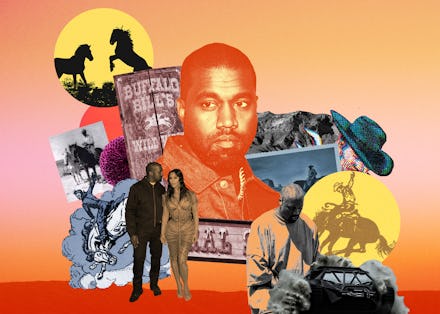

Kanye West and the dream of Black wealth in the Mountain West

In 1920s Wyoming, rancher and homesteader Jim Edwards found that no matter how successful he became, his white neighbors would never look past the fact that he was Black. Edwards and his wife Ethel had moved to the area in the earlier part of the century, seeking opportunity in the region’s booming cattle industry. Thanks to hard work and a bit of luck, they were able to build a noteworthy fortune. A once humble cabin grew into a proper house with a garage, porch, library, multiple bedrooms, and bathrooms with indoor plumbing — a first for many in the area. Still, according to legend, after a drink at a local hotel one evening, Edwards famously vented his frustrations. “Y’all call me ‘Nigger Jim’ now, but someday you’ll call me Mr. James Edwards!”

In a 1989 Annals of Wyoming article about Edwards, Todd R. Guenther wrote that even though Jim was wealthier than his white neighbors, he never felt like one of their equals. Even so, Edwards was arguably the state’s most successful homesteader. And while his story isn’t well-known, he’s long been one of the only examples of a Black person who looked for fortune in Wyoming and found it beyond the realizations of their white peers. It took nearly one hundred years for the next to come along, and few could have guessed it’d be Kanye West.

Like Edwards, Kanye is achieving the American land ownership dream in a state whose name conjures images of everything but Black people. Unlike Edwards, Kanye is an internationally known celebrity with more wealth and pull than most people of any race. Since 2018, when he decamped to Jackson Hole to record a series of albums, Kanye has been flirting with the idea of Wyoming as his site of creative freedom and personal salvation. He’s brought more pop cultural public attention to the state and the broader region than any one person has in years.

And since his relocation to Cody, a town of about 10,000 people, less than half a percent of whom are Black, images of small town white folks rubbing elbows with America’s most controversial Black celebrity have inspired a number of articles about the move. From the New Yorker to the New York Times to the most recent GQ cover story, featuring a photo of Kanye obscuring a Wyoming mountain in a luxury tank. The fascination around Kanye’s presence in Wyoming is more than just pop cultural oddity. It’s centered on the possibility that, in the supposedly all-white and lawless Mountain West, a wealthy visionary, even a Black one, could try his hand at playing God.

Perhaps ironically, Kanye shares more with Cody’s founder Buffalo Bill than he ever could with Edwards. While Edwards knew Wyoming’s land and air with the kind of intimacy only a bootstrapping rancher could have, Kanye and Buffalo Bill are household names that deal in fantasies of the West. Buffalo Bill’s touring Wild West show peddled ahistorical and racist narratives of the Old West around the world. Their success allowed William Cody, the man behind the Buffalo Bill persona, to purchase his own little piece of the land he mythologized, naming it for himself. Similarly, Kanye is hoping to turn his massively successful Yeezy empire into a full fledged city in Wyoming. He describes plans for “Yeezy City” in a recent interview with Bloomberg, saying, “it’s time to go to Level 3.”

Owning a piece of the West has long been a status marker among America’s millionaires and billionaires. The list of stars and magnates that have been scooped up ranches in the region includes David Letterman, Michael Keaton, Tom Brokaw, and Ted Turner. It’s a wave that continues today. Justin Timberlake and Jessica Biel, as well as John Mayer, have all referred to their moves to Montana as a way to escape the superficiality and lack of privacy in Hollywood — not to mention the deadly pandemic currently ravaging the country.

Kanye's vision for the property is a place where he can get in touch with his higher self.

