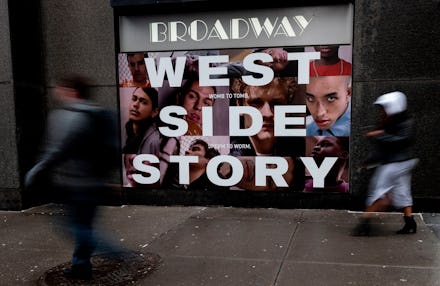

The modern adaptation of 'West Side Story' tackles our uneasy relationship with surveillance

In Belgian theatre director and provocateur Ivo van Hove’s exhilarating revival of West Side Story — originally produced on Broadway in 1957 and conceived by choreographer Jerome Robbins — surveillance is embedded in the lives of its characters. A contemporary imagining of the musical — which is based on a book by Arthur Laurents that is itself loosely based on Romeo and Juliet, and that features music by Bernstein, with lyrics by Stephen Sondheim — it’s as if the rival gangs and the two star crossed lovers caught in the middle, Tony and Maria, have never known any other reality other than that of watching, being watched, and watching being watched. Van Hove, choreographer Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker, set designer Jan Versweyveld, and videographer Luke Halls assert that cameras and screens have consciously and unconsciously shaped how these characters navigate the spaces around them.

The original production of West Side Story, and its film adaptation in 1961 which was directed by Robbins and Robert Wise (The Sound of Music), imagined dancing — high balletic kicks and cutting, sensual swipes — as the primary language with which to distinguish the Polish Catholic Jets and Puerto Rican Sharks; those contrasting vocabularies could fill out the broader concrete landscape around them, as their respective dance lexicons clashed, as deadly as any switchblade. It was a dance musical, with symphonic ballet pieces to expound on its ideas of Utopia in times of conflict; van Hove’s new production sheds the Robbins choreography, cuts a song, tightens the production to 105 minutes, gives more overlapping language between the gangs, and adds video to its vocabulary of distilling the world in which these people live in and their relationship to a broader society.

As Leonard Bernstein’s cityscaping saxophones, oboes, and clarinets paint a sonic portrait of the sharp, jutting lines of New York, a cluster of mostly men walk across the stage, glaring into the audience. Their skin wrapped in tattoos and piercings, exposed to indicate that physical vulnerability is their strength, their eyes convey both toughness and a world weary irritation. Blue light shines down on them — the Jets, mixed with members black and white — on the bare stage. Behind them, a gigantic wall that turns into a display. A camera somewhere in front pans across their faces, texturing the degree to which their social circumstances have been etched into their skin. The lights turn red and the Sharks — Latinx with varying skin tones — assert their place on the stage, just as inclined to stare into the audience’s eyes. We’re watching them, and they’re watching us watching them.

Van Hove has used video, projection, and live feeds throughout much of his career both at his home theatre Toneelgroep Amsterdam and on Broadway in work like The Crucible and Network. The impression is that videos and screens have irrevocably changed the way we foster intimacy. And how we obfuscate. In many of his shows, he’s dealing with adults and their relationship to screens and personae; if van Hove’s use of video risks becoming a crutch, West Side Story provides him the opportunity to engage with people for whom these screened realities are simply native to our/their perception of the world.

As the Jets and Sharks tumble on stage, a cameraman, also dressed in tattered clothes like he’s a member, snakes his way through the fights, capturing the chaos. When they’re dancing as if in a competition at the high school, shots from overhead superimposed onto one another, their bodies bleeding into one another. They’re flattened as spectacle, but aware of it, playing into an audience thirst for the theatricality of division as show. For outsiders of these communities, and in turn Broadway audiences, the violence between the marginalized is a spectacle in itself.

