NASA just released the closest pictures ever taken of the Sun

On Thursday NASA and the European Space Agency (ESA) released the first images taken by the Solar Orbiter, a spacecraft functioning as a sort of paparazzo for the Sun. The mission is a collaborative project between the two agencies, with the aim of gathering more information about the star, particularly its north and south poles. The incredible images published today are currently our closest pictures of the Sun, according to NASA.

Life on Earth depends on the Sun for warmth and vivifying energy, but the star is still a huge mystery to us. Thanks to advancements in technology and space research, we now know it isn't a passive ball of plasma in the sky; it's full of constant solar activity like solar flares, solar winds, and sunspots. But astronomers don't understand what drives all this activity and how it can affect the planets in our solar system.

That's where Solar Orbiter steps in.

A chonky, two-ton spacecraft, its goal is to orbit the Sun's poles and take high quality images. On February 9 of this year, the spacecraft launched successfully from Cape Canaveral in Florida and has been controlled by crew members working remotely — a first for the team — due to coronavirus concerns.

In a visualization created by ATG medialab, and released by the ESA, the orbit of Solar Orbiter can be seen as a white trail around the Sun. Unlike the planets circling around the equator of the star, the Solar Orbiter is traveling at a slanted angle for a better view of the poles.

But why the poles? Well, we've taken multiple pictures of the Sun before, but not of the North and South poles of the star. Astronomers believe understanding the poles could be the key to unlocking the Sun's mysteries.

The recently released images of the Sun aren't pictures of the poles, but the sheer quality of these early images is enough to send scientists into an excited tizzy.

"We didn't expect such great results so early," said ESA project scientist Daniel Müller in a statement. "These images show that Solar Orbiter is off to an excellent start."

"These amazing images will help scientists piece together the Sun's atmospheric layers," added NASA project scientist Holly Gilbert, "which is important for understanding how it drives space weather near the Earth and throughout the solar system."

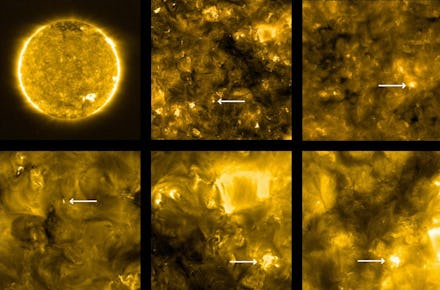

Solar Orbiter used an Extreme Ultraviolet Imager (EUI) to show sepia-tinted photos of the Sun's upper atmosphere, called the corona, that contains a temperature of over a million degrees. The details were so sharp that scientists were able to discover what looked like mini-solar flares all over the Sun.

Astrophysicist and principal investigator David Berghmans called them 'campfires' as he described them in NASA's press release. "The campfires we are talking about here are the little nephews of solar flares, at least a million, perhaps a billion times smaller," Berghmans said. "When looking at the new high resolution EUI images, they are literally everywhere we look."

The researchers noted the location of these campfires in pictures using white arrows.

The team has yet to understand what these campfires do — there's already guesses that they could be nanoflares — but they're hopeful that additional temperature data from Solar Orbiter will help narrow down the possibilities.

Another instrument on Solar Orbiter is the Solar and Helioseismic Imager (SoloHI), which produced black and white images of zodiacal light — light from the Sun that reflects off cosmic dust and can create a 'false dawn/dusk' on Earth. It's usually difficult to see this light because the brightness of the Sun hides it, but Solar Orbiter's SoloHI was able to dim the Sun to see it in pictures.

"The images produced such a perfect zodiacal light pattern, so clean," commented Russel Howard of the Naval Research Laboratory. "That gives us a lot of confidence that we will be able to see solar wind structures when we get closer to the Sun."

The last images come from Solar Orbiter's Polar and Helioseismic Imager (PHI). This instrument will measure the Sun's magnetic field, which will come in handy as the spacecraft positions into its angled orbit for a view of the Sun's poles.

"We're prepared for great science as more of the Sun's poles comes into view," PHI principal investigator Sami Solanki stated. "The magnetic structures we see at the visible surface show that PHI is receiving top-quality data."