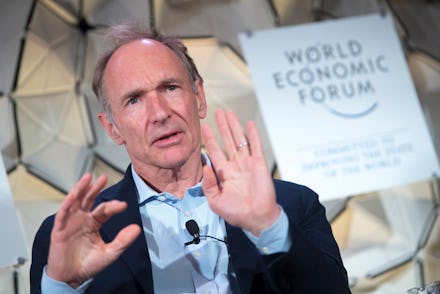

The creator of the internet has a plan to save the web

Timothy Berners-Lee is widely recognized as the man who invented the internet. Unfortunately, the web we have today is one that he barely recognizes — in part because it's come a long way over the last three decades, and in part because the world wide web has been used and manipulated by corporations in ways that no one predicted or was prepared for. Berners-Lee wants to change that. Armed with the support of tech giants including Facebook, Google and Microsoft, the inventor of the internet is using his World Wide Web Foundation to craft a “contract for the web” that would establish new ideals for how individuals, companies and governments should behave online.

Berners-Lee's contract establishes nine total principles: three for each category of internet denizen. At the top level are governments, which are obligated under the contract to ensure everyone can connect to the internet; keep all of the internet available at all times (meaning no censoring any parts of the web); and respect and protect peoples' fundamental online privacy and data rights. Companies are required to make the internet affordable and accessible to everyone; respect and protect people's privacy and personal data to build trust online; and develop technologies that support the best in humanity and challenge the worst. Finally, citizens are asked to be creators and collaborators on the Web; to build strong communities that respect civil discourse and human dignity; and to fight for the Web.

How well governments are living up to the contract

These might seem about as basic as it gets in terms of principles for an ideal internet, but every level is currently falling short of their goals. Governments have not been the advocates for free and open internet that the contract has called for. The United States may be the richest country in the world, but the government has failed to guarantee that every person has the ability to connect to the internet. The Federal Communications Commission estimates that as many as 19 million Americans lack access to fixed high-speed internet options, though other estimates place that number considerably higher. It's not just America, of course — countries all over the world fall well short of ensured internet access. The World Wide Web Foundation estimates that we won't achieve a global standard of universal access until at least 2050. Even if that goal is reached, there is no guarantee that governments follow the other principles set forth for them by the contract.

We have seen plenty of examples of governments flipping the switch on the internet when they feel it suits them. Last week, Iran's government hit the kill switch on the internet, cutting off access for most of its citizens in response to political uprisings among citizens. It isn't the first and won't be the last country to do this. Egypt's government did the same in response to political uprisings in 2011, and both Sudan and Ethiopia cut off access to quell protests just this summer. Even countries that allow the internet to operate don't guarantee unfettered access. Take China for example, which is currently blocking its citizens from visiting 157 of the top 1,000 most trafficked websites, and well over 11,000 total sites, according to analysis provided by GreatFire. As for respecting people's online privacy and data rights, most countries fall short of that, as well. The United States famously allowed its intelligence agencies to collect communications and online activities from internet companies in order to spy on its own citizens. China has been using the internet to track and monitor the activities of Uighur Muslims, a minority group living and traveling through the country who have been the victims of persecution at the hands of the Chinese government. It will likely take more than a contract drafted on goodwill to actually get these behaviors to change.

Are companies holding up their end of the bargain?

It's not just governments that fall short of the promises put forth by Berners-Lee's contract. Companies have a lot of work to do, too. Corporations that provide access to the internet certainly don't have affordability in mind when setting prices. In the U.S., for instance, most regions only have one major internet provider available, creating an effective monopoly that allows the company to charge more. It has less to do with the actual cost of the service or access and more to do with just how much the company can get away with charging. Many of these companies also fail to provide access for everyone, focusing primarily on serving profitable areas. AT&T came under fire in 2017 for essentially red-lining poor neighborhoods in Cleveland, choosing not to extend service to areas where there were more low-income families — even when they live just one block over from areas with service.

These companies will also have a considerable amount of work to do to meet build up trust with users when it comes to user privacy and data. We all know at this point that Facebook and Google are collecting our information. It's a problem so pervasive that human rights organization Amnesty International deemed it "an unprecedented danger to human rights." But it's not just those tech giants. Your own internet service provider is likely collecting your online browsing activity and selling it to advertisers. As for companies developing technologies that support "the best in humanity and challenge the worst," it's fair to say that many companies may intend to uphold this principle be fail in practice. Take YouTube, for example. Engineers there tried to create an algorithm that would drive viewers to more creators. Instead, it helped to push conspiracy theories and extremist content that has poisoned public discourse in ways that may be irreparable. Likewise, Facebook may contend that it just wants to create a place for people to connect, but has instead at times encouraged the spread of fear and misinformation. Principles like this, put forth by Berners-Lee, may prove to be too vague to enforce in any meaningful way.

How citizens of the internet are faring

As for citizens, they are likely in the best shape when it comes to the new contract for the Web. One needs to look no further than sites like Reddit or Kickstarter to find examples of people being creators and collaborators online, and millions of people have voiced their support for a free and open internet when the principles have been challenged in the past, like when the FCC undid net neutrality rules in 2017. When it comes to respecting civil discourse and human dignity, though, citizens of the Web may need some help. When it comes to conversations online, toxicity has won the day. Studies have found that discourse in comments sections and on social media have gotten worse over the last decade, and there's really not a clear path to improving that in a world where the President of the United States casually trolls his political opponents with memes and nonsense on Twitter. Trolling is one of the primary forms of discourse now, and it has led to more hateful, harmful, and divisive language in our online discourse. It would be nice if a contract could set us back on track, but it likely can't.

At the end of the day, Berners-Lee's vision for an improved internet is idealistic and hard to disagree with. But it's also largely unenforceable and incredibly vague. There's a reason that companies like Google and DuckDuckGo — one a search engine that collects all of your data and another that promises not to track you at all — have both signed on to the plan. It's because it's a feel-good measure, something that basically everyone can agree on but no one will actually be subjected to. We'll likely need much more than just a contract to fix the problems that the web is facing, but having the ideals to build off of is a nice starting point.