But Doc’s, the little shop Tony works at, having left the Jets, occupies a deep hole in the same screen where images are projected, like another space separate from a battlefield; and the footage, once clear and in color, turns greyscale with a tinge of green, sharply angled like it’s in the corner of a ceiling. We see what looks like a bodega security camera’s grainy low resolution footage.. The Jets pay little attention to the camera, as if it’s been there for so long it’s faded into the background.The bridal store where Maria and Anita work is filled with cameras too. In corners, the field of vision wide enough to capture what’s on their little TV as they sew. There’s a camera in Maria’s room, in the stairwell. There’s a camera even where there isn’t a discernible “set”.

Over the course of the musical the gigantic screen projects languid tracking shots of East Harlem and the Bronx, sometimes with the characters running through them like a jungle gym, sometimes totally deserted. The streets are mostly clean.Smooth, blue and black with amber street lamps, detailless. It is New York and it could only be New York; or could it? Van Hove and videographer Halls establish a texture of New York in West Side Story, but that New York’s identity has radically obliterated into anonymity due to gentrification. This, too, is contrasted by a collage of apartments and interiors during “America,” as the Shark men and women debate the advantages and dangers to assimilating into American society and whiteness (Girls: “Life is all right in America”, boys: “If you’re all white in America”); images of close knit communities and the conditions they must endure are contrasted with scenes of Puerto Rico, the dialogue coming to similar conclusions regarding inequity. “Tonight (Quintet)” turns these actualities and experiences into a cyclone of images and sound, layering one on top of the other, so that the real world and the filmed on are barely delineated, not unlike the performance of machismo melding with its ugly truth.

Camera phones, too, are in West Side Story, documenting pride, protection, and humiliation. Riff, the leader of the Jets, and Bernardo, the leader of the Sharks, plan their rumble with members of each documenting the escalating tension both like a memento and an argument in favor of their strength. And a camera phone, too, is used to record an assault, a pivotal emotional and plot point in the musical. But most startlingly, the reality of surveillance feels most palpable whenever Schrank, the local police lieutenant, and Krupke, a cop, are present. A threat from Krupke is deescalated when a Jet pulls out his camera and begins filming, another sharp reminder of van Hove’s reconciling with the original text and how the sociopolitical landscape has changed in the wake of its original conception. The once jovial and comic song “Gee, Officer Krupke” jesting about the ways in which these characters, who are predominantly black and brown, are marginalized by institutions like the police and the prison industrial complex (yeah, it is usually played for slapstick) transforms into a mirthless rejoinder to those very threats. Shots of police officers arresting young men, young men in interrogation and counseling rooms, young people being handcuffed and put into the back of cars, and young men with their hands up play behind the Jets as they find the harshness of the black comedy and ask for a blood curdled laugh. As they sing, “Gee, Officer Krupke, We're down on our knees, 'Cause no one wants a fellow with a social disease”, they get down on their knees with their hands behind their heads, provocatively recalling “hands up, don’t shoot”. There are cameras and screens everywhere. Basically, someone is still watching even when “no one” is there. If no one’s there, the state is.

Though changes and additions to the show, including its use of video, seem button pushing and dramatic revisions, these adjustments remain immensely faithful to the essence of West Side Story and its ideas. Van Hove and his team have allowed the details of the text to evolve, live, and breathe.

There are crucial moments where van Hove lets his Tony and Maria break from Brechtian artificality, they find freedom and liberation in the wide open space of the stage as they sing “Tonight” and break away from the bridal shop cameras during “One Hand, One Heart.” Though we can see their proximity from one another in more detail on these big screens, their eroticism explodes when it’s just them on the stage. Tony and Maria’s closeness reaches a climax in “Somewhere”; no cameras or background, just the two on the floor, electric and tactile. When they sing, “there’s a place for us”, it’s hard not to imagine that the Utopia imagined in this West Side Story is one beyond the gaze of clashing communities, racist institutions, and a bigoted society. A place for Tony and Maria can see and be seen on their own terms. For a moment, you’ll believe their doomed romance can survive; with no screens or video in sight, the music floats in the air, “Somehow, someday, somewhere!” Were that place real, we shouldn’t be watching, just finding a new way of living.