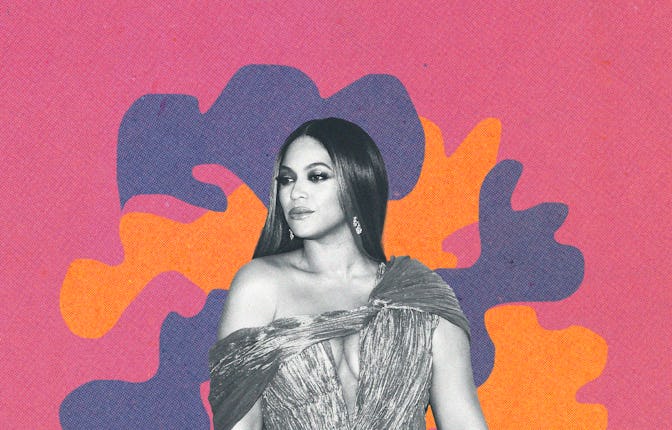

Beyoncé nearly captures the perfect club night with ‘Renaissance’

The singer’s first album in six years is frequently ecstatic, rhythmically daring, and engrossing.

The most satisfying vocal on Renaissance, the new Beyoncé album built on a sweaty reassemblage of more than a half-dozen different dance genres, is the hook on its lead single, the Robin S.-interpolating “Break My Soul.” She repeats the lyric “You won’t break my soul” four times, hitting those words, and especially the break in the middle, first with viciousness, and then something a couple of degrees gentler. In those four identical lines, buried deep in the beat’s pocket, Beyoncé encapsulates the promise of a record that pairs her with instrumentals of this kind: one of the most instantly recognizable voices in music transforming a collage of samples and found sounds, the voice itself embodying the tension and release that house, for example, relies on as lifeblood.

It’s been more than six years since the last proper Beyoncé album, Lemonade, was released as a connected series of videos on HBO. Few artists working in any medium — few people on Earth, really — have Beyoncé’s raw monocultural power, and so Lemonade was a seismic event, due in part to its revelation that her husband, Jay-Z, had been unfaithful to her; that footage of him curled, near-fetal, on a bed next to her could be overshadowed by other scenes from the project shows just how totalizing her celebrity had become. But the period between Lemonade and now has marked a creative low point. Everything Is Love, a 2018 joint album with Jay-Z, was half-formed; The Gift, the live-action Lion King reboot’s soundtrack she oversaw the following year, was texturally interesting but vocally staid, and fell victim to the trap that ensnares so much studio-commissioned songwriting, creeping toward the hyper-literal.

Renaissance is a welcome corrective: frequently ecstatic, rhythmically daring, and for the most part engrossing. With nods to bass and bounce, techno and contemporary trap, brittle Midwestern house and glitchy synthpop, Beyoncé narrows the aperture from the omnivorousness that marked 2013’s self-titled record and, with slightly diminishing, more confounding returns, Lemonade. The album does not quite replicate the feeling of a delirious night in the platonic-ideal club — the illusion is broken by a handful of lackluster writing passages, including those where she ruminates on her public persona in a way no one already dissociating would want to, and by songs like the lite-funk “Cuff It,” which sounds unwelcomely organic — but it has long stretches that are wholly immersive, and is a tantalizingly specific pivot from such a major star.

“Beyoncé goes a step further, leveraging the fine print to place her behemoth pop records in Black musical lineages that by comparison are smaller, less lucrative — even, yes, obscure.”

On the molting house cut “Alien Superstar,” Beyoncé sings, appropriately smug, that she’s a “mastermind in haute couture/Label whores can’t clock—I’m so obscure.” This is very possibly true (at least in person; one should not underestimate the power of teenagers on the internet to place and price every textile in a jpeg), but it’s the diametric opposite of her approach to crediting musical collaborators and influences. Where her husband has made a career out of subsuming other rappers’ styles as quietly as possible into his own, Beyoncé’s flaunting of ostentatious liner notes is a performance in itself, and aligns her more closely with the other titanic ex-Roc-A-Fella rap star, Kanye West. But West’s co-writers and sample clearances are seemingly foregrounded to confirm good taste alone; Beyoncé goes a step further, leveraging the fine print to place her behemoth pop records in Black musical lineages that by comparison are smaller, less lucrative — even, yes, obscure.

In the past, while these nods have the aggregate effect of bolstering the perceived depth and credibility of her work, the individual reference points have lived mostly as footnotes. But the musical forms Beyoncé contorts herself into on Renaissance, by their nature, decenter lead vocalists. By consequence, she works best here when her voice becomes part of the song’s rhythmic architecture, competing with the drums as it does about 75 seconds into the Honey Dijon-produced “Cozy,” or when she is left slightly out of focus, as on the disco odyssey “Virgo’s Groove,” where her dynamic performance seems to have been shrunken just enough to fit inside a beat that is impervious to everything but itself.

“Virgo’s Groove” is breezy, wistful, and long; it allows the album to breathe without stalling its momentum the way “Cuff It,” the sleepy Syd cowrite “Plastic Off the Sofa,” or tortured Carterpreneur bars like “I be beatin' down the block, knockin' Basquiats off the wall” are liable to. The shrewdest decision Beyoncé makes on Renaissance is to let “Virgo”’s six minutes play out, then collapse that newfound breathing room into a six-song run (the Grace Jones- and Tems-featuring “Move” through “Pure/Honey”) that is, more often than not, downright claustrophobic. This is also the stretch of the album where The-Dream’s influence is most evident; the longtime Beyoncé collaborator is credited on ten of the LP’s 16 songs, and while only three of those appear in this block, they all include his trademark economy of base desire — especially Renaissance’s crown jewel, the irresistible “Thique.”

Through genre, syntax, and overt reference, Renaissance is Beyoncé’s attempt to distill a relationship with her queer audience in a fraught period (are there any others?) for those fans. It is notable that while doing so, she curbs the habit, which had grown more prevalent throughout her records over the past decade, of writing songs that were self-consciously Political. Here she allows — requires — whatever political weight a listener might want to project onto these songs to be mapped onto the physical. In that sense, it’s fitting that she only mostly succeeds — since when is it possible to live fully in our bodies, or fully outside of them?