The GM strike is proof that unions are still a powerful force for change

If America’s labor unions are supposed to be dying, United Auto Workers didn’t get the memo.

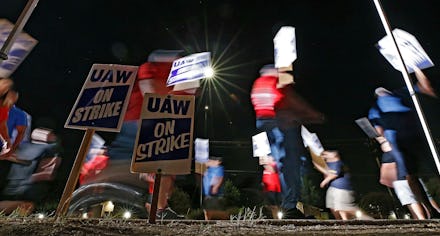

At 12:01 a.m. Monday, 49,000 UAW members walked off their jobs at General Motors after talks broke down between union representatives and management. The GM strike — which involves one of the largest unions in the country — is the latest in a series of high-profile demonstrations that have occurred across a variety of industries since 2018.

It’s a sharp departure from the devastating setbacks the labor movement endured over the past decade, including the 2018 Janus Supreme Court decision and numerous statewide right-to-work laws being passed. With its strike, UAW is demanding raises for its workers, pointing out that GM posted $8.1 billion in profits last year, as well as calling for the company to reopen plants that closed down in blue-collar cities like Lordstown, Ohio, and Hamtramck, Michigan. The automobile giant has thus far resisted these requests, claiming that it needs to instead invest more money in developing new electric car technology.

UAW is generally strike-averse; its last strike took place in 2007, and before that in 1999. According to Janice Fine, a labor professor at Rutgers University and the director of strategy at the Center for Innovation in Worker Organization, the fact that UAW members are now choosing to flex their considerable muscle is part of a larger trend of robust collective action throughout the world of organized labor. In other words, she said: “Strikes beget strikes.”

Over the past 30 years, strikes have become increasingly rare. Right-to-work legislation, which undermines organized labor by prohibiting even unionized workplaces from requiring employees to join the union and pay union dues, has decimated private sector unions across the country, and President Ronald Reagan’s decision to fire 11,000 striking air traffic controllers in 1981 left a chilling effect in the public sector. For much of the late 20th century, unions’ status as power players in American politics seemed to be on the decline.

Now, though, that trend has begun to reverse. Last year, more workers took part in strikes involving over 1,000 people than in any year since the 1980s. Fine explained that the new energy is a result of workers across industries rediscovering that strikes are an effective tool in the fight against corporate power, perhaps stemming from a series of high-profile collective action wins.

Strikes beget strikes.

“The fact that we've had almost half a million people on strike this year is an indication that more workers are feeling that they are capable of demonstrating their economic power and leverage,” Fine said. She points to the teacher strikes last year in West Virginia, Arizona, and Oklahoma as a galvanizing moment for labor. “That was a huge bottom-up movement across mostly red states,” she explained. The strikes dominated headlines — and earned their participants substantial gains.

Just as importantly, the teacher strikes established a handy rubric for future organizing by pointing out the importance of a compelling narrative, said William P. Jones, a professor of history at the University of Minnesota and vice president of the Labor and Working Class History Association.

“In places like West Virginia, they very effectively framed their strike as partially about their own economic condition, but also about the broader state of public education,” Jones explained. “They were striking for better wages, but they were also striking against budget cuts and against school closings, and I think that effectively frames their own struggles as workers in the interests of the broader public good.”

GM workers have a similar opportunity, Jones argues, to present their economic struggles in more general terms that will help them build support. The UAW members can point to the GM bailout of 2008 — in which the company received billions of dollars from the government in order to fight the recession — and claim that workers deserve to receive their fair share too. After all, their hard work has kept the company from going under and bringing the rest of the economy with it. “They can make a similar argument that the teachers made,” Jones said.

It’s not just fellow union workers who are paying attention to the new wave of strikes. The American people are too. Last year, as the teacher strikes made front-page news for weeks, public support for unions rose to a 15-year high. According to a Gallup poll from 2018, 62% of Americans feel favorable towards unions.

“What's really interesting is that support for unions crosses partisan lines. If you look at low-wage Republican workers, they feel the same way about unions as Democrats do,” Fine noted. And what’s driving this increased public support? In a word: “Inequality.” Americans are aware that, despite the strong economy, profits are not being shared equitably between workers and corporations, who have enjoyed lavish profits even as wages remain stagnant.

Add that to the fact that prominent class-conscious 2020 hopefuls like Sens. Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren have helped push labor issues to the forefront of the Democratic agenda, Jones pointed out, and you get this renewed energy behind organized labor. Even untraditional industries, like digital media, have experienced a spate of unionizations in recent years. Earlier this week, Warren earned the endorsement of the Working Families Party over Sanders, whom the party supported in 2016. The news prompted some Sanders supporters to hit back at the WFP for not releasing its vote totals — evidence of how influential the left-wing group’s endorsement is perceived to be for truly progressive candidates.

The wave of collective action isn’t slowing down any time soon. On Monday, mere hours after the GM strike began, a coalition of 80,000 union workers at Kaiser Permanente hospitals nationwide announced a strike set to begin Oct. 14, accusing the company of overpaying management and outsourcing jobs.

"We believe the only way to ensure our patients get the best care is to take this step," said Eric Jines, a radiologic technologist at Kaiser Permanente in Los Angeles, in a coalition statement. "Our goal is to get Kaiser to stop committing unfair labor practices and get back on track as the best place to work and get care. There is no reason for Kaiser to let a strike happen when it has the resources to invest in patients, communities, and workers."

While he may be speaking about Kaiser specifically, it’s easy to see how Jines’ message could be adapted for countless other corporations.