Kanye’s own West Lake Ranch has roots in the gentrification of the range. In the ‘90s, Monster Lake, as it was formerly known, was a sport fisherman site on Mormon-owned land that charged $175 for the privilege of access. In 2006, developers chose the site to be part of a network of luxury resort properties to be known as the Yellowstone Club World. Renamed “Buffalo Bill Ranch” and projected to open in 2008, it was supposed to be an Old West luxury playground for the rich until developer Tim Blixseth, a former timber industry billionaire, reportedly bought the property for $3.8 million and lost it after being sued by YCW shareholders and racking up $400 million in debts the company couldn’t pay. Blixseth soon became a high-profile example of how hard the rich could fall in the gauntlet of the 2008 financial crisis.

Now, in Kanye's hands, the property is once again shaping up to be a luxury playground. While Blixseth wanted to appeal to a generation that grew up on mid-century Old West media, the image from TV shows like Daniel Boone and The Lone Ranger. Kanye’s vision is more in line with a generation that grew up on Rocky Mountain stories like A River Runs Through It and Brokeback Mountain. Narratives where the landscape serves as a backdrop for men “finding themselves.” Kanye's vision for the property is a place where he can get in touch with his higher self, and build a concrete amphitheater and meditation space for all of his followers, too.

In 1993, the Los Angeles Times proclaimed Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming the new safe haven for Black professionals looking for life without the baggage of racial strife. It echoed a popular article about Black people living in Montana that appeared in the New York Times a year earlier, called “Deep in the Heart of Montana, a Black Woman Finds Home.” Both articles discussed the West as a place where white and Black people alike (but notedly not Native Americans) could transcend racial barriers. And the Los Angeles Times, with its opening assertion that “decades of racial isolation [were] ending in the rural West,” implied the promise, specter to some, of the West’s, and thus America’s, thoroughly racially integrated future.

From 1990 to 2010, the Black population of these states did grow, along with each state’s total population, though not enough to justify it as a gathering place for a Black middle class fleeing racism. “My patience has got a lot shorter,” the NYT article’s titular Black woman notably said when Yellowstone Public Radio interviewed for the 15th anniversary of the piece. For his part, Kanye hasn’t spoken publicly on the dynamics of race in his residency in Cody. Most of his public comments on the subject of race suggest he’d rather exist untethered from it altogether. “The most racist thing a person could tell me is that I'm supposed to choose something based on my race,” he said last year.

Instead, Kanye has described his move to Cody with the language of individual liberty. “The building restrictions are way lax in Cody,” he said during an interview before an audience at the 2019 Fast Company Innovation Festival. “That’s one of the reasons why we got to land there, so we can think.” In another interview that month, he connected landownership in Wyoming with freedom, making sure to give credit to President Trump. “We have 12,500 acres in Cody,” he said. “Trump has actually opened up the ability to buy more land and in America — you know America, you can buy land and we can be owners and we don’t often have to be just the product of what black Twitter tells us what we’re supposed to do.”

And some of Kanye's larger aspirations do appear to be coming to fruition. The value of his Yeezy brand partnership with Adidas is reportedly worth around $3 billion. The mayor of Cody, Matt Hall, told Bloomberg that he'd met with the musician to discuss economic revitalization in the region. Kanye West might soon be able to call himself a job creator in the Mountain West.

His ability to absorb Cody, as well as the entire state of Wyoming, into his brand has already proven to be profound. There's the cover of his album Ye, which features an iPhone photo of the Tetons, the corresponding merchandise that eschews Kanye’s name for the word “WYOMING” scrawled above a mountain range, his Sunday Service at Cody’s Buffalo Bill Center that drew hypebeasts of all races into Wyoming from surrounding states, and now a billboard for Yeezy headquarters that sits with a spectacular mountain view in its background.

But Wyoming isn’t as free as Kanye — and deeply-rooted narratives around the state — insists. His plans in Cody depend on how many hoops local leaders and regulators make him jump through, or make disappear. His December run-in with Wyoming Game and Fish proved just as much, when the department delayed construction on his amphitheater. How the majority white town of Cody will respond to the cultural impact of Kanye's presence remains to be seen. But as Jim Edwards’ story tells us, there's nowhere in America where Black people have experienced unbounded, “color-blind” freedom. At least for now, Kanye West is dead set on trying.