Trump's border wall cuts through sacred land. One tribal leader is determined to stop him

When President Trump announced plans to build a wall along the Rio Grande River, Juan Mancias smelled a rat. Mancias is the Carrizo/Comecrudo tribal leader and a founding member of the Texas chapter of the American Indian Movement — not to mention an experienced human rights advocate and Native rights activist. When Trump first touted his plans to run a border wall through South Texas back in October 2018, Mancias couldn’t make sense of how this new construction would help protect the border, where his family has lived for generations. Through some document digging, though, he’d eventually uncover a possible alternative reason the government was so desperately seeking a border fence in this area — and Mancias thinks it has little to do with national security.

The land in question snakes through Cameron, Starr, and Hidalgo counties, passing through the city of Brownsville and up to McAllen. Included in this region are multiple Carrizo/Comecrudo tribe burial sites stretching from the Garcia Pasture down to the Eli Jackson Cemetery. The Carrizo/Comecrudo people were in Texas long before the Spanish colonists or any other white folks set foot on their land; the entire Rio Grande Valley is their ancestral home.

Mancias is an intense man — tall, with long silver hair and a commanding presence. Years of legal battles over land and human rights atrocities have left Mancias suspicious of simple answers and fluffy rhetoric. Case in point: When the city of San Antonio asked him to come to the Alamo as a “spiritual leader” for an anniversary speech in the spring of 2018, Mancias didn’t offer warm words about cultures bonding. Instead, the tribal head flipped the script, speaking at length about the slaughter of Native people on the supposed “hallowed ground.”

Given his generations-long commitment to the land and his status as a revered community leader, Mancias is uniquely qualified to lead the charge against this section of Trump’s border wall. His initial question was simple: Why is the Trump administration pushing so hard for a glorified fence in the Rio Grande Valley, where the river itself has long served as a natural wall since boundary lines between Mexico and the U.S. were established in the 19th century?

With a width of nearly three football fields, pollution from years of misuse, and powerful undercurrents, the Rio Grande River is already a deadly barrier to entry for immigrants and refugees attempting to slip across the U.S.-Mexico border unnoticed. And if the topography weren’t enough on its own, there’s also comprehensive U.S. surveillance in the area. Government helicopters patrol the skies, while state and local law enforcement cruise adjacent roadways and patrol the water with speedboats, keeping an eye on the river 24/7.

In other words: There are plenty of longstanding obstacles to illegal border crossings. That’s why Mancias started digging for another reason to build a border wall — and he found that 28 Environmental Protection Agency laws, including the National Environmental Policy Act, Clean Air Act, and Endangered Species Act were being ignored in order to force the wall through. The structure would disrupt historic tribal lands and create a path of destruction through the Rio Grande Valley National Wildlife Refuge and down to the National Butterfly Center, a federally recognized preservation area for a variety of wildlife species and a critical stopping point for migrating monarch butterflies.

Mancias’s theory is this: The government is using the border wall to hide what they really want to build, which is a liquefied natural gas pipeline. Both projects would infringe on tribal lands, but per Mancias, the border wall is the patriotic cover story that allows the government to secure the permits and land deeds they need to plow the pipeline project forward. The Carrizo/Comecrudo tribe sees themselves as protectors and defenders of this land. From the rocks to the trees, this place is their history, even if they are a relatively small group at only 2,500 members. So they plan to fight the incursions.

After decades working to advance Native American causes, Mancias has established a two-fold method of attack for when problems like this arise. The most visible side is the public fight and begins when a group of protesters occupy the indigenous site under threat to ensure safety and preservation. But historical nightmares like Wounded Knee and recent occupations like Standing Rock have made clear to Mancias that this isn’t enough to win the public battle. It’s the work done behind the scenes — researching and preparing for contentious court battles — that is the only way to truly beat the federal government.

Mancias reached out to Ray Cavazos, a native of the Rio Grande Valley whose family’s presence in the area dates back to pre-Spanish rule. The Cavazos family owns a large piece of property along the river. For generations, this slice of the Rio Grande has been quiet, but now, it’s littered with noise pollution. Only a patch of tall grass and bamboo separates Cavazos’s property and Trump’s wall — hardly enough to keep out construction noises.

