Facebook is sticking to its stance on deepfakes, even when they involve Mark Zuckerberg

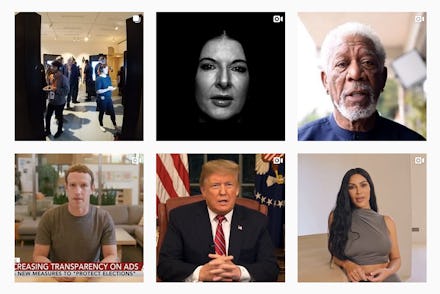

Over the last two weeks, visual artists Bill Posters and Daniel Howe have been uploading videos on Instagram that appear to show Kim Kardashian, President Donald Trump, Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg and others singing the praises of their art project Spectre. The videos aren't real. They are deepfakes, videos that have been digitally altered, often to make it appear as though a person is doing or saying something they haven't.

"Spectre is examining the power of technology and its implications on our privacy and democracies," Posters tells Mic about the project. "With no external oversight, transparency, or regulation, we are all left to the mercy of Facebook's publication policies — this is the core of the issue." He explains the project was designed to get people to think more about the "power of technology and its implications on our privacy and democracies" and help decide if we are "comfortable with so much intimate private data about ourselves being surveilled, sold, traded and used to predict our behaviors and influence our decision making."

Faced with one of its first high-profile opportunities to remove deepfake content, Facebook stood down. The company has allowed the videos to remain up and said that it plans to treat them the same way it treats any form of misinformation on its platform. "If third-party fact-checkers mark it as false, we will filter it from Instagram’s recommendation surfaces like Explore and hashtag pages,” an Instagram spokesperson told TechCrunch this week. At the time of publication, no fact check has appeared alongside the video alerting users that the content isn't authentic. The videos also appear to be discoverable on hashtag pages and through search.

To Facebook's credit, its decision shows consistency in how the company plans to handle this type of content. The company took heat earlier this year when it chose not to remove a digitally manipulated video of House Speaker Nancy Pelosi that made it appear as though she was inebriated. After the video had been shared and viewed millions of times, the company decided to severely limit its ability to spread through the news feed and added warning text alerting users that the video was edited.

The Pelosi video was considerably more crude than the deepfakes posted by Posters and Howe — though the voices used in the artists' content also serve as pretty clear giveaways that there is something off about the videos — but shows that Facebook has effectively settled on what its policy is when it comes to deepfakes and other manipulated videos: the content will stay up and, if prodded enough, the company will take action to stifle its virality.

What isn't clear is if this is the correct strategy. For the time being, deepfakes are still more of a novelty than a threat and often crop up more as proof-of-concept rather than something that truly just shows up in the wild without explanation. But with a presidential election just around the corner, there's plenty of fear that the misinformation campaigns of 2016 may deepen if fake news articles turn into believable video footage of people saying and doing things that they never would.

Omer Ben-Ami, the co-founder of Canny AI — the company that produced the deepfake videos for the Spectre project — told the Washington Post that deepfakes will be "somewhat undetectable" in the near future. “If a small company like us can do something that means governments can probably do better and people should know about this.”

The government seems particularly worried about the potential of deepfakes to disrupt and potentially forever alter the national discourse. As part of a worldwide threat assessment issued earlier this year, United States Director of National Intelligence Dan Coats warned that deepfakes will likely play a role in the 2020 election and beyond. He warned that adversaries are expected to use the technology to "augment influence campaigns directed against the United States and our allies and partners."

Likewise, Rep. Adam Schiff (D-Calif.) and other members of the House of Representatives have raised warning flags about the threats posed by the emerging technology. In a letter sent to Coats, Schiff and others said deepfake technology "could pose a threat to United States public discourse and national security, with broad and concerning implications for offensive active measures campaigns targeting the United States."

There are efforts to better identify deepfakes to quickly identify manipulated video. Hany Farid, a professor and image-forensics expert at Dartmouth College, has developed a software tool that he believes is 95 percent accurate in identifying deepfake videos. Other tools have been developed by research teams at the University at Albany, Purdue University, UC Riverside and UC Santa Barbara and others. The U.S. Defense Department has even created its own tool designed to catch deepfake videos.

However, its accuracy depends on being extensively trained on a person. As tools to create deepfakes become more readily available to amateurs and work on simpler, less powerful machines, the range of potential targets of the fake videos expand from celebrity figures to just about anyone. That also means a much wider range of potential fake content to watch out for. A politician saying something completely antithetical to their platforms can be snuffed out (though some may remain willfully ignorant to preserve a narrative that fits their worldview). Deepfakes applied to porn and other explicit material, on the other hand, could lead to a whole new branch of revenge porn in which a person is shamed for something that they have never actually done. There are already collections of deepfake porn videos depicting celebrities. Reddit recently banned communities that would create the fake videos upon request, leading to "involuntary pornography" involving everyday people.

John Villasenor, a senior fellow at the Brookings Insitute, warned that "even the best detection methods will often lag behind the most advanced creation methods." That makes the technological arms race tantamount to a game of high-tech whack-a-mole.

Given the challenges presented by deepfakes, it's incumbent upon technology platforms to develop clear strategies for addressing the content, especially as it gets more believable and potentially more destructive. Dystopian as it sounds, the videos represent a potential breaking point for our understanding of truth and could create a future in which people can truly live in information bubbles where they can see whatever it is they want to believe.

"Asking the gods of Silicon Valley to self-regulate is about as useful as asking the fossil fuel industry to prevent climate collapse," Posters says. "Only awareness, debate, and pressure for changes to the cultural norms of the influence industry and meaningful democratic oversight will begin to reform an industry that is endangering our human rights and democratic processes."

Facing down one of the biggest challenges yet in the age of digital influence, Facebook has made clear what its policy will be for now, and it seems it's to do just a little bit more than nothing.