Why so many people have the exact same drug trip

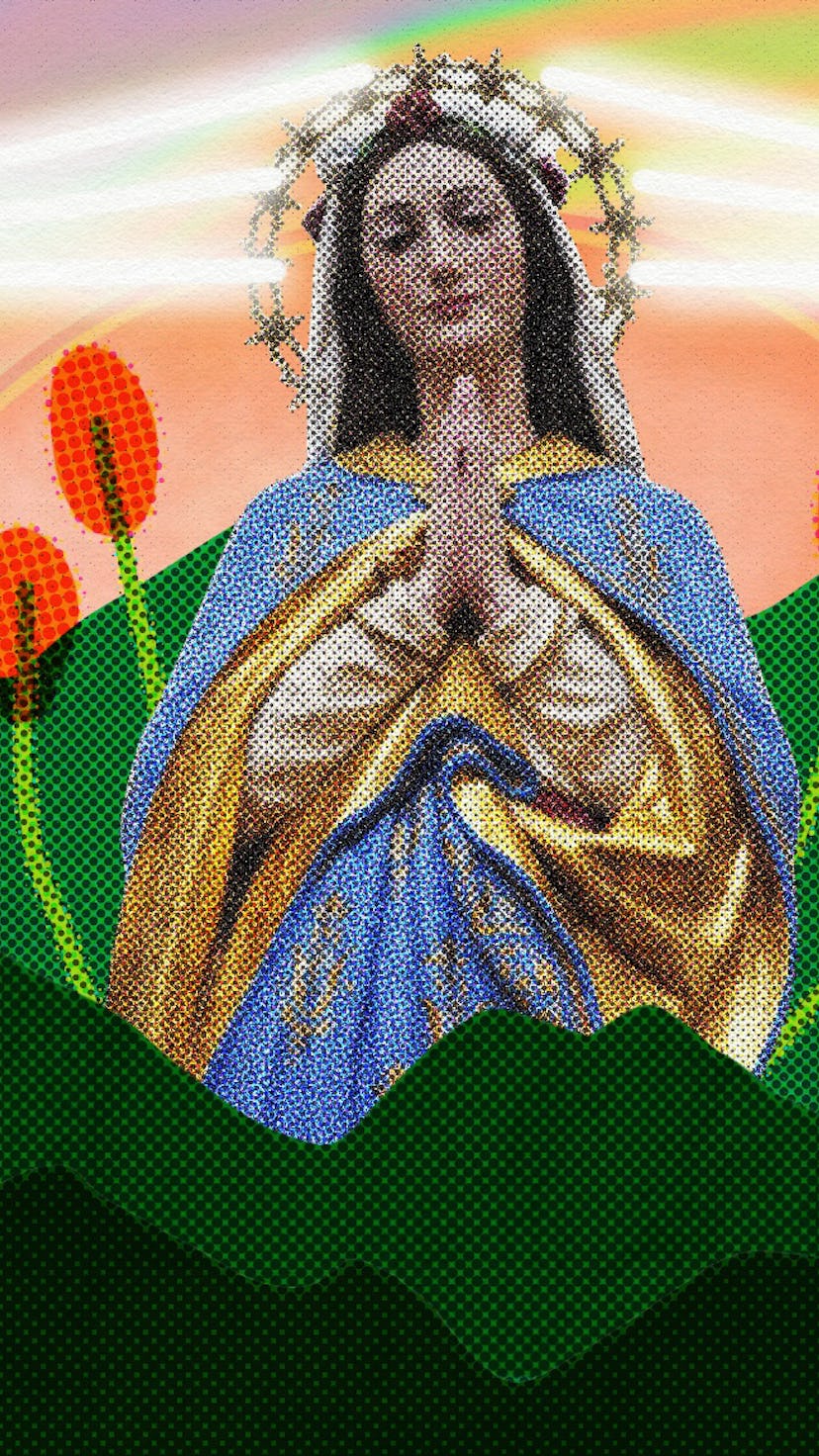

I thought I was the only one who transformed into Mary Magdalene while high.

Last year, I was under the influence of a psychedelic called iboga when God occupied the ceiling light above me and imparted some exciting news: I was going to be the “author of the next Bible,” and my current love interest and I were "Jesus and Mary Magdalene."

I knew this revelation wasn’t literal (or rational), yet I felt as if I’d been anointed as some kind of spiritual leader — only to be told by a friend a few months later that a mushroom trip had informed her she was the author of the next Bible. And then by another friend that psychedelics had led her to believe she and her boyfriend were Jesus and Mary Magdalene.

Disappointing as it was to learn that I was not the singular modern-day Mary Magdalene and Bible author, this left me fascinated about how separate people could have almost the same exact drug trip — and on different hallucinogens, at that. Turns out, I’m not the only one who’s shared a trip with someone else. There are several common themes that repeatedly come up in psychedelic trips, which can cause even people who have never met to have eerily similar experiences.

“Psychedelics disrupt the integrity of the default-mode network, a typically well integrated network of cortical brain regions that mediate our sense of self,” explains Gabrielle Agin-Liebes, a Berkeley, California-based psychologist and post-doctoral researcher at the Weill Institute for Neurosciences. “Classic serotonergic psychedelics [such as mushrooms and LSD] appear to facilitate a less constrained style of cognition and weaken this circumscribed experience of self.” In other words, psychedelics can enable you to temporarily let go of pre-existing ideas about who you are or even the world at large.

