Montana is ground zero for Native American voter suppression — and the fight against it

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 banned discriminatory voting practices and gave Native American communities the right to vote — in theory. Most of us know, though, that even with the Voting Rights Act in place, voter suppression is still going strong. In Montana, Native Americans are fighting new Republican laws that further restrict their ability to vote.

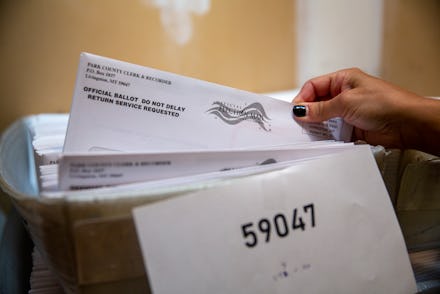

This year, Montana Democratic Gov. Steve Bullock, who served for eight years, was replaced by Republican Greg Gianforte. With a Democrat no longer holding veto power, state Republicans took advantage of Gianforte's election by passing two new voting law bills: House Bill 176, which eliminates same-day voter registration, and House Bill 530, which makes it illegal for people to distribute or collect mail-in ballots if they're being paid to do so.

Montana Republicans defend the laws as necessary for voter security. In April, Montana state Rep. Wendy McKamey (R), said in defense of H.B.530, "There are going to be habits that are going to have to change because we need to keep our security at the utmost." She went on to add that H.B.530 would keep elections as "uninfluenced by monies as possible."

However, McKamey's defense completely ignores the reality of voting within Native American communities. Per the National Congress of American Indians, the turnout rate amongst Native voters is up to 10 percentage points lower than any other racial group. In 2019, the Brennan Center reported that restrictive voting laws throughout the country continue to disproportionately impact Native communities.

On the surface, preventing people from being paid to collect ballots might seem like an okay idea. But in Montana, local nonprofits like Western Native Voice and Montana Native Voice pay people to collect and distribute ballots as an important part of their voting strategy. Without this practice, many people would be unable to cast their ballots at all. For example, The New York Times reported the story of Laura Roudine, a resident of the Blackfeet Indian Reservation who had emergency open-heart surgery only a week before the 2020 election.

Because of the risks that coronavirus posed, neither Roudine nor her husband could vote in person. Home delivery wasn't an option, either, because it doesn't exist in her area of the reservation. Instead, the Times reported, the couple relied on Renee LaPlant, a Blackfeet community organizer with Western Native Voice, who took applications and ballots back-and-forth between their home and one of the only two satellite election offices located on the 2,300 square-mile reservation. The new laws signed by Gianforte would make this practice illegal.

Unfortunately, the situation unfolding in Montana isn't unique. For decades, Republicans have attempted to enforce stricter voting laws in the name of security. But in practice those laws typically just make it harder and harder for oppressed communities to vote. Ahead of the 2020 elections, Republicans focused their voter suppression efforts on poll-watching, raging against mail-in voting, gerrymandering, and opposing legislation that would allow people with felonies to vote.

For Native American communities, voter suppression often takes shape through laws like the ones in Montana or voter ID laws. In 2017, the Native American Rights Fund and two North Dakota tribes sued North Dakota over a law that required a physical address to vote. About 22% of Native Americans and Alaska Natives live on reservations or other trust lands that don't use street addresses. The lawsuit stated that the requirement "denies qualified voters equal protection under the law in violation of the North Dakota Constitution."

Geography alone also plays a role in suppressing Native votes. Most reservations are rural and, as a result, lack the infrastructure that you may find in cities or even predominately white rural areas. The Times reported that while the Blackfeet reservation in Montana is about the size of Delaware, it only had four ballot drop-off locations last year; one of those locations was listed as being open for only 14 hours over two days. Other reservations simply don't have polling places at all. To vote, people need to go to the county seat, which is only possible if you have a car and the ability to take time off for a lengthy drive.

Native American communities in Montana are organizing against these voter suppression efforts. In May, the ACLU of Montana and the Native American Rights Fund sued on behalf of several Native voting rights organizations and four Montana tribal communities, stating that the new laws will disenfranchise Native voters in the state. The Montana Free Press reported that Alex Rate, the legal director for the ACLU of Montana, specifically pointed out that H.B.530 is eerily similar to the Ballot Interference Prevention Act.

Like H.B.530, the Ballot Interference Prevention Act tried to restrict who can collect ballots, and set a six-ballot limit on collections. Last year, though, District Court Judge Jessica Fehr out of Billings, Montana, struck down the legislation, writing in her order, "The Court finds that BIPA serves no legitimate purpose; it fails to enhance the security of absentee voting; it does not make absentee voting easier or more efficient; it does not reduce the costs of conducting elections; and it does not increase voter turnout."

Fehr went on to add that testimony from the plaintiffs showed "that BIPA will significantly suppress voter turnout by disproportionately harming rural communities, especially individual Native Americans in rural tribal communities across the seven Indian reservations located in Montana by limiting their access to the vote by mail process."

"Native people have been fighting for the right to vote and fair and equal access to the polls for the last 75 years," Ronnie Jo Horse, executive director of Western Native Voice, said in a statement regarding the recent lawsuit. "We are now in 2021, and instead of dismantling barriers to the polls for citizens we serve, some Montana legislators have quickly built them back up even though a Montana court previously ruled the obstacles created for Indigenous voters 'are simply too high and too burdensome to remain the law.'"