No one knows what schools will be like in the fall. Here's how teachers unions are trying to prepare

Efrain Tovar has already gone through what he calls a "grieving process" — mourning the loss of his classroom, his students, the in-person student-teacher relationships he's carefully nurtured. Tovar, a middle school teacher in California's Central Valley, says that he's part teacher, counselor, mentor, and sometimes, a "surrogate father" to his students.

Now, he's on the other end of a video call. As the coronavirus pandemic worsened in the United States, forcing governors to close their states and local municipalities to send students home, teachers across the country have scrambled to translate their in-person curriculum to an online format. But while teachers have adapted to their new reality, their contracts still adhere to a set of existing standards. Teacher strikes have been a hot-button issue in recent years already, and with the foundation of American education shifting underfoot, it's possible that remote learning could wreak havoc on teacher unions and contracts.

Even while teachers have adapted to the new format of instruction, standards outlined in contracts are still being decided. The pandemic is upending state budgets, and many schools are directing what funds they do have toward retrofitting teachers and students with the technology required to enable remote learning. But experts worry that those efforts may lead to funding shortfalls come the new school year, worsening an already precarious financial situation.

At this point, with summer vacation looming, many school districts and unions already have their contracts for next school year written. That means that educators are looking for alternate ways to update their agreements for the current moment. Tovar tells Mic that his district and union are working on creating what's called a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) for the rest of this school year, which will set standards for things like how many hours a teacher has to spend teaching or when office hours should be held, helping educators install boundaries so they aren't expected to be available 24/7.

Prior to the pandemic, Tovar was already well-versed in using technology in the classroom. That's because he teaches computer science and digital media arts, and because many of his students are "newcomers" — students who have been living in the United States for three years or less, for whom English is a second language. His students speak six different languages, and Tovar has created a specialized curriculum that doesn't rely on typical spoken instruction. He also texts with students' parents through an app that allows each person to communicate in their fluent language.

Tovar tells Mic that his school district will be receiving a $2.4 million grant that will help purchase devices for teachers and fund an online distance learning program, among other tools, Tovar says. After all, just as some students don't have access to the computers or high-speed internet that make remote learning possible, some educators lack these resources as well.

"This is so new for many of us, and we're so hard on ourselves as teachers because we care a lot."

But while the grant might help patch things up for the remaining weeks of this year, there's little information about what the next school year will look like — and teachers want answers. "This is so new for many of us, and we're so hard on ourselves as teachers because we care a lot," Tovar says. He says he and his colleagues are taking this time to take care of their emotional, physical, and psychological needs, so that when guidance for the new school year comes out, they'll be ready to adjust to it.

And in many districts, guidance has been hard to come by at all. "We've had very little support or direction or anything. ... I feel like we're on our own," Sacramento County middle school teacher Dan McCrossen tells Mic. McCrossen teaches music, and he says he's still adjusting to sitting in front of a computer all day rather than standing in his music room. Remote teaching is bad for his back, he says, so he's asked for reimbursement for a chair he purchased with his own money to make things more comfortable. He hasn't gotten paid back yet.

McCrossen says that his union too has "stepped up" to negotiate a MOU regarding expectations during remote learning, and that the union fought in particular for a grading system that would be as fair to low-income as it is to wealthy students. Low-income students may not have the same access to the technology required to complete remote learning, so the MOU has set standards for teaching that don't penalize students and account for differences in home life. For example, some students may not have consistent WiFi or may not be getting full meals at home, both of which impact a student's ability to concentrate and learn. The MOU acknowledges these challenges and underscores the importance of "having enriching experiences for our students" instead of just "giving assignments and grading them," McCrossen says.

"To say this would be a smooth process is to completely [negate] the experience we've had with CPS."

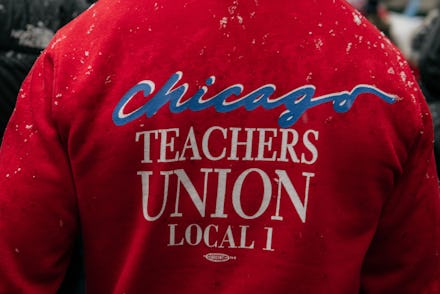

Public school teachers in Chicago, a city known for its particularly strong teachers union, are also advocating for change. The city school system's transition to remote learning was hampered by an already-acute lack of teachers, support staff, and supplies, says Chris Geovanis, director of communications for the Chicago Teachers Union. Underlying the funding challenges is the lack of transparency and collaboration from officials from Democratic Mayor Lori Lightfoot's office, Geovanis says, as well as from Chicago Public Schools (CPS), the city school district. "To say this would be a smooth process is to completely [negate] the experience we've had with CPS," she tells Mic.

