Scientists have caught a black hole turning a star into "spaghetti"

Astronomers using telescopes positioned around the world have managed to catch a rare sighting of a star being torn to shreds as it was consumed by the powerful, gravitational pull of a black hole. A study detailing their observations was published last week in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

“The idea of a black hole 'sucking in' a nearby star sounds like science fiction,” said lead author Matt Nicholl in a statement to the European Southern Observatory. “But this is exactly what happens in a tidal disruption event.”

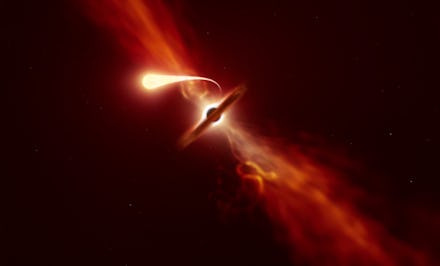

During events like these, a star that “wanders too close to a supermassive black hole in the center of a galaxy” is turned into “thin streams of material,” explained study co-author Thomas Wevers in the same release. The stringy remnants of the star has led to the process being dubbed “spaghettification.”

It’s rare to catch a supermassive black hole slurping down some star-noodles. Usually, when a star falls into a black hole, it shoots out a bunch of debris that can block the researchers’ view. But this time, the team of astronomers were able to catch the event before the debris could begin clouding the area.

“Because we caught it early, we could actually see the curtain of dust and debris being drawn up as the black hole launched a powerful outflow of material,” co-author Kate Alexander told The New York Times.

The poor victim was a star about the same size and mass as Earth’s own Sun. The black hole, however, has a mass one million times greater than the Sun, which meant the star had no chance of escaping its powerful gravity. Once the star wandered within 100 million miles to the black hole — about the same distance as the Earth from the Sun — the spaghettification began. The star was pulled into a long strand, wrapping around the black hole before draining into the center.

Researchers observed it for six months using x-ray, ultraviolet, radio, and regular optical telescopes.

“This black hole was a messy eater,” said Alexander. And it didn’t even finish its meal. Only half of the star was consumed by the black hole, while the rest was blown out as debris.

This type of observational research gives astronomers clues towards understanding how supermassive black holes behave in their environment. The team also hopes the signs they observed before the event happened could serve as indicators that other astronomers might use to tip them off to when another star will be ready for eating.