The result of this shift in brain activity is often that people experience “a feeling of universality, of oneness with things, of being able to get a higher perception — a God’s-eye view,” says James Giordano, professor of neurology and biochemistry at Georgetown Medical Center. “How they interpret the phenomenology of their experience is that they are becoming God-like.” Bingo.

This sense of transcendence may result in someone actually believing they are a religious figure, or, they may feel that some spiritual figure — usually, one prominent in their culture — is with them. For evidence of this, look no further than the multiple Reddit threads about people encountering Jesus on psychedelics.

Other times, these encounters are with nondescript spirits rather than specific cultural icons. In a 2020 study in the Journal of Psychopharmacology, 2561 people recounted encountering otherworldly presences on DMT, most commonly describing them as beings, guides, spirits, aliens, and helpers. Often, people experience such beings as “deific chaperones” — divine beings watching over them — says Giordano. This experience can be magical and comforting, regardless of what exactly is causing it.

Because psychedelics are believed to increase connectivity between the brain’s hemispheres and therefore tamp down inhibitions typically present in our perception, they can turn up our tendency to perceive things as “agentic” — i.e., possessing thoughts and feelings — and to sense other presences with us, Giordano explains. This can make it feel as if a chair, a beam of light, or a hallucinated image is sentient.

Combined with another phenomenon called pareidolia, where people see a vague outline of something and fill in details (e.g., perceiving a cloud as an animal), this can cause someone to visually hallucinate a divine entity. “It's a profound experience,” says Giordano. “They can say, ‘the chair turned into a flower, and I felt the flower had my best interests in mind and it was my guide.’”

For a mind on psychedelics, a person — including oneself — can even be perceived as a spirit of sorts. Boris Pelekh, a 40-year-old musician based in New York City, saw his neighbor in an ayahuasca ceremony as a jaguar — and learned afterward that his neighbor had “felt that through the entire journey, he was emerging into his spirit animal … a powerful cat.” It could have been the manner in which his neighbor was sitting or even the way he moved. But for Pelekh, this experience was deeply profound and spiritual.

Unfortunately, some common and shared trips may be more unsettling than joyful. Ben Witmer, a 33-year-old artist in Hawaii, was presented with the choice to live or die while on mescaline and mushrooms: “I could either continue to exist in the echo chamber void of my current experience, or I could turn it off to break through the black walls of infinity,” he recalls. “I thought that I hadn’t yet learned, created, or experienced enough to move along to whatever is next… and I quite enjoy existing! So I chose to stay.”

“We can then attune and access a deeper wisdom and knowing within us, or one’s higher self. This allows for the embracing of universal truths such as uncertainty, connection, and unity.”

Many people have trips where they’re directly (and sometimes frighteningly) confronted with death. “Over half of the participants we interviewed in one of our qualitative studies reported experiencing some type of death experience,” says Agin-Liebes. It’s important to note that this study was on cancer patients who were given psilocybin, the active ingredient in magic mushrooms, so death may have been a particularly pertinent theme for them.

These experiences are quite different than what most would consider a “bad trip” (that being said, please always trip safely, preferably with someone who has experience if you’re new to a drug). Even if they’re difficult in the moment, death-related visions can have a big payoff. “These experiences consistently led to feelings of relief and comfort, as the psilocybin gave substance and a sense of familiarity to death,” Agin-Liebes says. One of her patients reported realizing that “there is nothing to fear after you stop being in your body … you just see with your own eyes.” Another recalled traveling “deep somewhere in my subconscious,” getting “to something really close to what death would feel like.”

Since death is an inevitability for all of us, it may be that once people’s control over their own thoughts is lowered, their minds can’t help but go there, Giordano theorizes. “For a lot of people, the finite nature of their own existence sort of looms behind their subjective curtain,” he explains. “A trip parts the curtains, and it's like, ‘holy shit, I’m confronting my own death.’”

Agin-Liebes actually recommends “dying” if given the choice, because “surrendering or allowing some old identity or way of being to ‘die’ can be profoundly valuable in helping one let go of old patterns,” she explains. “We can then attune and access a deeper wisdom and knowing within us, or one’s higher self. This allows for the embracing of universal truths such as uncertainty, connection, and unity.” Some refer to this letting go as a psychological ego death — an illuminating experience that can make you feel more connected to yourself.

When people trip together, shared themes may be even more common. Daniel Saynt, a 39-year-old club owner in New York, took mushrooms with a group of people at Burning Man, then they all lay down, “deeply observing the sky together,” he recalls. “One of the guys began talking about how the lights made the clouds dance, and then about seeing God in the heavens.” Afterward, the group discussed how they’d “collectively felt the presence and could see the sky moving and opening up,” says Saynt. They also all heard “a rumbling, deep internal feeling vibration from the sky.”

Indeed, people under the influence of psychedelics can be very easily influenced, to the point that if someone is describing their trip in real time, someone with them may experience the same perceptions. A 2015 study in Psychopharmacology found that people scored higher on a suggestibility test after being given LSD.

This can actually be a positive thing when someone’s having a bad trip and needs help getting out of it. “You can have guided trips; that's one of the nice parts about tripping with people you like,” says Giordano. “If you’re going to a particular place that's problematic, they can bring you back or bring you down.”

Still, the appearance of certain themes in many people’s trips may be more than just a result of human suggestibility or the neurological effects of psychedelics. This phenomenon may, in fact, prove just how much we all have in common. “There might be universal components of psychedelic experiences, as there are in spiritual experiences,” says Agin-Liebes. While experiences of being a God or saint may not be appropriate to take literally, the feeling of oneness that we get on psychedelics may be more than an illusion.