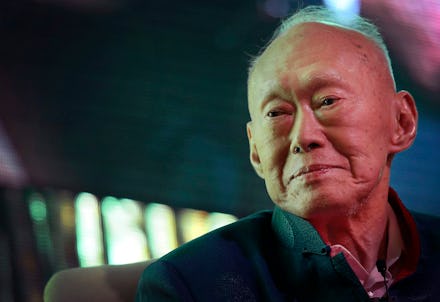

What the U.S. Can (and Can't) Learn from Singapore's Founding Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew

Singapore's founding prime minister, Lee Kuan Yew, died Sunday at the age of 91. Lee, who is widely credited with transforming the country from a third-world backwater into a first-world powerhouse, had been in poor health for several years.

Lee led the country from 1959 until 2000, a period which saw Singapore achieve independence from both England and Malaysia. He remained active in Singaporean politics long after his official retirement, and served as an adviser and consultant to governments and leaders around the world.

"He was a huge figure," Ali Wyne, a former Harvard University researcher and co-author of a book on Lee, told Mic. "His figure loomed very large in Singapore's domestic and foreign policy."

What did Lee do? When most people think of Singapore, they think of a wealthy, low-tax, tropical oasis, so inviting that American billionaires renounce their citizenship to live there. But it wasn't always this way.

When the country achieved independence from Malaysia in 1965, unemployment and labor unrest were rampant, and the GNP per capita was a mere $320, according to government sources. Before Singapore developed desalinization and water reclamation techniques, they were almost totally dependent on tense agreements with Malaysia for the water they drank. Forty years ago, most Singaporean homes were simple affairs, made with thatched roofs.

Today, that seems like ancient history. Modern Singapore, with its amazing airport and pristine artificial beaches, oozes a sense of luxury and calm. Its GDP per capita, at about $55,182 in 2013, is higher than most of the world, including the United States. Its government was rated the fifth least corrupt in the world by Transparency International, ahead of regional neighbors like China and Malaysia, which were 100th and 50th respectively, as well as the United States, which ranked 23rd.

Singapore's public services are also frighteningly efficient. A World Bank report found that Singapore had "world-leading" public services obtained at a fraction of cost. For a snapshot, the country spends less than 3% of its GDP on education and less than 2% on health care, yet achieves superior outcomes than other developed countries which spend far more. The United States, for instance, spends roughly 7.3% of its GDP on education and a whopping 17.9% of its GDP on health care. Singaporeans outlive Americans by almost five years, and their students routinely trounce Americans in international tests.

Without an abundance of natural resources, the country was forced to look for higher-end industries for its economic growth, which led to the city marketing itself as a low-tax hub for foreign direct investment. It was a strategy that paid off handsomely: In 2014, total foreign direct investment in Singapore was approaching a trillion dollars. Today, Singaporeans often measure their success with the five Cs: cash, cars, credit cards, condominiums and country club membership.

This was Lee Kuan Yew's achievement.

The big lesson from Singapore: Pragmatism. Over the decades, representatives from governments around the world, most notably China, have made pilgrimage to Singapore to study its success. China's economic miracle over the last 30 years owes much to conversations between the two countries in the late 1970s. For America, the nation offers a mixed bag of broad possibilities, but is decidedly more limited when it comes to specifics.

"I think the most important insight is the value of pragmatism in policy making," Harvard researcher Wyne told Mic. "U.S. politics would benefit from a greater dose of pragmatism."

According to Wyne, Lee took a coldly unsentimental and open approach to government. If ideas worked, they were expanded, and if they failed, they were discarded. Over the course of his life, he enjoyed cordial relations and respect from Chinese communists, American capitalists and everyone in between.

"Lee Kuan Yew would always say, 'You can't govern with soundbites,'" said Wyne, who added that the statesman had bemoaned the rise of the 24-hour news cycle. He believes Lee would have detested the era of social media and hyper-partisan politics in America and considered them harmful distractions from important issues.

It's hard to know what a more pragmatic approach to American politics might look like, but one can imagine that it would not include things like the recent debt ceiling fights, which achieved nothing but a downgrade of America's credit rating. It would probably also avoid things like the 2013 government shutdown, which also achieved nothing but did manage to halt life-saving cancer research.

Further afield, with a little Lee pragmatism, one could imagine gun laws that prevented firearms in schools and bars but also protected the legitimate interests of hunters. One might also see an energy policy that sought energy security, while also not ignoring thousands of scientists warnings of global climate change.

The limits of Singapore. "Lee Kuan Yew was not a booster of Western-style democracy," said Wyne, adding that the country was largely entrusted to an undemocratic elite that ran the country on behalf of everyone else. "It's a very un-American idea," he said.

Lee's vision alone was not enough. Much of Singapore's success came from his decades-long control over decision-making. In America, ideas good or bad can languish in committee hearings. Singapore faces no similar issues. The ruling People's Action Party, which has held power since 1959, also holds 90% of the seats in the nation's parliament. Opposition parties are not crushed with guns but rather litigated into bankruptcy.

During the rush for development, human rights too had to take a backseat. Critics of government policy could face arbitrary arrest at any time. "We have to lock up people, without trial, whether they are communists, whether they are language chauvinists, whether they are religious extremists. If you don't do that, the country would be in ruins," Lee said in 1986.

Given the uniqueness of Singapore, Lee himself always cautioned other nations from attempting to emulate its model too closely. "[Lee] would say, 'I am not sure how applicable [Singapore] would be,'" said Wyne.

And rightfully so — given the specific circumstances of Singapore and Lee's expansive control of almost every aspect of its activities, it's unclear how scalable this kind of governance is. In many ways, Lee was running his own real-life SimCity, and that's not something that always translates all that well to real life.

Lee was one of the last of a generation of Asian leaders who helped lift their countries out of poverty and colonialism. If nothing else, his passing marks the end of an era, for a newly resurgent continent that in many ways he helped to create.