Hot Topic forever: How Gen Z revived early-2000s pop punk

It’s not like pop punk ever left. The genre, defined at first by the infusing of pop melodies and structures into punk’s anarchic ethos, has been around since the late ‘70s and early ‘80s — with Buzzcocks pioneering the sound that would lead to bands like Descendents, Screeching Weasel, and The Queers. In the ‘90s came bands like NOFX, The Offspring, Sum 41, and Blink-182. And in the early ‘00s band slike Simple Plan, Good Charlotte, All-Time Low and Fall Out Boy infused emo into their sound, and pop punk went mainstream. It was at its commercial height in the early aughts; Simple Plan’s Still Not Getting Any..., Avril Lavigne’s Under My Skin, Paramore’s Riot, My Chemical Romance’s The Black Parade, and many other classics defined the era. Blink-182’s self-titled fifth studio album — the one with “I Miss You” and “Feeling This” on it — came out sixteen years ago this November.

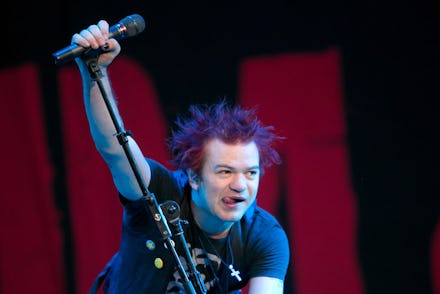

Sixteen years, apparently, makes a sound ripe for revival. The comebacks have been bubbling for some time, but now they are in full stride. Green Day, Fall Out Boy, and Weezer recently announced they’d be going on tour together. (For some reason they’re calling it the “Mega Hella Tour”... don’t ask me.) And that’s not even all. The former two bands, plus Jimmy Eat World, Dashboard Confessional, and Sum 41, are all releasing new records in the next five months.

Of course, the revival had to be preceded and fueled by nostalgia and youth interest. It started with kids like Lil Peep, the Long Island-born emo rapper Gustav Åhr. Born in 1996, Peep straddled the line between millennial and Gen Z—if he were still alive today, he’d be 22; kids his age are now just graduating college.

In a Pitchfork profile on Peep, Steven Horowitz wrote that the rapper started messing around with his hair color in middle school, influenced by My Chemical Romance's Gerard Way, “who had bleached his cropped coif for the release of 2006’s The Black Parade.” I was sixteen when that album came out, but Peep would have been just about to turn ten. He was also a fan of Good Charlotte, who tributed the late rapper with a cover of his song “Awful Things."

Lil Uzi Vert, too, has been known to take to Instagram live just to rock out to Paramore and has cited Hayley Williams as his greatest inspiration. Riot Fest even made this cute “Emo Fan’s Guide To Emo Rap.”

Blink-182, Sum 41, Third Eye Blind, and Gym Class Heroes were definitely influenced by their hip-hop contemporaries. Now, if you go on most streaming platforms and click a song at random, you’re likely to get an emo rap song. A slew of teens making sad rap tracks in their bedrooms. And then this funny thing is happening within emo rap, where it’s almost folding in on itself — or, expanding. Often emo rap tracks are tagged #AlternativeRock, sometimes #Indie, and it’s getting increasingly difficult to tell when it’s tongue-in-cheek.

To Gen Z, it seems, genre really is a construct. On an album by the Maryland emo rapper Landon Cube, for example, there are at least two actual pop songs. Artists shrimp and guardin are emo rappers, too, but they also make songs with acoustic guitars, like the latter’s “i think you’re really cool” and the former’s recent “this body means nothing to me.” And try to tell me poppy tears’ “fuck views i just want tattoos” isn’t literally just a pop punk song, or that Andy Sanborn’s “statues” doesn’t sound like Postal Service.

OCTAVIO, from Knoxville, is one of my favorite artists doing this; his music sounds like emo rap meets dream pop. And I absolutely love the mega-earnest nostalgia of 1080p dreams’ “green day in ‘94.”

“I wanna blow up like Blink in '99 / Playing on Total Request Live / Cameo in American Pie / With a monkey and that random surfer guy / Gaining millions of fans / Making fun of lame boy bands.”

Part of this genreless movement is the Florida-born musician Dominic Fike. He grew up listening to Cali-core music like Blink-182 and Jack Johnson, but started out rapping. Somewhere along the way, he pivoted to a sound akin to the music he was raised on, to something more like a scene version of Sublime or Red Hot Chili Peppers. But he maintains the SoundCloud rap look, and when he performs he draws crowds of all the coolest looking teens — the ones who dress like Hot Topic is still a thing, only they probably shop exclusively on Depop.

Even Vic Mensa now has a pop punk project, 93PUNX. There is also an entire contingent of young pop punk and emo bands. The groups Neck Deep, Waterparks, and SWMRS, are skater boy types who “sell sad songs to the ones who feel alone,” as Trophy Eyes put it, and could easily fit on a lineup with Dominic Fike. Doll Skin, a band of four young women from Arizona who cite My Chemical Romance and Avenged Sevenfold as their strongest influences, toured with New Found Glory, Real Friends, and The Early November this past summer. One very cool thing about pop punk’s resurgence is that it seems to be more inclusive than it ever was — not only to rap fusion, but to women. Stand Atlantic, Yours Truly, and December Falls are just a handful of current pop punk bands fronted by women, all exploring a wider range of emotions than their male predecessors ever did.

As Amanda Petrusich noted in her New Yorker essay about Blink-182’s return, “no era is presently being gazed upon with more pie-eyed approbation than the waning years of the twentieth century.” It’s not exactly nostalgia, she wrote, since the zoomers adopting the scene look weren’t even alive when Hot Topic actually was a thing. “[B]ut it is earnest, and it is widespread.”

There is something about the rage, pain, and despondency in this particular vein of emo and pop punk music that is speaking to an entire generation. When these bands were first coming out, they had huge followings, but weren’t exactly taken seriously. This revival wave proves their influence was stronger than anyone thought. And, as with any generation, the kids take what was misunderstood from their youth, and reinvent it — as if to say, “We’re right.”