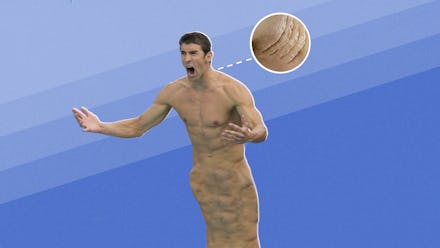

Here’s what Michael Phelps’ body would have to look like in order to beat a shark in a race

Decked out in shark fins and flippers, the swimming legend Michael Phelps tried and failed to beat a great white shark in a 100-meter race. It was a predictable ending, but it still made for great television.

The race was a high-profile stunt for Shark Week, an annual event on the Discovery Channel that reels in millions of viewers. No, the shark wasn’t real — it was a simulation of an actual shark’s speed, digitally rendered in the water next to Phelps, a 28-time Olympic medalist, who donned a wetsuit that supposedly imitated shark skin and added a tail fin for the ultimate man-versus-animal challenge.

Even with the added features, Phelps was a goner. He lost the race by two seconds.

According to an expert, Phelps barely had a chance to begin with. “I can’t think of a way [humans] could swim faster without basically being something like a shark,” Brooke Flammang, a professor at the New Jersey Institute of Technology who studies sharks, said by phone. “Even under the best circumstances, there are just too many features inherent in sharks that make them good swimmers.”

So how would the human body need to evolve to best a great white shark in a race? Let’s find out.

Phelps vs. Shark: Here’s what went down

Somehow, the Discovery Channel managed to find a guy wild enough to ride a “floating bike” — yes, pedals and all — with a decoy seal hinged on the back as a way to lure sharks along the race path.

But much to viewers’ disappointment, there was no real race alongside a great white. As one Twitter user put it, “Call me crazy, but I thought they were gonna put Phelps up against a real shark, not a simulation. I feel robbed.”

Oh, the joys of marketing. Nevertheless, the shark swam the 100 meters in 36.1 seconds; Phelps came in at 38.1 seconds. But, to be fair, he did beat a reef shark at a 50-meter simulated race, according to Vox.

Phelps vs. Shark: Why it was no contest

Phelps hardly had a chance, and it’s silly to think he could have. Humans can, at best, swim around 6 mph, according to the Verge, and that’s among the fittest — the average person swims three times slower than that. Meanwhile, great white sharks can swim at at least 25 mph.

And even with a fake tail for a boost, Phelps just doesn’t have the mobility that many sharks do.

“Their total body shape is hydrodynamically ideal,” Flammang said. In a 2011 study, she and her colleagues used a special type of imaging technique to break down the movements behind a shark’s tail. Flammang found that these tails produce twice as many jets of water than that of regular fish. Basically, a shark has the power to force its tail in both directions, creating more powerful strokes.

Basically, a shark has the power to force its tail in both directions, creating more powerful strokes.

“Sharks are different than all other fish because they have a special muscle that allows them to change the stiffness of their tail mid-beat, which allows them to give continuous thrust,” she said. ”[Other fish are] only creating a thrust when their tail first turns the other direction.”

Phelps vs. Shark: Here’s what humans would need to outswim a Great White

Believe it or not, futurists have already asked the question: Will we ever get humans to outswim sharks?

Probably not. But when asked what the human body would have to change, Flammang had two suggestions (aside from a strong tailfin): gills, and more flexible bodies.

“Gills would be the first thing. With the way gills work, they actually have about an 80 to 90% extraction efficiency of oxygen from water,” she said. “[Humans are] only getting 50 to 60% extraction of oxygen from the normal air we’re breathing. That’s important metabolically to do anything endurance and keep our muscles going.”

Because sharks draw oxygen from water, they don’t have come up to the surface for air. But even an athletic swimmer might only be able to move about three minutes underwater before taking a breath, according to Popular Science.

Humans would also need much more flexible bodies to swim like a shark, perhaps with their organs in a more centralized location. As it stands, our lower halves really only bend at the knees, hips and ankles, but “a shark has a long chain of bones, each of which can bend with their neighbor,” Flammang said.

Sharks “can curve throughout their entire body,” she said. “All their organs are crammed up in a quarter or a third of their body, toward their head … The second half of their body is nothing but muscle.”

Sharks “can curve throughout their entire body. … The second half of their body is nothing but muscle.” — Flammang

It seems that biology rigged the Shark Week race from the beginning — but it might’ve still been worth the oversell. Phelps wasn’t really in it to win: He allegedly aimed to raise awareness about shark species, some of which are endangered by trophy hunting, warming waters and acidic seas. As it stands, plenty more research has to be done to preserve shark populations for the future.

“We still don’t even know a lot about the habitats they live in, how long they live, or how many are out there,” Flammang said. “If we don’t try to get that information, all of a sudden, there will be this day where there are none of them left.”