Tell me where the immigration crisis is. Because I don't see it ... This is pure hate.

The thing people don’t understand about the wall is that it’s not one long stretch of fence. It’s pieces of steel situated on various parts of available property. Cavazos and his family immediately granted the Carrizo/Comecrudo tribe permission to camp on their land, should they want to act as watchdogs while the government’s bulldozers inch closer every day.

"This wall is the dumbest of the dumb,” Cavazos told Mic in December while watching the purple sunset over the water from the dock he and his cousins built by hand as young boys.

“Anyone who knows this river knows the wall is going to kill this land,” Cavazos says, “and soon these banks are going to be gone. The river already carries natural debris. The wall is going to lead to further erosion which will clog up how [the river] moves. It'll create a dam. Who's going to pay for that?"

Cavazos stood quiet for a moment, with the stillness of the water behind him, before spreading his arms out to indicate the silent landscape. "Tell me where the immigration crisis is,” he says. “Because I don't see it. I don't know what these people are thinking. This is pure hate."

Because Cavazos’s family hasn’t granted the government permission to build on their land, the wall will be constructed instead in bits and pieces all along the border. Not only is that worse for the surrounding environment, but one could also argue that it seems like more work than it’s worth. Just about everyone along the border knows that if they deny the government, they’ll eventually end up in court.

In this case, that’s the outcome the tribe is hoping for, given that they don’t have the same legal claim to the land on paper that a deeded landowner would. Recently, a judge has allowed a lawsuit to move forward in the courts with both landowners and the tribe represented, and a new court case is coming in November.

Mancias agrees with Cavazos that the wall would devastate the Valley, but he knows an argument about disrupted butterfly flight patterns or overarching racism won’t win this fight. If he can raise awareness of how the proposed sites would desecrate Native burial grounds, though, the tribe might stand a chance.

The tribe has representation in Washington with the Bureau of Indian Affairs, but because they’re not a federally recognized group, the government has no obligation to adhere to any Native American protection laws when it comes to disrupting Carrizo/Comecrudo lands — like Garcia Pasture, located down near Brownsville.

Garcia Pasture was a massive hub of commerce for Native tribes, and as a result, the site is rich with artifacts. But a proposal for a liquefied natural gas pipeline that originated in 2016 has recently started to take shape — and its proposed trajectory would disrupt Garcia Pasture. Called the “Rio Grande LNG,” the pipeline is a massive undertaking, with a 984-acre pumping station sitting smack-dab in Brownsville.

The LNG pipeline is what Mancias found when he started digging through files, following his hunch that the border wall near McAllen made no practical sense. Since discovering the pipeline plans in 2017, Mancias, along with other ecological rights groups, has protested any further disruption of the Garcia Pasture area until its full cultural potential is known. As of today, over 300 Native American artifacts, in addition to ceremonial graves, have been found there.

Mancias sees the pipeline project as another example of companies trying to bulldoze the environment to push their capitalist agenda, just as Trump has already done to clear the way for his wall. So since 2017, he has been working around the clock, filing injunctions, using writs of seizure and sale, looking for every loophole — every piece of legislation on the books — to tie the wall up in courts.

Meanwhile, in neighboring Hidalgo County, another sector of the tribe’s most cherished land — the Eli Jackson Cemetery, which is home to many of their ancestors — is in danger of being disturbed by Trump’s construction plans. Up until about a year ago, most people in the Valley didn’t know what the Eli Jackson Cemetery was or where they could find it. Located off a dirt road about 15 miles outside McAllen, it's not the kind of spot people go looking for. But buried at the Eli Jackson Cemetery are Carrizo/Comecrudo veterans from World War I, World War II, and the Korean War, along with others in graves that pre-date Texas.

The tribe heard about the possible disruption of the Eli Jackson Cemetery and Garcia Pasture back in 2005, although nothing really started to take shape until late 2015 when an inside government source let them know what was being planned for the pipeline project. That’s when the tribe and other concerned parties spurred into action.

