The best dystopian books to read while in self-quarantine

Four weeks ago, while sitting in my office (remember those?), I pitched an idea for a book review: it was about how we didn’t need more dystopian fiction. How the new dystopian fiction was just a hyperreal version of non-fiction. When I had that idea, I had no idea what was to come.

Today, we’re in the midst of a widespread quarantine due to a highly infectious respiratory disease that has stomped, like a petulant toddler, gracelessly across the globe, leaving its footprint in every city, country and continent. We’re attending virtual happy hours and opening doors with our toes. Like the characters in beloved disaster-novels like Mary Shelley’s The Last Man and Stephen King’s The Stand, we are watching the world as it is flipped inside out — racing to keep up with the spread of a deadly disease. Which is to say: If you’re in the middle of writing a piece of dystopian fiction, put the pen down and take a close look around you. Material abounds.

The dystopic genre, these days, feels more like a blend of memoir and auto-fiction, books written from the rich materials of day-to-day reality. From a startling look at the American carcinogenosphere, to a bleak depiction of the Silicon Valley hellscape, to a hyper-real portrait of a late-capitalist corporate office, the most compelling books about contemporary life remind us that dystopia is now.

Seeing as the current condition finds us all indoors for the foreseeable future, here’s a list of books you won’t find in the “dystopia” section of Amazon (our other all-powerful overlord), as told by authors who have long known that we’re already living it.

Ben Lerner - The Topeka School

In Ben Lerner’s auto-fictive The Topeka School, the year is 1997 and a previously asymptomatic disease (that’s been manifesting for generations) has taken a targeted hold of a large swath of American white males. And its effects are toxic. So toxic, in fact, that years later, sociologists will later refer to the infection as exactly that: toxic (and then the demographic it targets) masculinity. When describing the disease and its grasp on the protagonist, a character based off of the author himself, Lerner uses language associated with satanic possession, more so than adolescence: “Adam often feels lost and enraged for reasons he can’t quite explain. His behavior at home grows so explosive that his parents insist he either see a therapist or learn biofeedback methods for regulating his emotions.” The result of this “disease,” which is spread via language (and its distortion), can be harmful, offensive and in some cases, deadly: “among his peers, the most expressible emotions are rage or disdain, and the lingua franca is physical violence or torrents of freestyle rap in an absurd--if earnest--appropriation of a black culture they have no direct contact with,” Lerner writes.

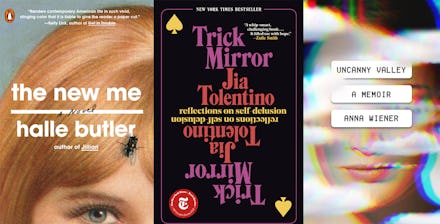

Anna Wiener - Uncanny Valley

Anna Wiener’s memoir, Uncanny Valley opens like a dystopian novel. A city is on the brink of radical change — the technocrats have risen, pushing entire generations out of their homes, their jobs, and their lives with their VC funded start-ups and their blurred buses that haunt the city like ghosts. Surveillance is their weapon of choice, and it’s wielded by myopic and self-aggrandized men who, like Lerner’s characters but two decades in the future, build their own language and surrounding ecosystems for their own profit.

Unlike Lerner’s characters, however, the men that make up Silicon Valley run on a strict diet of data, cold brew and a dangerous level of male confidence. As the only female on her “non-technical” team, Wiener writes that her job “ had placed [her], a self-identified feminist, in a position of ceaseless, professionalized deference to the male ego.” In summation: the villains in Uncanny Valley are like Big Brother if Big Brother wore performance fleece, ran a 5k every weekend and worked, just like anyone else, in the center of some not-so-special open-office plan.

Jia Tolentino - Trick Mirror

In Jia Tolentino’s essay “The I in Internet”, from her compendium of non-fiction essays titled Trick Mirror, the internet is a drug pumped involuntarily into the veins of an unsuspecting populace — leaving its subjects dulled, numb and strung out: “Like many among us, I have become acutely conscious of the way my brain degrades when I strap it in to receive the full barrage of the internet,” Tolentina writes, “these unlimited channels, all constantly reloading with new information: births, deaths, boasts, bombings...confessions and political disasters blitzing our frayed neurons in huge waves of information that pummel us and then are instantly replaced.” Tolentino, our heroine throughout, relies on the internet as a freelance writer.

As a result, she’s both hyper-aware of its acute power and entirely powerless to it at the same time: “I’ll sit there like a rat pressing the lever, like a woman repeatedly hitting myself of the forehead with a hammer, masturbating through the nightmare until I finally catch the gasoline whiff of a good meme.” Its most dangerous outcome, however, is its ability to desensitize and homogenize, “to extract individuality from entire generations, leaving them like cusks of themselves, overexposed and calcified by the onslaught of information.” Arguably worse than any deadly pandemic (I’m short of breath, again, just writing that) or alien invasion, both of which either kill or possess their population, the internet leaves us in a strange in-between--like neutered and unfamiliar versions of ourselves left to play-act through a virtual life built for us by the almighty, Patagonia-wearing overlords.

Halle Butler - The New Me

Hell, in Halle Butler’s auto-fictive The New Me, takes place in the back offices of a mid-western furniture depot. Alienated, alone and apathetic to a nearly pathological degree, Butler’s main character, Millie, is the deflated and bereft product of her environment: a late-capitalist purgatory where no job is secure (Millie is a temp, which, she’s at least grateful for in terms of its variety: “like how people switch out their cats’ wet food from Chicken and Liver to Sea Bass, but in the end, it’s all just flavored anus”); where depression is an inevitable part of the quotidien (because, “how could she afford therapy on twelve dollars an hour?”) to be treated only with “alcohol, back-to-back episodes of true-crime TV, deadpan humor and delicious hostility.” More so than any other modern dystopia, the drone of Millie’s darkness was perhaps the hardest to bear. Butler’s sharp wit gives her vitriol a certain seductive syncopation that turned the act of reading into something closer to indulging in a bad habit. Before you know it, you’re complicit in her actions (or in-actions), parroting a person you never wanted to be. When describing Millie’s job, Butler says: “there’s pleasure in her work, but it’s the sick, obsessive pleasure of looking under a bandage at a wound.” Which, though harsh, sums up the phenomenon of reading her prose perfectly.

Anne Boyer - The Undying

The last (and least navel-gazey) on the list is Anne Boyer’s memoir, The Undying, where dystopia is at its most acute as it pertains to illness, the abandonment of care and the “ruinous carcinogenosphere” in our country. Boyer, who was diagnosed with triple-negative breast cancer at 41, the type of cancer that leaves you with less than 50 percent chance of survival, finds herself waging a war against three opposing forces: the first being the actual disease that’s killing her, the second is the course of toxic drugs administered to save her (one of which is literally a “medicalized form of mustard gas”), and the third is the automation with which her treatment is administered (the result of, (you guessed it!), capitalist and technological advancement) and the alienation it causes. It is the conflict of tech as a means for progress but also dehumanizing neglect that is the most familiarly unsettling part of Boyer’s experience, and the novel at large: “Illness that never bothered to announce itself to the senses radiates in screen life, as light is sound and is information encrypted, unencrypted, circulated, analyzed, rated, studied and sold,” says Boyer. After a double mastectomy that’s been deemed an outpatient procedure, Boyer is forced out of the hospital before she can even walk. Which proves that in Boyer’s world, which, most unsettling is a world we all share, there is nothing human about saving a life.