What getting an abortion was like before 'Roe'

Mic asked three people who got illegal abortions to share their experiences — and their thoughts on the current moment.

On Jan. 22, 1973, the Supreme Court issued its decision in Roe v. Wade, effectively legalizing abortion nationwide. Before that time, abortion was illegal in many states across the country, forcing people in need of care to travel long distances or, in many cases, find an underground provider willing to perform the procedure. Those unregulated, illegal abortions were often unsafe and performed in makeshift examination rooms in apartments and other vacant, clandestine spaces. Estimates vary widely as to how many people needlessly died each year due to complications during illegal abortions before Roe, but what we do know is that once the procedure was legalized, the mortality rate fell drastically. As of 2019, with guaranteed access to legal abortions performed under a doctor's care, the mortality rate was just .041 per 100,000 abortions.

Now that the Supreme Court seems poised to overturn Roe, we are on the precipice of going back to those dark times when a basic medical procedure was stigmatized and occasionally life-threatening. Ahead of the upcoming decision, Mic asked three women who received illegal abortions in the years before Roe to share their stories and thoughts on our current moment.

***

I found out I was pregnant in January of 1966, at the start of my last semester at a Catholic university in Washington, D.C. In those days I knew nothing about birth control, but even if I did, access would have been difficult without parental approval. And that wasn’t going to come from my parents. My family was Catholic and considered premarital sex a sin. My overriding certainty was that no one — especially my parents — could ever find out I was pregnant. With that in mind, I could see no way out other than abortion. I was terrified and had no idea where to turn for help.

I searched the Yellow Pages and found a physician’s office in a part of Washington far away from my school. After a long bus ride to what felt like a foreign country I sat in the waiting room, certain that everyone knew why the little blonde girl was there. The doctor was kind and gentle when he confirmed I was pregnant. There was nothing more he could do for me.

I have blocked all memory of the actual experience except the recollection of pain, both physical and emotional.

A friend in New York City got the name of a woman who had helped other young women at her school. Arrangements were made for the procedure to be done in my friend’s apartment. The only other person I told was my roommate; I realized that I needed someone to know where I was going and why, in case something went terribly wrong.

I have blocked all memory of the actual experience except the recollection of pain, both physical and emotional. When I returned to school, I found that my roommate, unable to bear the weight of my secret, had told the dean of the college. He insisted that I meet with the priest (apparently to confess my sin) and a doctor of their choosing.

The doctor, good Catholic that he was, examined me without comment, then told me that everything was fine. His demeanor was opaque and the way he spoke vague. I thought that by saying everything was fine, he meant the abortion had succeeded. One month later, I realized he had meant that the pregnancy was still intact.

I returned to New York City where the procedure was repeated. This time when I got back to Washington I was so determined that the procedure be successful I walked around the city for three days until I felt it was safe to return to the doctor. He was very angry this time, accused me of having an abortion (which I adamantly denied), admitted me to the hospital, and insisted I call my parents while he watched.

As it turned out, the abortion had again not fully worked, and so he hooked me up to a drip designed to induce labor. It was unsuccessful, and after 24 hours he did a D&C and everything was finally over except the ordeal of facing my parents. My roommate (who had come to the hospital as a show of support, perhaps because she felt guilty at being unable to keep my secret) later told me that the doctor had informed her that my blood pressure had dropped dangerously low during the operation. The doctor’s only comment for me was to say, without emotion of any kind, that the baby had been a boy.

My parents never knew that I had an abortion. I told them it was a miscarriage, to which my mother replied, “Well, weren’t you lucky,” in her sarcastic tone. My father made me reimburse him for the hospital costs, a little at a time.

I later married but was never able to get pregnant again. I had two tubal pregnancies and a hysterectomy at the age of 30. I am certain that the abortion was the underlying cause. For years I felt I was being punished by a fearsome god for the sin of murder, and only in very recent years have I been able to forgive myself.

I regret that I couldn’t see any other way out. In a kinder, wiser society, perhaps I would have been able to give that child life. But my experience has led me to believe strongly that women must stand up for their right to make their own decisions when they become pregnant, without shame, without stigma, without fear.

- L. Keeley

“Susie, you’re pregnant,” Doc B said, leaning back in his chair and exhaling cigarette smoke. Those words, spoken flatly and nonjudgmentally by my family physician and friend, changed everything.

Until that moment in 1969, my life had been going according to plan. I’d escaped the confines of my tiny hometown in Michigan, graduated from college, and was getting ready to marry a man with a promising future. In a few months he would fulfill my dream of a house with a white picket fence, two kids, and a country club membership. Living at home with my parents that summer, I was busy planning the wedding.

