The Democrats' strategy is clear: appeal broadly, but not deeply

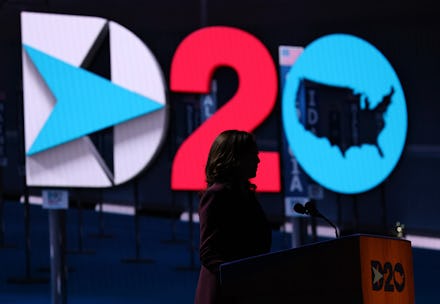

Hard as it may be to believe in these timeless pandemic months, but we're in the thick of convention season, that quadrennial stretch of political pageantry whose true purpose — officially nominating the men and women each major party has chosen to run for president — is often overshadowed by bizarre stunts and hack-y armchair punditry.

Still, given how much President Trump's time in the White House has instilled in our daily lives a pervasive feeling of cataclysmic extra-ness, this year's Democratic and Republican conventions carry an additional sense of significance and import — one into which the Democrats have leaned heavily, resulting in a convention that feels a mile wide but an inch deep.

If there has been an overarching theme to this year's DNC, it's broadly that Donald Trump is bad, and everyone — Democrats, Republicans, independents, and hey there, Republicans again! — should vote him out. Yes, there have been moments lauding soon-to-be-official nominee Joe Biden, but for the most part, those moments existed primarily to augment the overwhelming drumbeat of "Trump bad." To the extent that there are any specifics about what Biden actually stands for, they're largely presented in the service of the broader, nebulous "Joe good, unlike that other guy!!" framing of entire convention.

Consider the pomp and celebration the Democrats had while rolling out their list of high-profile Republican speakers: Colin Powell, Cindy McCain, and former Ohio Gov. John Kasich, standing at a literal crossroads for some unfathomable reason. All three tourists from the other side of the aisle had lovely things to say about Biden, of course, but their specific remarks are almost an afterthought to the fact that they're at the DNC in the first place. In a week, no one is going to be quoting Kasich's speech, or lauding McCain's oratory skills. If the Republican participants are remembered at all, it will be for simply showing up in the first place.

In a sense, "showing up" is the perhaps the main takeaway from the DNC so far, from its insanely wide net of participants down to Michelle Obama's already-iconic "vote" necklace. "Vote," the Democrats are shouting. "Vote for Biden, because even a few Republicans think Trump is bad." Well, sure, but that's hardly a compelling affirmation for why Biden is good. Leaning heavily on the simplistic platitude of "vote" is a an easy way to try and bring as many people into as big a tent as possible, without having to bother them with the nitty-gritty details of "for what?" or "why?"

While Democrats have framed their convention as a "we're all in this together" exercise, the Trump campaign has demanded total allegiance rather than coexistence.

The ultimate effect is that the DNC feels a little lackluster and aimless. This is, of course, partially due to the awkward constraints the coronavirus pandemic has placed on the entire enterprise. Robbed of a cheering arena and the palpable energy an actual, in-the-flesh audience brings, the DNC is left without a crucial tool for exciting its base — arguably the most important thing a convention can do for a campaign. Instead, the convention feels like the product of a party stretching itself too thin to appeal to as many people as possible in an empty room, without bothering to anchor itself in something more concrete than opposition.

Perhaps that will change when Biden gives his keynote speech on Thursday night. Perhaps he will finally be able to reframe the race between him and Trump as more than just the current "don't vote for him" vibe — a strategy that, while decidedly uninspiring and untenable in the long run, has so far served its purpose. Perhaps he'll deliver a concrete and compelling "here's what I can do for you" pitch, which his running mate Kamala Harris started for him in her closing address Wednesday night.

The Republicans, on the other hand, have already signaled that theirs will be a wholly different type of convention — one focused on anger and victimhood, with speakers like the St. Louis couple famous for brandishing guns at protesters walking in front of their luxury home, and Nicholas Sandmann, the teen filmed smirking at an Indigenous elder on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, who later settled defamation cases against CNN and The Washington Post. Even the president's plan to accept his party's nomination from the White House itself is part of a larger framing of the RNC to prop Trump up as a singular strongman who represents the aforementioned aggrieved Americans.

Unlike the Democrats, who have spent their convention thus far trying to appeal to everyone, the RNC is shaping up to be laser-focused on the president's base, and their hyper-specific animating bugbears. If the Democrats are at risk of stretching themselves too thin, the RNC (and the Republican Party itself) is taking the opposite route, contracting in upon itself until it is a dense, impenetrable core whose strength is its immovability rather than its range. While Democrats have framed their convention as a "we're all in this together" exercise, the Trump campaign has demanded total allegiance rather than coexistence — and presumably will continue to do so well past the RNC.

Ultimately, both tactics may not do much for their respective candidates. If Biden can't convince people the race is about voting for him, rather than against Trump, then he's putting the power in the hands of the president and hoping Trump simply continues to drive away more and more prospective voters. It might be a decent bet, but it's hardly the stuff of a compelling campaign — not to mention it looks mighty familiar. The president, meanwhile, is counting on keeping his base agitated and in perfect, angry lockstep. His campaign isn't about appealing beyond what we've seen from him before; it's about shoring up what already exists, and hoping that's enough.

Either way, we're nearing the halfway point of convention season. After that, it's just a few scant months till Election Day, when we'll know one way or another whose convention gamble actually paid off.