Scientists are studying exoplanets that are “fluffy” like cotton candy

Who doesn't love cotton candy? It's colorful, sweet, and oh-so-fluffy. Apparently, it also has more in common than you might have thought with a relatively young and rare class of exoplanets, with a "puffy" density that most closely matches that of the sugary concoction. According to new data acquired by NASA's Hubble Space Telescope, scientists may now have a window into what these cotton candy exoplanets with startlingly low densities are actually comprised of. Now, after initially discovering an entire system made of exoplanets in 2012, NASA's team of astronomers is finally able to confirm what makes these strange planets so puffy.

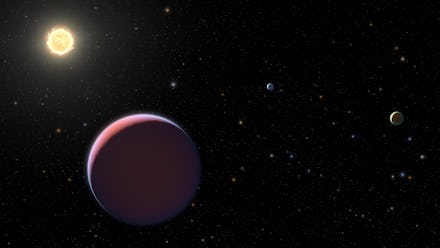

The cotton candy-like exoplanets are located in the Kepler-51 system, which features three puffy planets orbiting around a star like the Sun, originally uncovered by the Hubble Space Telescope seven years ago. But scientists weren't able to really begin studying what the planets were made of until 2014. Now, with the recent Hubble data, teams have determined that they're no more than a few times the mass of Earth with hydrogen and helium atmospheres that actually make them the size of Jupiter. There's just one huge difference: they're about a hundred times lighter than Jupiter.

It may be difficult to wrap your head around, but these planets only look enormous. The "super-puffs," as NASA called them, went under the telescope, so to speak, as scientists tried to zero in on evidence of any sort of components in the planets' atmospheres to see what makes them the way they are. What they found was a lack of chemical signatures across each exoplanet due to the clouds of particles up high in each one's atmosphere. But these clouds may not have been made of water, like on Earth. They could have been composed of salt crystals or any number of other things, making the examination process even more difficult.

"This was completely unexpected," the University of Colorado's Jessica Libby-Roberts said of the research attempt. "We had planned on observing large water absorption features, but they just weren’t there. We were clouded out!"

The team ended up drawing conclusions from the data they were able to uncover that the planets' low densities were just a result of the small system's relatively young age – just 500 million years old. That's basically a tot in comparison to the Sun, which is around 4.6 billion years old. And as the planets get closer to their smaller star as they orbit around it, their atmospheres will likely begin to evaporate, revealing the actual planets' shape underneath, though they'll still be mostly low-density anomalies.

Additional research is still in the cards as well, thanks to NASA's new James Webb Space Telescope, which is still being built. In the future, scientists may be able to glean more information about what makes these puffy exoplanets unique to begin with. Until then, we'll just have to imagine them as big balls of sugary fluff way out in the wilderness of space.