Facebook gave Trump way lower rates on campaign ads than Biden

This article was originally published by The Markup, a nonprofit newsroom covering the ways technology is changing society. Follow them on Twitter and Facebook, and subscribe to their newsletter here.

When President Donald Trump wanted to reach out to older Arizona voters in August with the message “The RADICAL Left has taken over Joe Biden and the Democratic Party,” with photos of Bernie Sanders, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, and Ilhan Omar, Facebook charged his campaign an estimated $14 for each 1,000 times the advertisement appeared in people’s feeds.

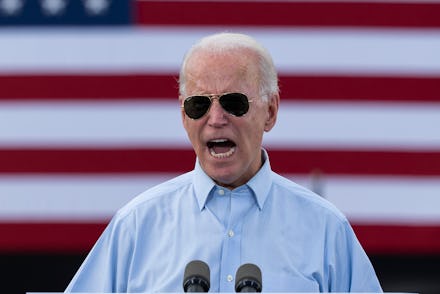

A few days later, Biden targeted that same demographic with a message of his own, that he had a plan to expand Medicare and cut drug prices. But Facebook charged him a very different price—an estimated $91 per 1,000 views of his ad, more than six times what Trump’s ad had cost.

That price difference wasn’t an anomaly. The Markup analyzed every known Trump and Biden ad purchased between July 1, 2020, and Oct. 13, 2020, and found that Facebook has charged the presidential nominees wildly varying prices for their ads, with Biden paying, on average, nearly $2.50 more per 1,000 impressions than Trump.

The difference was especially stark in advertisements aimed primarily at Facebook users in swing states in July and August, where Biden’s campaign paid an average of $34.34 per 1,000 views, more than double Trump’s average of $16.55. During that period, Biden also paid more for ads that ran nationally and in other states — an average of $28.55 to Trump’s $20.35.

Trump’s price advantage in swing states disappeared in September, when the campaigns paid roughly similar prices. In October, Facebook began charging Biden slightly less than Trump.

However, over the course of tens of thousands of advertisements placed since July, Biden’s higher average price means he has paid over $8 million more for his Facebook ads than he would have if he had been paying Trump’s average price.

The sort of differential pricing for political advertising that The Markup found would be illegal or unconventional in other media. Federal laws require TV stations to charge candidates the same price—the lowest that they charge any advertiser — for ads. Some states forbid newspaper publishers to charge one candidate a higher price.

Digital strategists and campaign finance experts worry that the obscure way that Facebook determines what price to charge could give one side a leg up.

Candidates who can figure out how to game Facebook’s ad system “get an advantage that other candidates wouldn’t get — because it’s opaque,” Ann Ravel, a former Democratic member of the Federal Election Commission and current candidate for state senate in California, told The Markup.

The Markup’s analysis is based on ads published by Facebook’s Ad Library API and provided to The Markup by the NYU Ad Observatory. To calculate the cost per mille (or cost per 1,000 views, also abbreviated CPM), we estimated the spend and impressions for each ad as the midpoint of the range reported by Facebook.

Neither presidential campaign responded to The Markup’s requests for comment.

Facebook defended its fluctuating ad pricing to The Markup. “This article reflects a misunderstanding of how digital advertising works. All ads, from all advertisers, compete fairly in the same auction. Ad pricing will vary based on the parameters set by the advertiser, such as their targeting and bid strategy,” Joe Osborne, a Facebook spokesperson, told The Markup in an emailed statement.

Osborne did not dispute any of our findings.

Effective Facebook Advertising Has Become Key to Winning Elections

Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg has estimated the platform will make $420 million on political ads this election cycle. (TV advertising for national and local races, which is much more expensive, is expected to total more than $7 billion.)

Collectively, Biden and Trump have spent $183 million on advertising on Facebook and Instagram this year, which said they would cut off selling new political ads this week as part of an effort to limit misinformation.

Facebook’s microtargeting capabilities were little more than a curiosity in 2012, but since then the platform, and its vast trove of user data, have become a major part of campaign strategy to badger core supporters for donations and target specifically crafted messages to groups of undecided voters.

“Their platform allows political campaigns to have broad reach into demographics like seniors and suburban women that are particularly valuable audiences in 2020,” Regan Opel, a former Republican political consultant who now works with progressive clients, told The Markup. She also cited Facebook’s “list matching capabilities that give us the precision needed to reach communities that have historically been under-represented in politics.”

Trump’s surprise victory in 2016 has been attributed to his campaign’s use of Facebook for raising money, energizing supporters, and “attempts to deter” Clinton supporters through microtargeted negative ads. One prominent Facebook executive said in an internal memo that Trump “ran the single best digital ad campaign I’ve ever seen from any advertiser.”

After the 2016 election, officials from both the Trump and Clinton campaigns said Trump consistently got lower prices on Facebook ads. Facebook, however, published a chart that it said showed Trump paying slightly higher prices.

