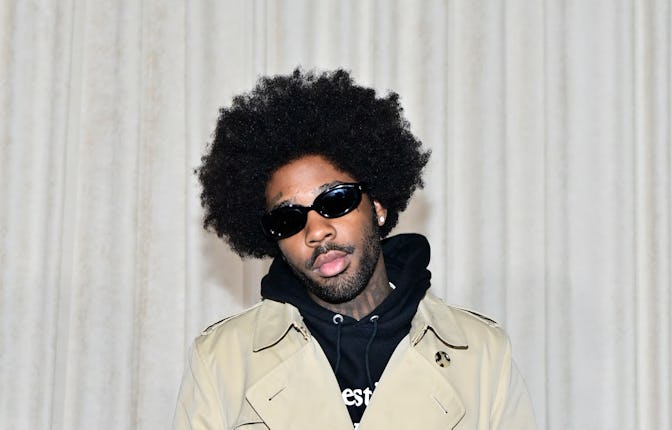

On WASTELAND, Brent Faiyaz won’t let himself off the hook

The singer/songwriter supports admittedly toxic lyrics with some of the year’s most daring musical decisions.

While the arc of Brent Faiyaz’s career traces wholesale changes in his vocal approach and taste in production, the most revealing evolution can be seen in his writing. On his two earliest, self-released mixtapes, 2012’s Sunset Avenue and the following year’s Black Child EP — a pair of records that bracket his senior year of high school — Faiyaz is essentially a rapper, floating and then barreling his way through beats, many self-produced, that attempt to fuse 40’s post-808s & Heartbreak iciness with the more structurally ambitious things happening on Soundcloud and Tumblr at the time. These verses are essentially devoid of any lyrical style: They are literal and linear, rote citations of emotional crises and careerist aspiration, almost remarkably blank.

In the near-decade since he finished those tapes, Faiyaz, still only 26, has expanded on the cool R&B suggested by a pair of standout tracks tucked toward the end of Black Child. His sprawling new album, WASTELAND, is by far his boldest effort to date: rhythmically varied, instrumentally diverse, and written with such tonal control that even the archest self-criticism can double as sincere castigation, the most gratuitous consumption as self-conscious affect. Except for a disappointingly blunt organizing device, Faiyaz leaves these threads irresolvably tangled, making WASTELAND one of the year’s most thematically dense albums as well as its most musically exciting.

Raised in Howard County, Maryland (and briefly alienated during a family move to Charlotte, North Carolina), Faiyaz popped up on the national radar in 2016, singing the hook on “Crew,” which became a major hit for GoldLink. While the headliner was severely overshadowed by his fellow D.C. native Shy Glizzy, it was that chorus that anchored a song which had been given, especially by Glizzy, a runaway momentum. Faiyaz’s vocals are so languid as to be practically taunting in the face of the rappers’ urgency.

While the effect might have been jarring to those who were just being introduced to the singer, this actually represented the logical end of an effect Faiyaz had been cultivating for years. After sounding overwhelmed at times throughout Sunset Avenue, he took a much more aggressive approach on Black Child, his rap verses pulsing and muscular. At times he overshot the mark—there are points on that mixtape when Faiyaz sounds impervious to the beat rather than simply nimble over it. And from there, there were moments of overcorrection (on the first half of the 2016 EP A.M. Paradox, and during some of the gentler moments on his 2017 full-length debut, Sonder Son) when he once again sunk back into lockstep with the music. But with time he ironed out that relationship, and WASTELAND hears him in a rolling push-pull with the production, stabs of violin strings mirrored by fragmented chorale arrangements, little dots of maximalism scattered throughout a record that is often, otherwise, stripped to the bone.

The songs here are concerned with substance abuse, the pitfalls of celebrity, and sexual appetites — nothing novel on its surface. Faiyaz brings depth to each topic through those aforementioned tonal complications. Take, for instance, the Alicia Keys-assisted “Ghetto Gatsby,” where the word “sprinter” — as in, “I got models in the sprinter” — is repeated, treated with something like reverence. When he sings, on that song’s chorus, about being dealt a bad hand in life, he could plausibly be fooling himself or knowingly holding an exasperated woman at bay. Or see “Addictions,” where the first verse (“I wanna have more threesomes but you’re so territorial”) is almost bright and bouncy enough to undercut that song’s title. And though he delivers the words with supreme poise, the chorus on “Role Model” suggests a man struggling to convince himself with his own stonewalling:

“I'll be your role model / Don't leave the house tomorrow / I gotta meet with Audemars /Tell me what you want /You say you had enough 'cause my time ain't enough /Girl, it's never enough for you / But you can wait until after tomorrow”

WASTELAND is filled with musical decisions that, rather than providing immediate shock, grow more obviously daring as they play out. The second half of “Price of Fame” is one long comedown, like the one he fears on “FYTB”; the opener “Loose Change” welcomes those violins to come reset the mood every time drums come too close to providing a real climax. And it’s fitting that “Rolling Stone,” a song that pleads for equilibrium only to find the wrong kind (“I’m rich as fuck and I ain’t nothing at the same time”), sounds like someone trying to steady himself as he wanders home, drunk beyond belief.

Threaded through the album are skits that dramatize arguments between Faiyaz and a woman — we’re to gather his ex — who’s pregnant with his child. As Faiyaz (or: his character from the songs proper) extends a trip to sleep with other people and dodge this expectant woman’s calls, she grows despondent and eventually threatens to jump from the Pacific Coast Highway to her death. It’s melodramatic (and poorly acted) in such a ghastly way as to take the listener out of the experience entirely. Worse: it makes caricaturish the dread that already runs through WASTELAND, laid there by hints and implication. This is ultimately forgivable, especially because the only song to appear after that suicide, the glistening “Angel,” fails — maybe intentionally, maybe not — to provide any meaningful catharsis. Because no matter who is watching over Faiyaz, he’s left down here with the rest of us, a thousand ids shouting over one another.