Now, everything I’d been working toward my whole life was in jeopardy. I was officially pregnant, and my parents could not know. They belonged to the generation where premarital sex was a sin, getting pregnant before marriage, even worse. Sex was never openly discussed.

Later that night I broke the news to my fiancé, whom I’ll call Bob, over the phone. We agreed that when he visited in a few days we’d figure out what to do. At stake was my teaching job (the baby would arrive mid-year and the school district could easily replace me); our tiny apartment (no pets or children allowed); my dream country wedding (the invitations already sent); and my pure white, size 4 wedding dress that surely wouldn’t fit (was I even entitled to wear white?).

I’d tried sitting in a hot bath for an hour and running up and down a hill to no avail. The use of a sharp object like a knitting needle terrified me.

By the end of our discussion, we both agreed that having a baby right now was a bad idea. But what could we do? During the time since I missed my second period I’d researched how to self-abort. I’d tried sitting in a hot bath for an hour and running up and down a hill to no avail. The use of a sharp object like a knitting needle terrified me. The final alternative, an illegal abortion, seemed a remote possibility. Neither of us knew anyone who could point us to someone capable of carrying out the procedure.

Then we had a thought. A few months earlier, a young gynecologist practicing at our university’s hospital had given a presentation about the safety of the relatively new contraceptive known as “the pill.” We gave him a call and he agreed to meet with us after office hours. The three of us talked for several minutes, Bob and I listing all the reasons why we absolutely could not have a baby at this time. Then he asked me directly: “What do you want to do?”

“I want to have an abortion,” I said.

He informed us about an underground network of clergy who might be able to help. Writing down a phone number, he handed it to Bob (why didn’t he give it to me?) and said he would tell a contact person to expect Bob’s call.

The next day we learned we would have to make the three-hour drive to Chicago, where a licensed physician would perform the abortion. The cost would be $1,000 — cash.

We met our contact at a restaurant on the outskirts of downtown Chicago. Another couple was there too, an older man and a young woman. We left our cars at the restaurant and rode with the contact. The man drove us down anonymous dark streets flanked by tall buildings. The other girl looked scared. Her companion reassured her everything would be all right. The idea came to me: He has brought other women here for abortions. I suddenly felt dirty.

After driving us on a circuitous route (to throw off anyone who might be following, I think) the car turned into an alley and stopped at the back of a building.

We rode up several flights of stairs in a cramped elevator before a woman opened the door to an apartment. All the furniture inside was covered in white sheets. The woman motioned the other couple to follow her and Bob and I sat down on a sofa. When the woman returned, Bob gave her the cash. We’d planned to use it for our honeymoon in Hawaii.

I followed the woman down the hallway and into a room with a table underneath a white sheet.

The woman handed me another sheet.

“Just remove your skirt and panties. Then lie down on the table and cover yourself up.”

The woman left the room and I did as I was told.

There was a knock, and then a middle-aged, heavy set man with a mustache entered, accompanied by the woman.

“Scootch down, Hon, and put your feet in the stirrups,” the woman said.

An intense feeling of vulnerability struck me. Fighting the urge to flee, I leaned forward and tried to sit up. The woman told me to lie down and relax. Not possible, I thought.

I felt a coldness as the man wiped the inside and outside of my pelvis with alcohol. Inserting something cold and metallic, there was a prick and a sharp sting as anesthetic from an unseen needle was injected. The doctor waited a few minutes for the drug to kick in. Then it began. I felt pressure and a scraping sensation that seemed to drag on endlessly. I wondered why he didn’t simply pull the fetus out of my womb and cut the cord.

“What are you doing now?” I asked more than once.

Each time the woman said, “We’re cleaning you out.”

That didn’t sound good. I wondered if it was too old to safely abort.

The doctor said nothing, kept scraping.

I wanted to ask if it was a boy or a girl, but didn’t dare. It would have been about three months old, so I think he could tell.

Finally, it ended and the doctor left without a word. I didn’t see him again until recently when I watched a documentary about an abortion network in Chicago called The Janes. The image of the man I’d last seen between my legs, Dr. Theodore Roosevelt Mason Howard, stunned me.

***

Right on schedule, Bob and I married. I walked down the aisle on the arm of my proud father, looking the picture of innocence in my pure white, size 4 dress and Bretagne-style cap, carrying a bouquet of lilies of the valley and baby’s breath.

While my decision to have an abortion ultimately altered my plan, I replaced it with a life composed of choices — some good, some not — but mine.

A few years later my marriage ended. Before it did, I suffered three miscarriages. Were they related to the abortion? I’ll never know. Were they related to my divorce? Absolutely.

