

If you don’t know the lyrics to “Fame,” the part that DMX was singing in Swizz’s video went:

I feel it coming together /People will see me and cry /I'm gonna make it to heaven/Light up the sky like a flame I'm gonna live forever/Baby remember my name.

In other words, he did what he came here to do. He gave us joy, pain, faith, and good times. His time here was short, but we will always remember how he touched our lives.

This is a hard loss, especially in a time when we’re losing so many luminaries back-to-back. DMX cried with us when Aaliyah died in 2001, and ironically, the same poem he wrote for her can be said for him.

To quote DMX: “I have trouble accepting the fact that you’re gone, so I won’t. It will be like we’re not seeing each other for a while.”

Perhaps they’ve reunited. I hope he has found the peace that evaded him in life. He gifted us with a lot to reflect on, and for that I am grateful.