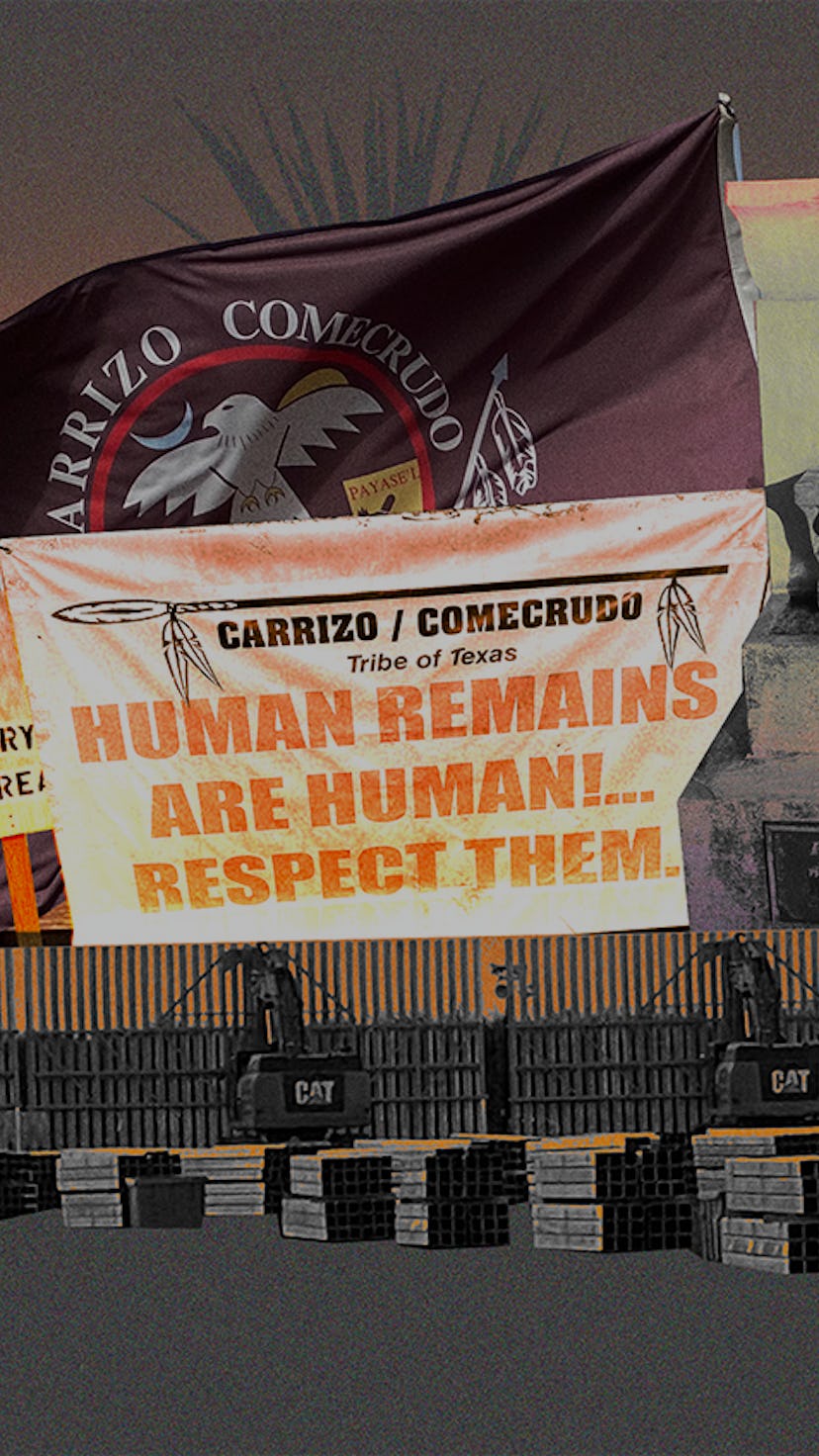

After learning of the threat to this land, the Carrizo/Comecrudo tribe moved quickly to protect the sacred area, setting up what they dubbed the “Yalui Village” camp at the entrance to the graveyard. It’s dotted with tents and shelters, along with a fire that sits front and center in the graveyard that they believe can’t be put out; for the tribe members, the blaze is a symbol of cleansing and renewal, an emblem of their fight. The goal is to stop anyone from trespassing on this sacred land — especially the government. The small settlement has flags championing indigenous rights, along with a giant yellow banner that bellows: "Human Remains Are Human! Respect Them."