Google severely restricted its microtargeting choices for political ads last year, eliminating the ability to target voters based on their political affiliation or voting record, in response to controversy over misinformation. The candidates still bought $158 million worth of ads from that company this year, according to the search and video giant’s political ads transparency reports. Those reports don’t provide sufficiently granular data to calculate CPMs, though Google uses auctions and “quality” algorithms to set prices too. (The company didn’t respond to a request for comment.)

Facebook’s Pricing Decisions Are Opaque, but Experts Say They Favor “Controversial” Content

Campaigns get charged through the same opaque, complex pricing mechanism as other advertisers, whether political or commercial: a split-second automated auction, with other factors playing a role, including subsidies for ads that an algorithm rates as more “relevant.”

The auction pits potential advertisers against one another each time a user is shown an ad, which means higher prices for ads targeting people whose attention is in greater demand.

In the thick of the campaign, voters in swing states who candidates think might be persuadable are some of the most valuable, expensive targets.

“You’re competing against every other person, there will be an overlap between who the Trump campaign and the Biden campaign and all these corporate brands are talking to,” Annie Levene, a Democratic digital campaign expert, told The Markup.

Digital strategists have made careers out of excavating the black box that is Facebook’s advertising system and gaming it to their clients’ advantage. Several told The Markup that, in their experience, the makeup of the target audience — both who is in it and how big it is — is a major factor in ad pricing.

Our analysis found instances where identical ads targeted at different audiences had very different prices.

For instance, one of Biden’s cheapest ads promised “access to affordable quality health care, for everyone” to an audience of Minnesotans in mid-September. Facebook showed it for an estimated price of $2.30 per 1,000 views.

A week later, an identical ad was shown to one-third as many Floridians but cost far more — a cost of $129 per 1,000 impressions.

Facebook charged Biden $150 per thousand impressions of a “Your prescriptions shouldn’t empty your wallet” video ad, which went to seniors, disproportionately in Florida, in early September. It was one of Biden’s most expensive.

Facebook’s algorithm also favors “relevance,” and based on predictions made by its machine-learning algorithms, subsidizes ads that Facebook considers more relevant. Relevance, as Facebook defines it, is a function of Facebook’s estimate of the rate at which people engage with the ad and Facebook’s judgment of the ad’s “quality.”

Facebook doesn’t disclose the advertiser’s target audience for the ads, nor does it disclose how its algorithms rate the ad’s relevance, so it’s impossible to say how much of an ad’s ultimate price was the product of its target audience and how much was due to subsidies by Facebook. Osborne didn’t respond to The Markup’s question as to whether Facebook has checked for algorithmic bias, political or otherwise, in its relevance algorithms.

In 2018, a Facebook executive tweeted that the benefit of the subsidies was “on the order of +/- 10%.”

But Facebook’s opacity doesn’t stop the campaigns from guessing what is inside the black box.

Eric Wilson, a Republican digital strategist, has noticed a trend. “The ads perform better if they drive more engagement and interaction on the platform,” Wilson said.

“If you’re a campaign tapping into more relevant and timely and engaging topics, which we should always read as controversial, then you’re going to get a better ad rate,” he said.

Facebook’s ad quality algorithms also analyze an ad’s content, not just users’ reactions to it. An apparent effect of these algorithms is that Facebook charges more to show liberal ads to conservative Facebook users or vice versa, compared to showing liberal content to liberals, according to a Northeastern University study.

Responding to that study, Osborne told the Washington Post last year, “Ads should be relevant to the people who see them. It’s always the case that campaigns can reach the audiences they want with the right targeting, objective and spend.”

Political Advertising Is Regulated — Just Not As Tightly on Digital Platforms

Ravel, the former member of the Federal Election Commission, said that if Facebook is favoring controversial ads — and charging less for them — “that’s problematic for our democracy.”

Some digital strategists have called for tighter regulations on advertising on digital platforms.

“That’s the real scandal of all of this. In every other industry, candidates pay the same rate. I can’t go out to a TV station and get a better rate because my ad’s better produced,” Wilson said.

For now, charging candidates different prices for online ads is legal.

“If the ad pricing mechanism is established based on [Facebook’s] own business practices, and some candidates are better at exploiting the pricing mechanism than others,” then it wouldn’t be an illegal in-kind contribution, Brendan Fischer, an attorney with nonpartisan campaign finance watchdog group Campaign Legal Center, told The Markup.

The calls for regulation go beyond price disparities in advertising. Unlike advertising on TV, ads on Facebook and Google are not subject to federal transparency laws that require disclaimers and disclosure of expenditure amounts.

Wilson, the Republican strategist, has proposed that Facebook change its rules for candidates.

He told The Markup, “Ensure that they’re paying the same amount to reach the same voters.”