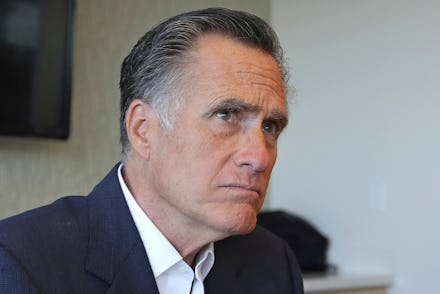

Mitt Romney's secret Twitter account doesn't make him part of the resistance

Over the past several years, Mitt Romney and James Comey have emerged as two of the center-right’s highest-profile standard bearers in the so-called resistance against President Trump, delivering high-minded spiels about the sanctity of norms and civility. They both speak in grand terms: “I do think people will view this as an inflection point in American history,” Romney said in a recent interview with The Atlantic, while Comey, the former FBI director, often tweets profundities like, “This country is so much better than this president.” Crucially, they also share another similarity, though one that’s not especially inspiring: They both appreciate an anonymous tweet opposing the president, given Romney’s confirmation over the weekend that he’s a Twitter “lurker” under the pseudonym “Pierre Delecto.”

It’s obvious that both men would like their opposition to the president to be viewed as a profile in courage. But tweeting under a random name is hardly courageous. Slate’s Ashley Feinberg revealed Romney’s secret Twitter account Sunday, after previously uncovering Comey’s secret “Reinhold Niebuhr” account two years ago. Romney, the former Republican presidential nominee and current Utah senator, first revealed the existence of the account himself, when he told The Atlantic’s McKay Coppins in a profile published Sunday that he uses a secret Twitter profile to follow political news. “I won’t give you the name of it,” Romney said.

But the Utah senator did divulge that he follows 668 people through his account, along with some other key details. Feinberg then used that information to pinpoint the Delecto account. Romney, who did missionary work in France, confirmed Feinberg’s theory by telling The Atlantic, “C’est moi.”

Under the Delecto moniker, Romney often defended himself from criticism that he positions himself as a principled politician but fails to take real principled action. At one point, he replied to the pundit Soledad O’Brien when she decried his “utter lack of a moral compass.” Under the Delecto account, Romney wrote: “Only Republican to hit Trump on Mueller report, only one to hit Trump on character time and again, so Soledad, you think he’s the one without moral compass?” More recently, Delecto replied to a tweet criticizing the Senate’s lack of action on Trump’s decision to abandon the Kurds in Syria, writing, “Agree on Trump’s awful decision, but what could the Senate do to stop it?”

As for Comey, the ousted FBI director never posted from his secret Twitter account, but he did "like" multiple tweets supportive of his various decisions. He recently told The New York Times in a lengthy profile that he sees himself as “not that important” in the “sweep of American history,” but also added that he feels a calling to help make Trump a one-term president. He simply must to keep tweeting — which he now does under a mononymic account, rather than in secret. “I have a fantasy about on Jan. 21, 2021, deleting my Twitter, and moving on to something else,” he told the paper. “But until then, I can’t.” Tweeting is just too important.

Romney and Comey are far from the first politicians to ever adopt a false persona. Trump himself famously adopted the name “John Barron” and called reporters to talk about himself, while his trade czar Peter Navarro was recently revealed to have quoted a made-up analyst named Ron Vara — an anagram of his own name — in several of his books. And who could forget Anthony Weiner, the disgraced Democratic congressman, who called himself Carlos Danger in extramarital sexts?

Leaving aside the hilarious image of Romney, a 72-year-old senator, opening his computer and crankily posting about himself in the third-person, the Delecto account’s existence underscores an essential truth: Being an anonymous Twitter troll does not make you a righteous person, whether you’re an elected representative or former FBI brass. As Delecto, Romney seems far more concerned with his own public perception as a brave resistance knight by future historians than he does in actually doing anything substantial to effect change. After all, as a senator, there are plenty of things he could do immediately to blunt Trump’s agenda, like opposing his judicial appointments. But so far, he mostly hasn’t, voting with the president 80% of the time.

There’s a similar dynamic at play with Comey. Much of his public persona seems to revolve around publicly flagellating himself and expressing regret over his role in the Hilary Clinton email saga, which data whiz Nate Silver has posited tipped the election to Trump. Trouble is, he’s doing this via platforms like paid speeches, many of which, he told the Times, pay well into the six figures. “It’s a lot of money!” he enthused. In that context, his pensive public veneer begins to look a bit facile.

Both Romney and Comey have tried to frame themselves as renegade Republicans unafraid of speaking truth to power. But as far as outspoken bravery goes, anonymous Twitter escapades rank pretty low on the list.