What College Students Were Studying 40 Years Ago vs. Today

Since the 1970s, the tech sector has become an increasingly attractive career option for young people. College students with a bachelor's degree in a STEM field (science, technology, engineering, mathematics) are at a significant advantage come graduation time, receiving much higher starting salaries than their liberal arts classmates.

But apparently, American college students didn't get the memo.

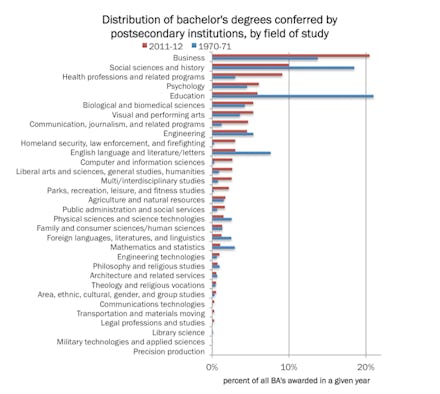

The graph below, compiled by the National Center for Education Statistics, demonstrates what percentage of college graduates majored in each field in the 1970 to '71 school year, and then the 2011 to '12 school year. And the comparison doesn't look too good for the future of America's STEM sector.

Image Credit: National Center for Education Statistics

Among the top five degrees, health professions is the only STEM major that made the cut. It's grown significantly since the '70s to cover over 9% of college graduates. But with the exception of related medical majors — psychology and biological/biomedical studies — other STEM fields are suffering.

The percentage of engineering majors declined since the '70s, while degrees in physical science dwindled down to 1.5%; a paltry 1% of graduates decided to major in mathematics and statistics. Though the percentage of graduates in computer science and IT has increased incrementally, the number remains dismally small.

Why is this so concerning? As PolicyMic previously reported, STEM fields are where jobs are being created. According to U.S. government estimates, STEM employment grew by "more than 30 percent, from 12.8 million STEM jobs in 2000 to 16.8 million in 2013."

Despite the huge potential for growth in this sector, American students seem less than inclined to pursue STEM careers. Not only have high schoolers received declining scores on related AP, PISA, SAT and ACT exams, they have also reported lower and lower interest in STEM fields.

Image Credit: U.S. News & World Report

But this isn't just a matter of Americans not filling the demand for jobs — it also has to do with America's competitiveness in the globalized job market. On international standardized test rankings, American students are doing much worse than comparable OECD countries. That's a bad sign for the future of American innovation: Young people in other countries are reporting much higher aptitude in math and science, while American students are falling behind.

At both the high school and college level, interest in STEM jobs does not match the sector's enormous potential and opportunity. While there are always people who choose a non-traditional approach to education or decide to change fields after graduating from college, figures like this help to highlight the great disparity between the future of American economy, and where the interests of today's young people actually lie.