At the camp, Mancias and his tribe have welcomed outsiders who have joined in the fight against Trump’s border wall. Former freight hoppers who go by the names of Wolf and Danny jumped trains down to South Texas to join the resistance. "This is important,” Wolf told Mic in December, while stoking the fire at Yalui Village. “We can't let them build a wall based on greed."

So far, Wolf and Danny have equipped the graveyard camp with solar panels and a mobile kitchen. They also keep an ever-present eye on their surroundings. Awareness is especially important when Mancias is on-site, because government officials seem to magically appear in his wake, he says.

“Whenever I’m at Yalui,” Mancias says, “you’ll see choppers over the property more than usual. You’ll see undercover trucks. They’re always watching. They don’t like it when I come around.”

We want to make sure they recognize our presence.

"We left for two days,” he adds, “and the truck we keep on the property was messed with. They did a whole bunch of stuff to the engine. They pulled spark plugs so it couldn't run."

Government officials have denied to Mancias that they meddled with his or his tribe’s property. And last July, U.S. Customs and Border Patrol said it would “avoid” the Eli Jackson Cemetery land while still fulfilling the mission of Trump’s border wall. (Mic reached out to various federal and state agencies for comment on this story, including the Department of Homeland Security, the Bureau of Indian Affairs, and the Texas governor’s office, but none replied.)

Once the Yalui Village camp was up and running and the court battle pending, “we filed a cease and desist to stop the wall going forward,” Mancias says. “We want to make sure they recognize our presence.”

All the while, Mancias dug deeper into the Trump administration’s plans. He had a hunch from the tribe’s efforts near Brownsville that the connection between the LNG pipeline and the border wall wasn’t coincidental. “When they said the LNG pipeline was happening, we went down [to Brownsville]. We got involved in the fight against fracking, we assisted landowners, fighting against building more wells. We set up camps, we’ve been fighting the toxic waste issue.”

“Now, they’re using the wall as a cover up,” he says. “This is about oil, not safety.”

The pipeline is being developed with as much help from the state of Texas as possible, but while you can Google its name and look at the plans, no one is really talking about it. News of a South Texas pipeline isn’t a secret, but it does make for a convenient distraction for the government, per Mancias's theory.

Mancias knows answers often lurk in seemingly benign government documents, so he checked permits and land use codes and discovered a vital piece of information. Turns out, "this wall isn't actually on the border,” Mancias explains.

The Los Angeles Times quoted a Border Patrol official in 2018 who acknowledge that the topography in south Texas made for some unique hurdles. “The Rio Grande has a set of challenges nowhere else has in that the wall is not on the border, and there’s some homes we have to accommodate access to,” the official said. Per Mancias, that's exactly the issue.

“They're creating a no-go zone that will disrupt lives thanks to eminent domain. We'll be blocked from the water and the land this community has known for generations,” he says, noting records available in Zapata and Webb Counties in particular, which stretch east up the Texas border from Hidalgo County (home to McAllen). In Zapata and Webb Counties, the government has applied for permits to build pipelines. “Anyone can go right now to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission,” Mancias says. “It’s public knowledge.”

The guise of new jobs and industry coupled with good ole’ American scare tactics could help get the wall up while also laying the groundwork for the Rio Grande LNG. It’s the perfect storm of private business and public funding, if you ask Mancias. His theory isn't confirmed, nor is it an overarching narrative, but it is one that the longtime tribal leader believes. And because the building of the wall will facilitate the clearing of the tribal land, Mancias says, when citizens do eventually get wind of the shady practices, it will be too late. The land will be already taken.

“They say it’ll be clean, but it won’t,” Mancias says of the LNG pipeline. “We believe they’re staging attacks, ramping up the border scares, to get this pushed through.”

Could South Texas become another Standing Rock? Is the wall about protecting Americans, or is it a red herring to facilitate pipeline greed? If you ask Mancias, he'll tell you it's just business as usual.