When I began writing this story I intended it to be a testimony of what it was like to have an illegal abortion, pre-Roe, and as a warning of what will happen if this ruling is repealed. Instead, it has evolved into an introspection of two questions that have pricked my brain for many years. What would she (it’s always she) have been like? And, if I’d had her, would she have saved my marriage?

The answer to the first is, of course, I’ll never know.

The answer to the second is that the marriage may have lasted for the sake of children. But there were reasons it ended, other than that Bob became frustrated by my failure to bear him children. Had I stayed married, the freedom of choice I’d enjoyed as a young woman would have been lost, and with it, my soul. So, while my decision to have an abortion ultimately altered my plan, I replaced it with a life composed of choices — some good, some not — but mine.

- Susan Quackenbush

In 1965 I dropped out of college and joined Vista, the domestic Peace Corps, a volunteer organization that sent me to a neighborhood in inner-city Baltimore.

At that point I was 19 years old and a “technical” virgin. For those of you unfamiliar with the term, it means I was sexually active, but hadn’t gone “all the way.”

I was placed in the home of a local family, an elderly couple and their 30-year-old divorced son. We often watched TV together at night. Eventually, the couple would go to bed, leaving their son and I alone with each other. One thing led to another and we began a sexual relationship.

We didn’t use precautions because he said he was sterile. I think he genuinely believed this, and I did too. But lo and behold, I skipped my period. I could just tell I was pregnant, and confirmed it with a urine test at a doctor’s office.

Panic set in.

I immediately decided I would have an abortion, which seemed like the only possible choice at the time. Unfortunately, I had no idea how to go about that. I asked around and met up with a friend who had a list of names of abortion providers she had obtained from a clergyman. Each name had certain “rules” next to it with a secret word or phrase — like saying you have a very bad cold and need to see someone soon — to let the doctor know the real reason for your call.

I found a provider on Long Island, where I grew up, and scheduled an appointment. The cost would be $500, which I didn’t have. I called my married sister, Ann, and asked her for the money. She and her husband were pretty well off, so I knew they could afford it. Ann told her husband, the jerk, who said he wouldn’t give me the money unless I told my mother.

I didn’t want to tell my mom. I’m not sure why, but it was probably because I didn’t want her to be ashamed of me. Several days later I called Ann back and lied, told her that I got my period. Hooray!

By this point, I was scared and desperate. I called several friends and asked to borrow the money. Finally, my good friend Judi came through. Her rich boyfriend gave her the money to give to me and didn’t even ask me to pay him back. A miracle!

I confirmed the appointment with Dr. S.

My cousin Betty and I took the Long Island Railroad to Amityville. I was terrified, but knew I had to go through with it.

He took us upstairs to “the operating room.”

Dr. S. met us at the station and drove us to his home. I remember him as a slovenly little old man who could have been anywhere from 60 to 80 years old. His wife was in the kitchen when we arrived and did not seem happy to see us. It wasn’t until years later that I learned he wasn’t a licensed doctor.

He took us upstairs to “the operating room.” He wanted Betty to wait outside, but I begged him to let her stay. He agreed. “It will be a good lesson for her,” he said.

While performing the procedure he said several times, “It keeps closing up.” This horrified me. I had no idea what he was talking about but it sounded like trouble. I asked him if I was okay. He said yes, it’s a good sign, I was healthy.

After he finished, he let me rest on a bed before driving us back to the train station.

I was pretty freaked out and felt sick but I had survived. I was lucky. Unlike so many people seeking abortions before Roe, I didn’t die or have permanent damage to my body.

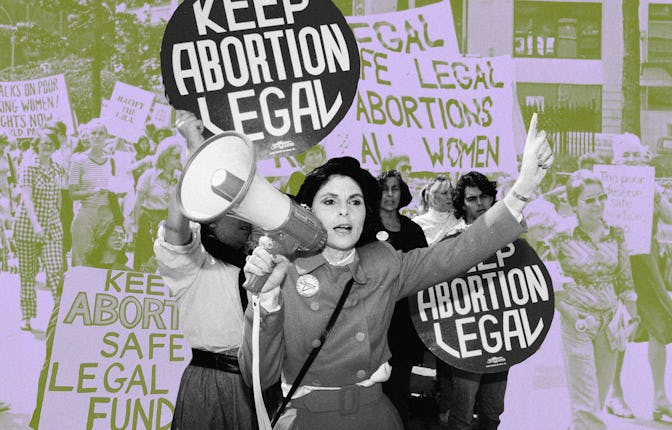

In 1979, my stepdaughter and I took the train to one of the first pro-choice rallies in D.C. There was a temporary monument to women who had died from illegal abortions. It was stunning.

With Roe on the verge of being overturned, that monument is often on my mind. It is crucial now that we remember those lives that were needlessly lost and vow to never let it happen again.

- Susan Etscovitz