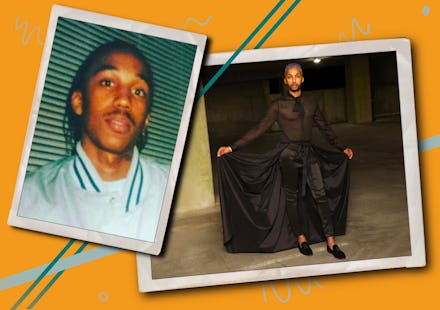

As a queer Black person, I demand a do-over for my adolescence

When I think about my childhood, I often wonder about the teenage experience I see in movies and TV: self-conscious yet carefree 16-year-olds pondering their budding identities and exploring relationships. It seems carefree, fun, and sometimes gleefully foolish. I, on the other hand, spent my teenage years in survival mode, constantly suppressing my full identity. Now in my 30s, I find myself still having “first ever” moments — ones I would have much preferred to have had in my teens if society hadn’t thwarted my first attempt.

Living a queer identity was only part of the marginalization I faced. I was already a Black child, which meant a limited opportunity to have an actual childhood. See, even as kids, we’re perceived as full grown threats to safety. As professor and author Stacey Patton succinctly put it in a Washington Post op-ed, “Black childhood is considered innately inferior, dangerous and indistinguishable from black adulthood. Black children are not afforded the same presumption of innocence as white children, especially in life-or-death situations.”

So then, when your Blackness intersects with queerness, not only are you walking around in the body of a mini menace, you are further stifled in adapting to relentless hetero norms. This combination can force young Black queer people such as myself to endure a different type of adolescence — one that can last well into adulthood.

I didn’t begin intentionally exploring my sexuality until I was nearly 21 years old. I didn’t have my first openly friends until I was almost 25. I didn’t share my identity publicly until I was 27. I didn’t identify as non-binary until I was 34 years old. I have never had a partner. At the age of 35, I am only now becoming acclimated to the capacity of romantic involvement with another person — something my heterosexual brother began exploring at 15. That decade-plus long delay means that I’m very much still learning the social and cognitive skills that go along with romantic relationships. Thankfully, I’m giving myself the grace to explore the things I never got the chance to do in my teens.

So much of our adolescent development can set the table for our matriculation into adulthood. Puberty opens Pandora’s box of body struggles. We begin our journey to autonomy, changing social groups and forming our own opinions on what’s right and wrong, independent of the most influential people in our lives: our parents. Straight kids grapple with these concepts in the context of a society built for their acceptance — leaving those like me, on different points of the sexuality spectrum, with little to no space for discovery.

When I was a teen, my moral reasoning revolved around whether it was “okay” to be queer. I had no one I felt safe enough to discuss this with. So while others explored together, I processed alone. I had no openly queer friends; most of them were girls who were dealing with their own puberty-related drama. I did have one friend who I assumed was queer, but we both were too afraid to ever say it to one another. As adults, we are now friends. And both of our stories of safety and suppression through high school are painfully similar.

Learning about sex was also a lonely road. In the 90s, many kids who even attempted to be a non-hetero couple were suspended or expelled. It’s also important to note that queerness — forget about being “accepted” — wasn’t even recognized as something “normal” until after the 70s.

Until 1973, the DSM-III (the diagnostic guide for mental illness) pathologized homosexuality, deeming it abnormal or psychologically unhealthy. There were no laws and protections in place for queer people who publicly lived in their identity. Schools had no LGBTQ-specific curriculum and even as of 2020, only two states are required to have LGBTQ history as part of their teachings. Sex education was non-existent as queer sex was not (and in many school districts, still isn’t) taught. Let’s face it: Real and useful guidance for heterosexual sex sill barely exists. This all made my exploration trial and error — with more error than trial.

I’ve crafted a career around discussing queer identity and race, especially how Black queer people living with visibility and representation are currently in our “blueprint phase”— meaning, we are constructing new “norms” for the next generation. In other words, we’re working to provide what we didn’t have ourselves, so others don’t have to “do” adolescence in their 30s. This doesn’t negate the fact that they will also be tasked with fixing where we went wrong and building upon what was given to them, as each generation before us has done.

This societal notion of full integration in our Black queer identity isn’t our problem alone. It is on non-queer people to dismantle the systems that oppress us, especially those intracommunity. We are often asked are we Black first or Queer first — another notion other groups don’t ever have to wrestle with. The duality of our adolescence stolen negates our young adult growth, often manifesting throughout our adulthood, with many Black queer people to this day NEVER living in their full identity. There are still queer people who will never feel safe enough to identify as such.

I’ve learned to give myself grace for the struggles that may appear today because of a delay I had no control over. I extend that same grace to many of my queer family while fighting to eradicate the systems that continue to steal our childhoods and adolescence. Although I see so many queer children identifying younger and younger, I fear for their safety. But I smile to see that at least some of us can know the feeling of having a semblance of adolescence, in a world hell bent on its denial.