The CTU struck its most recent contract with the city in October, after a lengthy and contentious teacher strike. Geovanis says that CPS is obligated to agree to learning expectations for students and work expectations for teachers, but the district is refusing to bargain on certain issues, Geovanis says.

Among the disagreements between the union and CPS leadership, per Geovanis, is that the district "unilaterally" instituted a grading system that evaluates students by when they log on to the digital learning platform and how many online assignments they complete. The catch, she explains, is that a third of CPS students don't have access to electronic devices, broadband, or both. When schools closed, these students were sent home with paper packets to complete, but only digital work will be counted under the new system, which Geovanis says is "designed to punish students who are [already] so poorly resourced."

CTU members wanted a different, non-punitive grading system that would account for income inequality and differences in home life, Geovanis says. CPS outlined the grading policy in an email to Mic, which states that students cannot receive a lower grade than their most recent third quarter grade, and that they can receive either a "pass" or an "incomplete." (Mic reached out to Lightfoot's office for comment about Geovanis's assertions but did not receive a response.)

Teaching from home has not only introduced curricular challenges, but it's also hampered teachers' ability to offer the same social support to their students without working around the clock. "What we're hearing from a lot of teachers is that they are putting as many as 16 hours a day [and] doing stuff on weekends," says Andrew Spar, the vice president of the Florida Education Association, a conglomerate of teachers unions in the state. Spar tells Mic that teachers are calling parents and kids, answering emails, and providing progress updates, all of which require hours of work outside of teaching time. Working outside of the allotted eight-hour day is unfortunately normal for teaachers, Spar says, but the pandemic has exacerbated the issue.

Spar is already looking ahead to what healthy expectations for teachers would be if schools reopen as usual next academic year. In Florida, Spar says, "18% of teachers are over 65, [have] underlying health issues, or are caring for elderly parents," so districts have to address how they'll mitigate the spread of coronavirus to protect the safety of not only their students, but their educators too. And because Florida schools are woefully underfunded, Spar is concerned teachers won't receive "appropriate protective equipment" like soap — which some teachers were purchasing with their own money even before coronavirus. "The people who work in our schools are the most caring, compassionate people you will meet," Spar says. "If they're not thinking about themselves, someone has to be looking out for their wellbeing."

The MOU that was struck in Brevard County, Florida, implements "pandemic pedagogy," Anthony S. Colucci, the president of the Brevard Federation of Teachers, tells Mic. That means teachers are expected to facilitate three hours of instruction during the school day, but they are not expected to to sit in front of their computer all day. The norms outlined in the MOU are guidelines to help keep teaching and learning in "perspective, and know what the boundaries are and aren't at this time," Colucci says. That principle extends beyond Florida, too: McCrossen's union in California used its MOU to outline how teachers should take attendance, as well as how many hours outside of teaching time they should be available to students.

"Right now the mechanism that allows people to stand together and stand up is ... the union."

But defining boundaries can be difficult when student need is high and most everyone is working on overdrive to figure out how to outfit students and teachers with the resources they need. That's why the unions are so important, says Kevin Vick, the vice president of the Colorado Education Association, the state's largest teachers union.

"If ever there was a time for a union it's now. Whenever there's uncertainty, that is when banding together is needed more than ever," Vick tells Mic. He compares the pandemic-induced financial crisis to the Great Recession, when he says that "there was a lot of acquiescence" to school district authority figures who used the economic chaos to "dictate terms of how things were going to be."

Now, 12 years later, teachers have learned how to push back. "Right now the mechanism that allows people to stand together and stand up is ... the union," Vick says.

Part of the work is ensuring that remote learning is feasible for all students, no matter their income or documentation status. Some undocumented students don't have internet access, for example, because their parents weren't able to sign up with broadband companies due to a lack of identification, Vick says. In response, teacher organizations across the state pushed internet providers to broaden the standards for installing broadband service. "There are all these barriers that are in society that you don't really think of on a day-to-day basis in terms of access — the school system is one of those areas," Vick says.

For now, this school year is almost over, and districts will have a few months of summer before students possibly return to campus. Whether they'll be able to use that time to efficiently adjust to the new educational reality in the U.S. remains to be seen.